Remembering Christopher Hogwood (1941-2014) | reviews, news & interviews

Remembering Christopher Hogwood (1941-2014)

Remembering Christopher Hogwood (1941-2014)

Tributes to the conductor, scholar and gentleman from musicians who worked with him

He was not only a bracing conductor/harpsichordist pioneer in period-instrument authenticity, writes David Nice, but also a gentleman and a scholar.

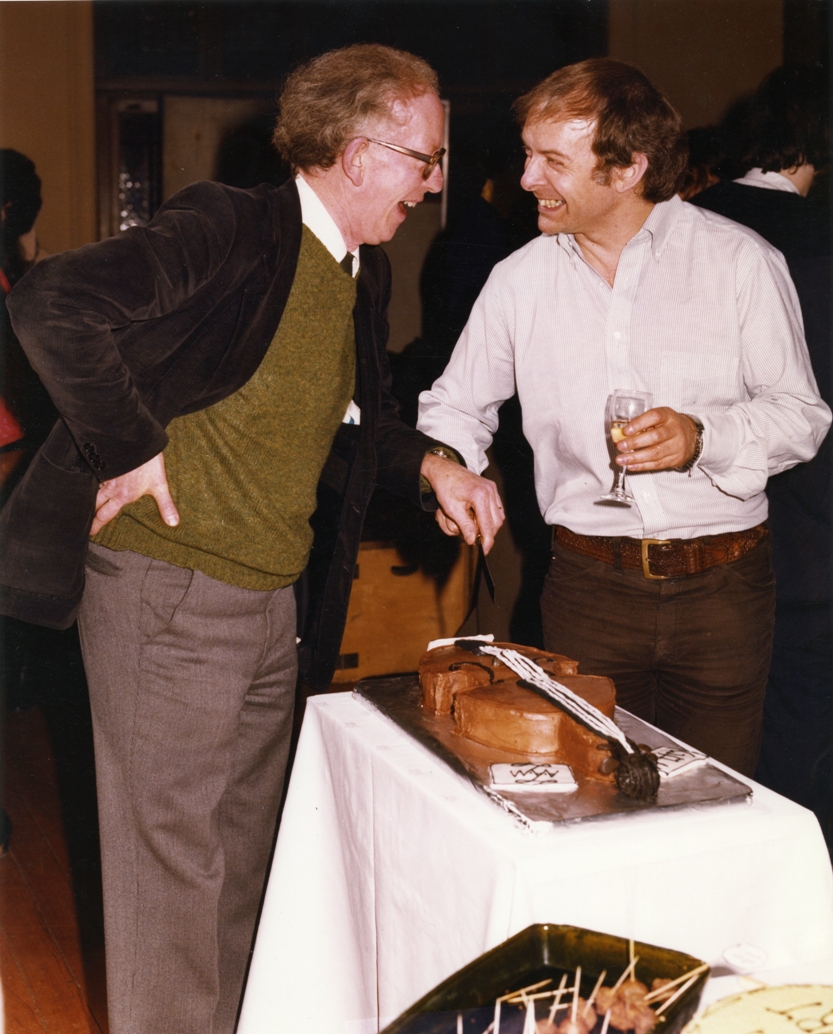

Hogwood was very much a part of my own adolescent acquaintance with the authentic-performance movement, in the promotion of which – as several of our distinguished commenters point out – he was no zealot. Yet he did make sure that scholarship went hand in glove with the excitement of live or recorded performance: the Haydn sets are beautifully documented by fellow scholars James Webster and David Wyn Jones, whose roles in the developing discoveries he was clear about crediting in the interview (pictured below: Hogwood with Jaap Schroder on completing his Mozart symphonies series in 1985, © AAM).

His was the first period-instrument performance of Handel’s Messiah I heard – the recording still sits on the shelves – and though his sphere was never my primary enthusiasm, it was a joy to discover so many of the Handel operas and “English oratorios” through him at a time when they had nothing like the popularity they enjoy now. Two still in the home collection are that revelatory Orlando and the extraordinary Athalia mentioned by Andrew Hammond below: what were the chances of hearing subsequent Dames Emma Kirkby (one of our tribute-payers below) and Joan Sutherland on the same recording, not to mention the treble of Aled Jones? theartsdesk also reviewed what would seem to have been his final major appearance with the Academy of Ancient Music he founded, last year's Barbican concert performance of Imeneo.

His was the first period-instrument performance of Handel’s Messiah I heard – the recording still sits on the shelves – and though his sphere was never my primary enthusiasm, it was a joy to discover so many of the Handel operas and “English oratorios” through him at a time when they had nothing like the popularity they enjoy now. Two still in the home collection are that revelatory Orlando and the extraordinary Athalia mentioned by Andrew Hammond below: what were the chances of hearing subsequent Dames Emma Kirkby (one of our tribute-payers below) and Joan Sutherland on the same recording, not to mention the treble of Aled Jones? theartsdesk also reviewed what would seem to have been his final major appearance with the Academy of Ancient Music he founded, last year's Barbican concert performance of Imeneo.

Our guest contributors include legends in their own right, several of them as distinguished in their multitasking as the great man himself.

PAVLO BEZNOSIUK Leader, Academy of Ancient Music

Chris was someone who delighted in musical discovery, through his research and editing relishing the minutiae of a composer's process as well as the broad strokes. It was this delight that he sought to instil in his players, never trying to “put one over” or talk down like a know-it-all but genuinely to enthuse those around him. This extended to everyone: if even the lowliest second violinist expressed an interest or puzzlement about some aspect of the work in hand (tempo, phrasing, dynamics, anything) he would engage, so keen was he for intellectual discourse and so genuinely interested in passing on knowledge.

In the rehearsal room, concert platform and recording studio (pictured left: Hogwood recording with the AAM in the 1980s, © AAM) he was always collaborative and collegial, an enabler of the musicians around him rather than an "auteur". Within a certain framework dictated by the composer's unadulterated text he pretty much let the players get on with their job while he got on with his, a no-fuss conductor whose motto, I believe - although he never articulated it as such - would have been "let the music speak for itself".

In the rehearsal room, concert platform and recording studio (pictured left: Hogwood recording with the AAM in the 1980s, © AAM) he was always collaborative and collegial, an enabler of the musicians around him rather than an "auteur". Within a certain framework dictated by the composer's unadulterated text he pretty much let the players get on with their job while he got on with his, a no-fuss conductor whose motto, I believe - although he never articulated it as such - would have been "let the music speak for itself".

He also had a sense of the showman about him and managed to combine his intellectual rigour with a charming stage personality. His spoken introductions (often off-the-cuff) were a masterclass in succinct, entertaining and inclusive public speaking.

Stand-out memories for me would include the first tour of Japan and Taiwan (the first by a period-instrument orchestra, I believe) and playing/recording Mozart piano concerti in Salzburg with Robert Levin playing Mozart's own piano.

CATHERINE BOTT Soprano and broadcaster

A few years ago I was asked to write and present a programme for BBC Radio 4 about Cecilia, patron saint of music and musicians, and the ways in which her feast-day has been celebrated in England, focusing in particular on the glorious musical creations written in her honour by Purcell and Handel. I know these pieces very well, but my job, as usual these days when making radio or TV programmes, was to “go on a journey”. Broadcasters have always had to ask questions to which we already know most if not all of the answers, but this “journey” thing, particularly in the context of my then regular Radio 3 gig presenting The Early Music Show, was beginning to niggle.

“Blessed Cecilia”, though, has been exploited, in both art and music, to manipulate our emotions: the truth about the real woman is elusive, and I certainly didn’t already know everything about her. Asked whom we should seek out to discuss the music written in Cecilia’s name, I said firmly that we needed to talk to Christopher Hogwood.

Over coffee and squares of rather divine high-cocoa-score chocolate in his Cambridge house, we recorded an informal conversation about Cecilia’s place in baroque music. Naturally, Chris was articulate and authoritative; what’s harder to convey at this distance is his quiet delight in the subject, the sense that he too was still discovering new and fascinating things, the pleasure our interest gave him. He was enviably fluent, with a rich and precise vocabulary – he’d once been one of Radio 3’s cooler presenters, remember, on The Young Idea – but he didn’t waste a word, didn’t grandstand or patronise, didn’t come over like a quaint and fusty don or a career-building telly-don. It was obvious that we were going to be able to use just about everything he said, without any need for editing.

Over coffee and squares of rather divine high-cocoa-score chocolate in his Cambridge house, we recorded an informal conversation about Cecilia’s place in baroque music. Naturally, Chris was articulate and authoritative; what’s harder to convey at this distance is his quiet delight in the subject, the sense that he too was still discovering new and fascinating things, the pleasure our interest gave him. He was enviably fluent, with a rich and precise vocabulary – he’d once been one of Radio 3’s cooler presenters, remember, on The Young Idea – but he didn’t waste a word, didn’t grandstand or patronise, didn’t come over like a quaint and fusty don or a career-building telly-don. It was obvious that we were going to be able to use just about everything he said, without any need for editing.

As we left, my producer, who had previously been intent on involving half-a-dozen talking heads in the programme (them’s the rules nowadays) simply said: “We don’t need to talk to anyone else, do we?” Well, there were some other voices in the end, but Chris’s contribution conferred real intellectual distinction on our half-hour documentary.

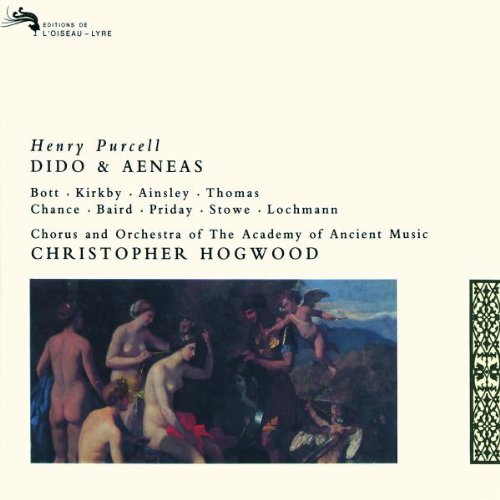

He was similarly thoughtful and wise when making music: during rehearsals for his recording of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas in 1992 (cover pictured above; listen to the complete recording overleaf), having agreed with me that the nobility of Dido’s Lament is a private, inward thing, he said very little on the session, never imposing his own will on my performance. At the time I was so accustomed to prescriptive HIPP-autocrat conductors that I didn’t fully appreciate his generosity of spirit, but as that recording is still highly regarded more than 20 years later I happily concede that he knew what he was doing.

Christopher Hogwood was a musical visionary, and generations of musicians now enjoying careers in historically informed performance owe him a great deal. But we should also be thankful that his vision was supported by scholarship of rare depth and integrity.

JAMES BOWMAN Countertenor

Chris remained constant in his views on interpretation and actual performance, and I always admired and respected him for it.

ANDREW HAMMOND Priest, singer and former arts administrator

My particular memories of Chris come from a short, specific period in the late 80's, when I was his personal assistant. In those days it was a part-time job which he would give to indigent young things who were making their way into the world of music. I was looking after his house and its contents, in essence, especially when he was away on tour.

This in itself was fascinating because Chris was a collector of beautiful things: paintings/prints, books, instruments... When I was with him he lived in a small house owned by Jesus College, Cambridge, but it was bursting at the seams. One of the first things I had to do was help buy him a new house. He was the other side of the world, so I took on the negotiations: those were the heady, mad days of a property boom, so it was a bit white-knuckle. But we got the house in Brookside, which he turned into the most elegant home for him and his collections and, of course, for his long-term companion Tony.

Chris was at the height of his powers, in the midst of his long, productive and extraordinarily successful period of recording with Decca. He was recording the Beethoven symphonies, and one of the first things he did when I started was play me the slow movement of the Eroica on his formidable “hi-fi” (as we called it then!). He talked me through it in the way that film directors sometimes do now over DVDs, if you select their commentary. We stood listening to this plangently beautiful music, beautifully played. He then lightened the mood by playing parts of Athalia, and grinningly recalling the madness of recording with the unlikely combination of Emma Kirkby, Aled Jones and Joan Sutherland.

Chris was at the height of his powers, in the midst of his long, productive and extraordinarily successful period of recording with Decca. He was recording the Beethoven symphonies, and one of the first things he did when I started was play me the slow movement of the Eroica on his formidable “hi-fi” (as we called it then!). He talked me through it in the way that film directors sometimes do now over DVDs, if you select their commentary. We stood listening to this plangently beautiful music, beautifully played. He then lightened the mood by playing parts of Athalia, and grinningly recalling the madness of recording with the unlikely combination of Emma Kirkby, Aled Jones and Joan Sutherland.

He was busy, and rightly so, but sometimes he would get back from tour or even just from a demanding day in London and would need to decompress. He would do this by going into his music room and playing: not Chopin's fortepiano, which he had, or the harpsichord, but the tiny clavichord, that private little instrument. Faintly heard, the sounds were intimate and healing.

EMMA KIRKBY Soprano

In performance Chris was always calm and genial - he spoke to audiences in the best way, full of interesting and helpful information without ever patronising or talking down to them. He was an instinctive educator: even after he had had what appeared to be some sort of stroke, which affected his short-term memory, I gather he still finished this year's Gresham lectures, with that trademark repository of facts and insights still apparently available to him.

In the early years of AAM, Chris was notoriously hard on his administrative staff - probably because being super-efficient himself he had a hard time understanding others' difficulties in that area. I like to think he mellowed on that matter as time went on.

Like many of us I was a little bit in awe of him, but grateful to be treated not just as colleague but as friend. I learnt a great deal from him, both from the positive energy which he instinctively harnessed on the platform and from his specific insights: Almirena in Rinaldo’s "Lascia ch'io pianga", for instance, has a sumptuous, sad piece to sing, but also she needs an element of calculation - as Chris put it: " if she mourns prettily enough", maybe she can charm Alcina's guard into letting her escape. I remember a St John Passion at the Barbican: during the rehearsal some of us were restive, feeling everything was somehow routine and tedious - but then in the evening everyone was taken aback by the simple power and veracity of the performance. I noticed him achieving that with modern orchestras, too, in an un-maestrolike manner somehow galvanising them to give a special directness to the music.

He loved words, which endeared him to me from the start. When I shared some chamber concerts with him (Anna Magdalena songs, Purcell or whatever) he would ask me to speak to the audience, or read them a lyric, because he wanted to demonstrate how close a singing voice could remain to a speaking one.

I think his earliest instrumental colleagues were shocked and rather unforgiving when he started to do more conducting; this was partly because they did not want to lose him as a continuo colleague. Quite late on, I recorded Bach's Wedding Cantatas, with a lovely group of vintage AAM players, who were clearly delighted to have him back in the midst of them.

I think his earliest instrumental colleagues were shocked and rather unforgiving when he started to do more conducting; this was partly because they did not want to lose him as a continuo colleague. Quite late on, I recorded Bach's Wedding Cantatas, with a lovely group of vintage AAM players, who were clearly delighted to have him back in the midst of them.

Others have talked of his conducting style - I like Ernest Fleischmann's description of that among recent obituaries. I theorised that some chamber orchestras, under pressure from promoters to hire big-name conductors, found Chris a perfect solution, someone who would give them new ideas, whether in adventurous repertoire or revisiting the Baroque and Classical warhorses, but then use the lightest touch on the podium. So the musicians - in his energising presence but not required to hang on his every gesture - could find their own collective response to the scores and keep that "chamber" character in their music-making.

In our increasingly crowded world of historical performance, and in the musical world beyond, Chris remained a one-off who will be greatly missed.

MARSHALL MARCUS CEO, European Union Youth Orchestra and violinist

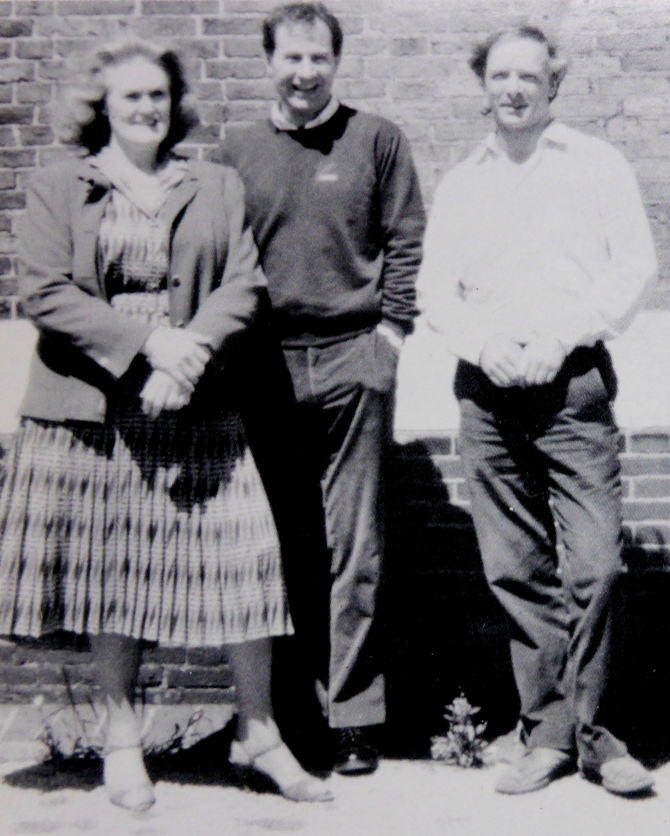

Editor, writer, researcher, instrumentalist, conductor, debater … the list could go on, for in an age of shrivelled specialists, Chris Hogwood was indeed the complete musician. Whilst many conductors were still being encouraged to behave like over indulged diva children, Chris rarely failed to treat colleagues with respect, friendship and generosity (pictured below: Hogwood by Clive Barda at the Athalia sessions, where Marcus was among the first violins).

Armed with a ferociously broad yet happily disinterested knowledge of both texts and traditions, he was superb at the apposite placing of pins into the overinflated balloon of post classical rhetoric, savouring newly rescued views on to the past with an adroitness seldom bettered by his peers in the UK.

Armed with a ferociously broad yet happily disinterested knowledge of both texts and traditions, he was superb at the apposite placing of pins into the overinflated balloon of post classical rhetoric, savouring newly rescued views on to the past with an adroitness seldom bettered by his peers in the UK.

The results may occasionally have lacked the ultimate level of polish, yet he was an expert in the art of recording, and whether in the studio or the concert hall, he never let the demands of the market submerge the search for authenticity and honestly informed music making. To work with the Academy of Ancient Music in the 80’s and 90’s, as I did, was a pleasure. Indeed generations of young musicians have much to thank him for, considering the huge opportunities and experiences that he opened up. A complete musician, but also a complete gentleman musician.

Overleaf: listen to Hogwood's recordings of Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, Handel's Athalia and Haydn's Symphony No 31

The classic recording of Purcell's Dido and Aeneas referred to in Catherine Bott's tribute

Hogwood's complete recording of Handel's Athalia with a fascinatingly mixed-bag cast: Joan Sutherland, Emma Kirkby, James Bowman, Anthony Rolfe-Johnson, Aled Jones and David Thomas

Haydn's Symphony No. 31 in D major ('Hornsignal'), the best ever argument for period-instrument horns

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment