10 Questions for Conductor Alan Gilbert | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Conductor Alan Gilbert

10 Questions for Conductor Alan Gilbert

The New York Philharmonic's music director on recording a Nielsen cycle for 150th anniversary year

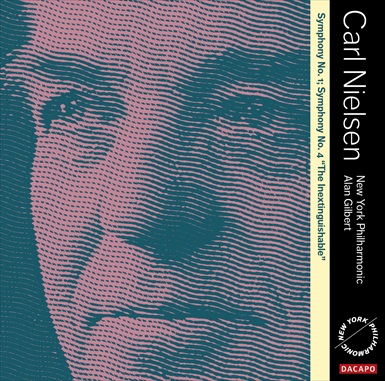

When Alan Gilbert’s Nielsen Project with the New York Phil and Danish label Dacapo is completed next year, it will total four CDs including the six symphonies, three concertos (flute, violin, clarinet) and two bonus overtures. The latest instalment (Symphonies 1 and 4) has just been released, while earlier this month the orchestra performed the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies and Maskarade Overture in three concerts which were recorded for release in January 2015.

KIMON DALTAS: Were you pleased with how the concert went? A programme like that, where everything is new or at least relatively new to the orchestra, must be a challenge. Presumably some of the musicians have never played those pieces before.

ALAN GILBERT: Certainly, nobody as far as I know had played the Sixth before. The Maskarade Overture we did in the summer, with the idea that it would be nice to have played at least one of the pieces, and of course it was a good piece to play in the parks and in Vail [the music festival in Colorado]. It’s a wonderful, joyous, raucous overture. The Fifth Symphony was done 11 or 12 years ago, so some of the musicians had played it, but they might as well never have don so, having to relearn those passages and put it together. I was really proud of the orchestra. I don’t think any other orchestra could do all those pieces – new pieces, essentially – in one programme and pull it off with such flair and command. It was really hard, I mean, some of them have told me they’ve been practising since August, because there’s no apparent rhyme or reason to some of those passages. But I think his music tells such a story, and I thought we really were able to get into the narrative. I thought they played really, really great.

I remember a performance that Herbert Blomstedt did that just blew me away

To do a programme like that, is it a risk in terms of audiences in New York? Or do you find they are embracing it?

Yeah, I was pretty pleased. I think that, you know, it’s relatively unknown music, that’s what we’re trying to address. That’s one of the reasons I guess you could say I’m championing the music, because I totally believe in it. I think it’s quirky, it’s odd. There are elements that remind me of other, slightly iconoclastic composers like Charles Ives, Janáček, Martinů – these composers that don’t quite fit into a mould, but are also very connected to the mainstream, in a way. My brief, sort of unplanned remarks at the beginning of the concert hopefully alluded to that: there’s a kind of apparently random sequence of events occasionally in his music, but I think it’s so sincere and it’s so true to life. Something will be going along, and then another element will intrude and force you to deal with an external force, and when opposing elements come into contact there’s conflict, and somehow it has to play itself out and resolve one way or another.

And there’s a bit of chaos in the middle.

There’s chaos in the middle, until one or the other sides prevails, and I think basically he’s an optimistic composer – he is, anyway, a hopeful composer – so, to put it kind of simplistically, I think he wants good to prevail, but you can tell that he was dealing with the aftermath of World War One and felt the threat of evil very strongly, and the bleakness of the opening of the Fifth Symphony that comes to a warm, hopeful place, but not secure, is very real. That’s where he was, that’s what he felt about life, and the disruptive snare drum that plays in a different tempo and is obviously trying to obliterate the good side, ultimately is vanquished, but even at the end there are hints that it’s still lurking in the background. To me it’s very real and very contemporary in a way, it’s sort of where we are today. I think his music really is... I think it’s genius, actually.

When did your love for Nielsen first begin?

I first got to know Nielsen's music a long time ago. And when I say got to know, I just mean hearing it for the first time. It was actually the New York Philharmonic playing the Fourth Symphony, I remember a performance that Herbert Blomstedt did that just blew me away. I was stunned, I’d never heard it before, I’d never imagined that such a thing could exist, and he had such a wonderful way with his music. It’s gorgeous. And then it happened that when I was conducting a student orchestra at Harvard, one of our really stand-out players was a clarinettist and we wanted him to play a concerto and he chose the Nielsen. That also was kind of a revelatory experience. Then I got to Sweden [as music director of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic], where Danish music is totally standard fare, and it happens that my artistic administrator there, Mats Engström, who is producing our recordings now, is a Nielsen expert – actually it’s fair to say fanatic. So he really got me interested, and he’s a very persuasive personality!

I realise it’s difficult to pin down a composer’s style, perhaps especially a composer like Nielsen, but I was wondering whether you could think of an example of a Nielsenism. Something that’s kind of unique to him, a touch where you’ve thought, “No one else would do that”.

I would say the juxtaposition of disparate, contrasting... I mean, they’re more than just contrasting. They’re conflicting elements. That’s very common. And there’s often – like the trombone in the flute concerto, the snare drum in the clarinet concerto, the snare drum in the fifth symphony – there’s an irritant that he inserts into the proceedings that somehow affects the flow. That’s very Nielsen. So he lays out areas that ultimately have to come together, either by really coming together, or by one defeating the other. It’s very much like a walk through life, I think. That’s a little bit how his structure is created. It is unpredictable, and it seems random, but there’s a kind of truth to it, I feel, that you really don’t know what’s coming up next in life, and you may suddenly have a person who forces you to reconsider things, and I think if you allow yourself to be drawn in and just accept the unfolding of his music, that you actually end up in a very human place.

In terms of the actual recording project with Dacapo, I get the impression that it started off as a smaller project and gradually expanded to be a complete cycle.

We actually started talking about the symphonies first and then decided to do the concertos as well, and I even got them to throw in the two overtures because it just seemed worth it to have some more music. The idea first came early on, when I became music director. I wanted to start doing Nielsen symphonies, because I remembered that Fourth Symphony performance that I heard, and I happened to think – and I still think – that the orchestra has a quintessentially Nielsenesque sound, whatever that means. I mean the kind of clarity and the power and precision and the warmth that they can bring to the soaring, singing melodies is, I think, really gorgeous. And it was a kind of fortuitous confluence. It happened that Dacapo was interested in me and the orchestra and, of course, as a Danish company they were interested in Nielsen and things came together in a sort of lucky way and the idea of this sort of panoramic project was hatched.

We actually started talking about the symphonies first and then decided to do the concertos as well, and I even got them to throw in the two overtures because it just seemed worth it to have some more music. The idea first came early on, when I became music director. I wanted to start doing Nielsen symphonies, because I remembered that Fourth Symphony performance that I heard, and I happened to think – and I still think – that the orchestra has a quintessentially Nielsenesque sound, whatever that means. I mean the kind of clarity and the power and precision and the warmth that they can bring to the soaring, singing melodies is, I think, really gorgeous. And it was a kind of fortuitous confluence. It happened that Dacapo was interested in me and the orchestra and, of course, as a Danish company they were interested in Nielsen and things came together in a sort of lucky way and the idea of this sort of panoramic project was hatched.

And I suppose the anniversary seals it.

Yeah, it gave us a nice goal and it put pressure on us to actually schedule so that we would be able to have the set ready for the anniversary. Of course, we were very mindful of these recordings that Lenny Bernstein made with Julius Baker and Stanley Drucker (pictured above), these iconic recordings of the concertos, and it’s kind of nice to bookend that with our current principals recording the concertos.

With a composer like Nielsen where there aren’t that many interpretations out there, is it harder for you to put them out of your mind? The Leonard Bernstein ones with the New York Phil for instance?

You know, I haven’t listened to Leonard Bernstein’s recordings.

On purpose?

I don’t listen to recordings really, actually. So in a sense, the presence or absence of recordings makes very little difference to me. In fact, Mats [Engström] is, I think, frustrated with me because he wanted to steer me in a certain direction. He gave me some recordings – old Danish recordings – of interpretations that he says, “That’s really the true Nielsen spirit, you should go listen to that”… and I didn’t. That’s just how I try to learn music. I try to look at the score. So I actually don’t know. I mean, except for, I guess in my distant memory, the Blomstedt performance I saw, I haven’t seen or heard that many other people’s take on these pieces, so I guess any blame or credit is squarely on my shoulders!

In terms of the recording industry itself, a project like this – a big, new recordings boxset – doesn’t come up that often. Do you see it as an opportunity to make a mark in a sense? Does that have a particular appeal to you, or is it more that you just want to conduct the music and don’t worry too much about legacy?

Recording has changed, yeah. It’s a very different scene. People used to record anything and everything, and I think you have to be much more selective these days. My feeling about recordings is pretty complex, actually. It’s evolved since I’ve been in positions with orchestras. For a long time – it was probably a youthful kind of thing – but I thought, “You know what? I don’t want to make recordings. I don’t care. Who needs my interpretations? There are already enough recordings and why should I put on record something that I’ll probably change my mind about?” And I still have a little bit of that, but I see the utility, if you will, of doing something that is kind of a benchmark of establishment success. And, frankly, I do get interested in old recordings of great performers, so when I listen to recordings it’s not so much for the repertoire, but for who’s playing. And I don’t for one second presume that my recordings will be interesting to people in the future because of who’s playing them, but I actually understand, I guess, the importance of having a record, just in case something might end up being interesting.

Recording has changed, yeah. It’s a very different scene. People used to record anything and everything, and I think you have to be much more selective these days. My feeling about recordings is pretty complex, actually. It’s evolved since I’ve been in positions with orchestras. For a long time – it was probably a youthful kind of thing – but I thought, “You know what? I don’t want to make recordings. I don’t care. Who needs my interpretations? There are already enough recordings and why should I put on record something that I’ll probably change my mind about?” And I still have a little bit of that, but I see the utility, if you will, of doing something that is kind of a benchmark of establishment success. And, frankly, I do get interested in old recordings of great performers, so when I listen to recordings it’s not so much for the repertoire, but for who’s playing. And I don’t for one second presume that my recordings will be interesting to people in the future because of who’s playing them, but I actually understand, I guess, the importance of having a record, just in case something might end up being interesting.

What is the life of these symphonies in the story of the New York Phil going forward, do you think? Are you hoping to keep them in the repertoire?

Absolutely. In fact, we’ve been specifically talking about that right now. We’re doing a lot of planning for next season and the following season and we absolutely intend to keep playing them. I mean that’s the whole point. It would be a kind of empty gesture if we just did these recordings and that would be that. The point is that I think these works deserve to be in the rotation of standard repertoire, and hopefully the public will agree.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment