First the good news. At 73, is Plácido Domingo anywhere near retiring? Er, no. When the question came up in an interview on Sunday (on video below), he answered : "The reason I don't retire is because I can still sing." And then with a glint in his eye: "I still feel I have to know the the right moment. Not to sing one day more.... nor one day less."

And more good news: Domingo does give an affecting performance as Francesco, the aged Doge of Venice in I Due Foscari, in a rather staid and conservative globe-trotting production of Verdi's early opera, which has also also been seen in Los Angeles, Valencia and Vienna. Domingo's character is tragically trapped virtually throughout the piece by the civic duty to stand back, as political machinations encircle him, and condemn his son to exile and death.

It is a role without the light of hope. Just as Verdi himself in the years before 1840 had lost two children in their infancy, and his first wife Margherita Barezzi had also died, in I Due Foscari there are frequent, poignant mentions of the fact that his son Jacopo has been the only one to survive out of four sons. The opera is Verdi's eighth, from 1844, to an original text by Byron heavily adapted by librettist Piave.

It is a privilege to see what a consummate singing actor can bring to this role. For the time he is on stage - less than a quarter of the opera - he holds it completely. There were some particularly fine moments on the first night. In his Act 1 duet with daughter-in-law Lucrezia (Maria Agresta) he was flinching, recoiling, letting his movements do the talking as she berated him for his failure to assert justice. The moment, later on, when Francesco Foscari cradled his son -Jacopo in his arms in the duet "Nel tuo paterno amplesso" was very touching indeed, as was the final scene in which Francesco Foscari is forced to resign as Doge, and then dies.

It is a privilege to see what a consummate singing actor can bring to this role. For the time he is on stage - less than a quarter of the opera - he holds it completely. There were some particularly fine moments on the first night. In his Act 1 duet with daughter-in-law Lucrezia (Maria Agresta) he was flinching, recoiling, letting his movements do the talking as she berated him for his failure to assert justice. The moment, later on, when Francesco Foscari cradled his son -Jacopo in his arms in the duet "Nel tuo paterno amplesso" was very touching indeed, as was the final scene in which Francesco Foscari is forced to resign as Doge, and then dies.

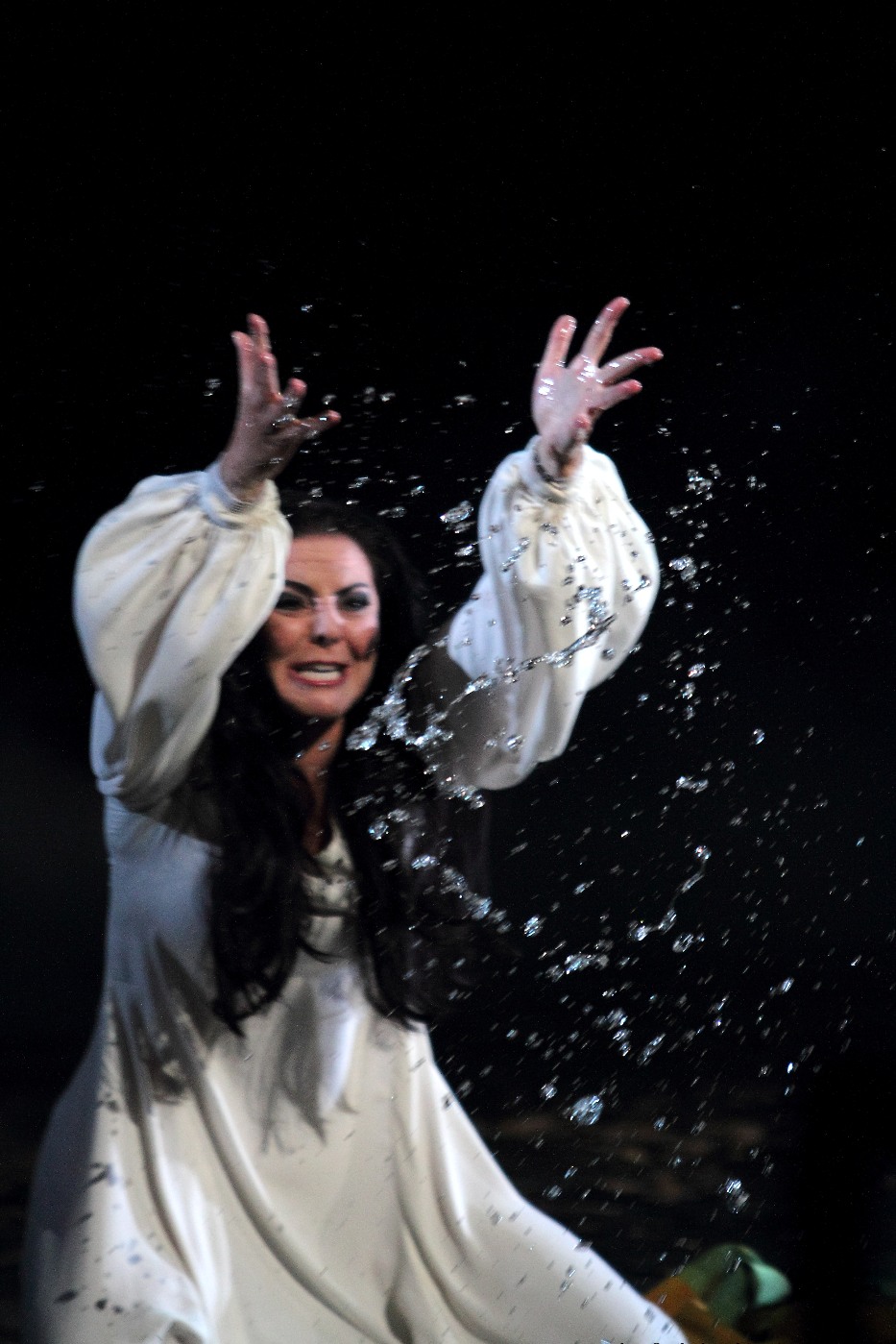

The two other principals turned in strong performances too, particularly Genovese tenor Francesco Meli as Jacopo (pictured right) with a glorious, heroic, authentic Italianate tenor sound, and strong stage presence. Lucrezia, sung by Maria Agresta (pictured below), has a tricky role, butting in to the action to protest that something needs to be done, and never getting her way. She was at her best in the quieter moments, when her melismas flowed naturally and quiter beautifully. Her louder passages sometimes sounded forced, pitch got variable, but that could easily have been first night nerves.

In the pit, Antonio Pappano made the case for the score right from the very first notes, with snarling, evil brass sounds. His tempi and his rubato in Verdi always seem to breathe completely naturally. The number of ways that the lower strings and bassooons give rhythmic impulse by pushing a broad first beat, giving wonderful support to the singers is a magical thing. Principal clarinet John Payne was the pick of the solo players.

But it is also in the score where the problems begin. It has its moments, but also its longueurs. Whereas in later Verdi, the music invariably underpins every flickering emotion and deepens the action, in Foscari there always seems to be an incongruous tum-ti-tum allegro, defying the unremittingly bleak drama, lurking somewhere just a few bars away. And then there is the fact that the situation of the three principals scarcely changes. In one bizarre sequence in the third act, plot elements are coming in thick and fast. The news arrives that Jacopo can be irrefutably proved to be innocent. The bringer of that update exits, and another immediately enters - to say he has died anyway. Yes, stuff happens, but Foscari is an opera where the condition the characters find themselves becomes their essence. They are trapped, and remain so. An opera featuring a prisoner deep underground prompts involuntary memories of Fidelio or Salome, operas in which the plots and the scores have the kind of ineluctable forward momentum almost completely absent from Foscari.

But it is also in the score where the problems begin. It has its moments, but also its longueurs. Whereas in later Verdi, the music invariably underpins every flickering emotion and deepens the action, in Foscari there always seems to be an incongruous tum-ti-tum allegro, defying the unremittingly bleak drama, lurking somewhere just a few bars away. And then there is the fact that the situation of the three principals scarcely changes. In one bizarre sequence in the third act, plot elements are coming in thick and fast. The news arrives that Jacopo can be irrefutably proved to be innocent. The bringer of that update exits, and another immediately enters - to say he has died anyway. Yes, stuff happens, but Foscari is an opera where the condition the characters find themselves becomes their essence. They are trapped, and remain so. An opera featuring a prisoner deep underground prompts involuntary memories of Fidelio or Salome, operas in which the plots and the scores have the kind of ineluctable forward momentum almost completely absent from Foscari.

The production, by American Thaddeus Strassberger, with costumes by Mattie Ullrich and stage design by Kevin Knight, setting the action in the historical period of the 15th century, does try to explain the situation, for example by placing explanatory text on a screen in front of the stage. It worked well with words from Byron at the end: "Ye have no right to reproach my length of days, since every hour has been the country's", but I found it an irritant during the Overture. There is also a desire to deal with the bleakness of the plot by attempts to distract and divert, most notably with a carnival and fire-eaters. Did such episodes keep up the energy level? Not really.

Foscari is a tricky piece to bring off, and this production does not make a particularly strong case for it. Nevertheless Domingo - the raison d'etre for it being staged - seems to be anything but a spent force. After medical scares in 2010 and 2013,is he slowing down? Far from it. This won't be his last role in London this season: he'll be back at Covent Garden, a fixture in his life since 1971, as Giorgio Germont in La traviata. He is also in the process of adding a further three baritone roles to his repertoire: Macbeth (Berlin), Don Carlo in Ernani (The Met) and Gianni Schicchi (Madrid).

- The performance on 27 October will be transmitted to cinema

- Further performances of I Due Foscari at the Royal Opera until 2 November

Next page: watch Domingo in conversation about Verdi at the Royal Opera before the premiere

Domingo interviewed about I Due Foscari

Add comment