Bolshoi Ballet acid attack leader loses his job | reviews, news & interviews

Bolshoi Ballet acid attack leader loses his job

Bolshoi Ballet acid attack leader loses his job

Sergei Filin's contract will not be renewed, and his post abolished

Sergei Filin, the Bolshoi Ballet artistic director whose sight was maimed two years ago by an acid attack organized by a disgruntled dancer, will lose his job when his contract expires next spring. Bolshoi Theatre chief Vladimir Urin announced yesterday in Moscow that he is abolishing Filin’s position and replacing it with a more management-focused director, indicating that artistic decision-making is to be taken "jointly" with the theatre directorate.

The new director will be named and introduced in September when the company returns from their summer break. Urin refused to give a name, but it does appear from his choice of pronouns to be a man.

The theatre chief said the change is due to "matters concerning the theatre's internal life", but insisted that Filin’s authority and stamp on the next season will remain unquestioned, with the last of his scheduled commissioned premieres being Ondine by Vyacheslav Samodurov (an admired former Royal Ballet principal who began his choreographic development in Britain) and a work by Dutch contemporary choreographers Paul Lightfoot (ex Royal Ballet School) and Sol Leon.

Filin, 44, will also apparently figure in the Bolshoi’s tour to London next summer, and Urin said discussions are going on about retaining him in the capacity of a "specialist" with the Bolshoi Ballet.

While it has been much rumoured that there is bad blood between the two men ever since they worked together at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theatre (Urin appointed Filin as ballet chief in 2008, but in 2011 Filin jumped ship to the Bolshoi top job), Urin’s statements yesterday acknowledge that Filin’s artistic legacy at the Bolshoi in just five years has been praiseworthy. This month the latest of his stream of commissioned creations, A Hero of Our Time, based on Lermontov’s novel, directed by the news-making theatre and film director Kirill Serebrennikov, choreographed by Yuri Possokhov (of San Francisco Ballet), has had largely positive reviews - not least for its phalanx of wheelchair-bound dancers (pictured above, © Damir Yusupov/Bolshoi Theatre).

While it has been much rumoured that there is bad blood between the two men ever since they worked together at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theatre (Urin appointed Filin as ballet chief in 2008, but in 2011 Filin jumped ship to the Bolshoi top job), Urin’s statements yesterday acknowledge that Filin’s artistic legacy at the Bolshoi in just five years has been praiseworthy. This month the latest of his stream of commissioned creations, A Hero of Our Time, based on Lermontov’s novel, directed by the news-making theatre and film director Kirill Serebrennikov, choreographed by Yuri Possokhov (of San Francisco Ballet), has had largely positive reviews - not least for its phalanx of wheelchair-bound dancers (pictured above, © Damir Yusupov/Bolshoi Theatre).

Urin hailed the quantity of fine dancers and productions that have emerged from Filin’s artistic directorship, which begs the question whether by removing the chance for his successor to exercise such creative authority, the joint directorate being proposed can emulate (or even wants to emulate) this sort of approach. While there might be several reasons for Filin's departure, abolishing his post and replacing it with more of an administrator when the chief executive acknowledges Filin’s creative legacy is an obscure answer to an even more obscure question.

However, Urin, who soon after the acid attack was brought in to replace the long-standing general director Anatoly Iksanov, has already made several rearrangements to the theatre’s tentacular management, concentrating more control in his office. He removed a prominent opera planning chief, expressing the change in similar terms to those he addressed Filin’s situation with - that the job was now redundant, yet a few months later he appointed his wife (a distinguished opera planner herself) to a rather similar job to the one he had declared redundant.

Filin, already vulnerable once he had been physically attacked, was much weakened by the volley of criticism

The command changes made to both the Bolshoi Ballet and Opera reflect the fact that the massive Bolshoi flagship, with 3,000 employees, and with special state obligations, is not easily equated to other world equivalents where creative vision comes first. Urin confessed in an interview last January with a Moscow correspondent that he faced tensions between his theatre and the government, as well as those between the theatre's ambitions and the nature of its audience. He also said that a theatre with a roll that size was "practically uncontrollable".

Filin’s status, already vulnerable once he had been physically attacked and rendered unable to do his job, was much weakened by the volley of criticism emerging from his opponents' camp during the next months. Prior to the attack, he had complained of email hacking and menacing tactics, and the dancers’ trade union defiantly elected as their leader the very man accused of assaulting him.

In his initial absences for emergency eye treatment after the acid attack in January 2013, an "artistic council" of ballet leaders, teachers and performers was installed at the Bolshoi to run daily affairs, which became the focus of power struggles and was observed to make it harder on Filin’s return for him to resume his former authority unrestrained.

During the trial of the dancer who commissioned the attack, Pavel Dmitrichenko (pictured left during the trial), allegations were made of Filin operating a casting couch with ballerinas and of manipulating company funds to favour certain performers. The allegations were wholly denied by Filin and his reputation defended by an impressive file of top dancers, but his personal standing has not recovered. It was also visible that at a time of volatile geopolitics and a sharp uprise in recent years of vocal nationalism, Filin’s internationalist artistic outlook on the Bolshoi Ballet’s repertoire incited opposition from a growing band of conservative foes within the ballet establishment.

During the trial of the dancer who commissioned the attack, Pavel Dmitrichenko (pictured left during the trial), allegations were made of Filin operating a casting couch with ballerinas and of manipulating company funds to favour certain performers. The allegations were wholly denied by Filin and his reputation defended by an impressive file of top dancers, but his personal standing has not recovered. It was also visible that at a time of volatile geopolitics and a sharp uprise in recent years of vocal nationalism, Filin’s internationalist artistic outlook on the Bolshoi Ballet’s repertoire incited opposition from a growing band of conservative foes within the ballet establishment.

The argument about how to develop Russia’s own choreographers has been heavily loaded with emotive stances portrayed as pro-West or pro-Russia from as far back as the 1990s.

Yet the remarkable thing has been how despite all that was ranged against him, Filin has continued to drive through an artistic refreshment with a rejuvenating spirit that would be hard for any world ballet company to match.

It’s a pity that the West sees little of this, given the demands of the international box office for classics from the Russians - yet Filin’s leadership (encouraged by Iksanov) continued the refreshment that his former boss Alexei Ratmansky had begun in the 2000s.

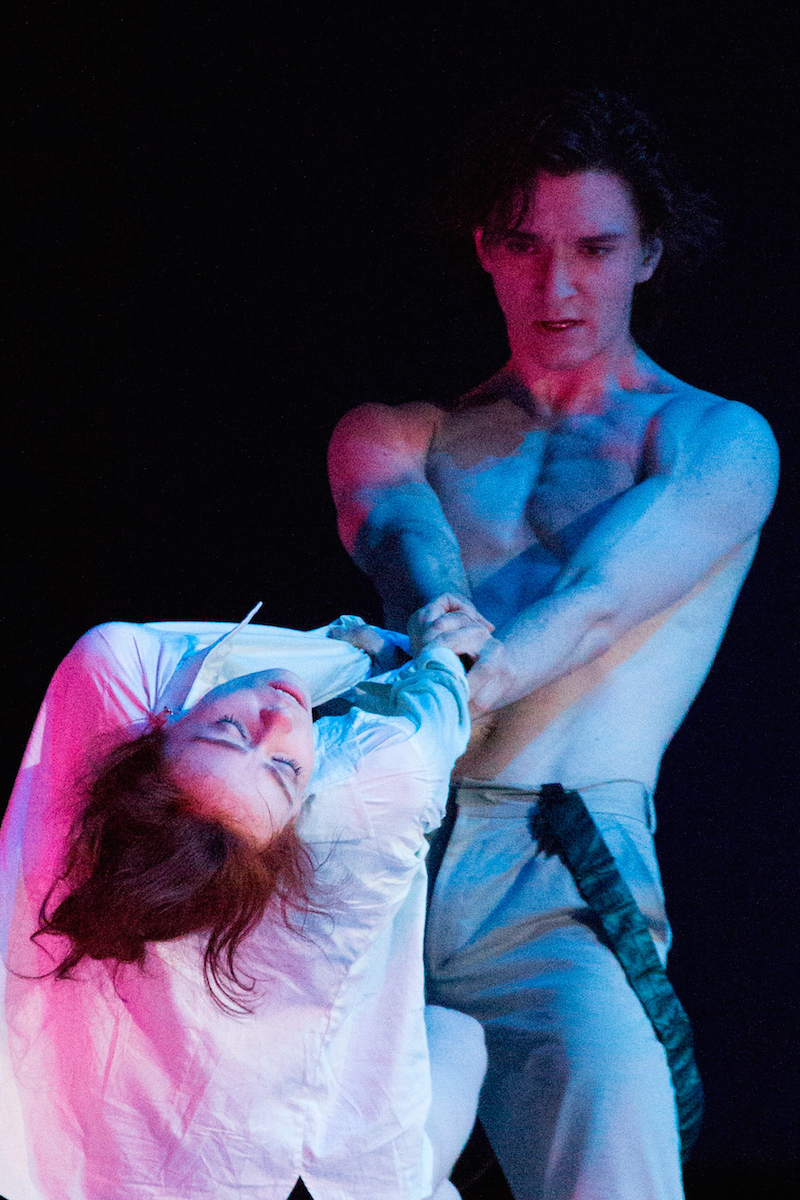

World premieres on Filin’s watch have included Ratmansky’s Lost Illusions (2011), Possokhov’s Classical Symphony (2012), Yuri Smekalov’s children’s ballet Moidodyr (2012), Pierre LAcotte's Marco Spada (2013) Jean-Christophe Maillot’s The Taming of the Shrew (2014, pictured right, Vladislav Lantratov and Ekaterina Krysanova, © Mikhail Logvinov) and Hamlet by Cheek by Jowl’s Declan Donnellan and Radu Poklitaru (2015).

World premieres on Filin’s watch have included Ratmansky’s Lost Illusions (2011), Possokhov’s Classical Symphony (2012), Yuri Smekalov’s children’s ballet Moidodyr (2012), Pierre LAcotte's Marco Spada (2013) Jean-Christophe Maillot’s The Taming of the Shrew (2014, pictured right, Vladislav Lantratov and Ekaterina Krysanova, © Mikhail Logvinov) and Hamlet by Cheek by Jowl’s Declan Donnellan and Radu Poklitaru (2015).

Filin acquired for the Bolshoi John Cranko’s Onegin (2013), Mats Ek’s Apartment (2013) and John Neumeier’s The Lady of the Camellias (2014), and Yuri Grigorovich mounted an eyewateringly opulent new production of The Sleeping Beauty for the reopening of the restored Bolshoi Theatre.

One that got away, in the immediate aftermath of the acid attack, was a hoped-for new Rite of Spring from Wayne McGregor, replaced at hair-raisingly short notice (after McGregor dropped out in alarm) by one from a Russian contemporary choreographer - a woman for once, Tatiana Baganova.

Filin's final premieres will be (in March 2016) a modern choreography triple bill of Hans Van Manen, Lightfoot and Leon and Jiri Kylian, and (in June) the new Ondine, to the Henze score written for Frederick Ashton, by the fast-rising Samodurov (presently artistic director of Ekaterinburg Ballet).

A rapid change in top brass followed the attack on Filin, bringing - along with a very painful and difficult overhaul of internal worker discipline and rules - a new insistence, at least in public, on reducing the influx of Western creatives and generating native Russian talents. Filin’s inclusion in his commissions of successful Russian choreographers based or trained abroad, like Yuri Possokhov and Vyacheslav Samodurov, has managed to look both ways.

Despite the brevity of Sergei Filin’s tenure, five years is good going for the modern-day Bolshoi Ballet, where no director for the past 20 years has survived more than that. Since the ballet chief Yuri Grigorovich was made to resign in 1995 after 32 years in post, he has had six successors - Vladimir Vasiliev, Alexei Fadeyechev, Boris Akimov, Alexei Ratmansky, Yuri Burlaka and Sergei Filin.

Grigorovich remains a fixture at the Bolshoi, at 88, either a remnant of Soviet stagnation or a monument to Soviet superiority, according to who is talking. His productions of the classical ballets still dominate the repertoire, and in today’s conservative times, with the heavy politicisation of culture going on just now, it is perfectly logical that Urin apparently already had the next director’s selection done and dusted, behind closed doors. The Bolshoi has always been the Russian government’s most important cultural flagship and its leaders are appointed by the Culture Minister, so Filin’s successor will likely conform to present government requirements.

It might also be reasonably expected that the sheer mass of new work brought in by Filin since 2011 will need to bed down with the Bolshoi audience and its patrons for a while, and that what will ensue is a period of consolidation under an efficient manager, whose priorities will be to get the notorious problems of day-to-day working conditions and casting under better control. Filin’s man management does not appear to have been one of his strengths.

Filin recently said his sight has improved to the point where he can now drive a car

Still, the Bolshoi Theatre does appear to have been an exemplary employer in regard to Filin’s injuries, funding his state-of-the-art treatment in Germany (which apparently now tallies some 30-plus operations, and is still ongoing) in the teeth of attempts at one point by supporters of his attackers to blame the German doctors for the impaired state of his vision.

Filin recently gave an interview that his sight has improved to the point where he can now drive a car. It suggests that he is now able to work relatively normally, a welcome development from the position at the trial, when Dmitrichenko was convicted of grievous bodily harm because of the severe reduction in Filin's vision to just one impaired eye. Evidently, he does not intend to accuse the Bolshoi Theatre of getting rid of a handicapped employee whose injuries were caused in connection to his employment. He told the press yesterday he had nothing to complain about in the non-renewal of his contract - "it's fair".

One extra comment by Urin yesterday carried wind of the bad old Bolshoi still lurking in the shadows. Despite the news which effectively makes Filin a lame-duck leader, he “wanted to clarify that for virtually the whole upcoming season the ballet company will be led by Sergei Filin, whose instructions must be strictly fulfilled by the company.” In a well-run and self-disciplined organization, that “clarification” should not be necessary.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Comments

The correct spelling of his

The premiere of "Lost