Soup Cans and Superstars, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Soup Cans and Superstars, BBC Four

Soup Cans and Superstars, BBC Four

Panorama of Pop art from Alastair Sooke ahead of the Tate Modern show

Pop went the easel, and more, as we were offered a worldwide tour – New York, LA, London, Paris, Shanghai – of the art phenomenon of the past 50 years (still going strong worldwide). We were led by a wide-eyed interlocutor, the bright-eyed and bushy-tailed Alastair Sooke, to the throbbing beat of – what else? – pop music, Elvis and much else besides.

Sooke protested a bit too much, doing down the previous big deal in modern art, Abstract Expressionism, in order to enhance the revolutionary nature of Pop in its fascination and appropriation of the tropes of advertising and consumerism. He infectiously enjoyed driving about under the Californian sun in a snazzy black convertible, at least one of the benefits of the American dream. With the subtitle "How Pop Art Changed the World", his thesis was stimulating, intriguing and at times persuasive, not only that Pop used capitalist techniques to subversive ends, but visually predicted the sweep – and even destructive nature – of global capitalism. In other words, the world and Pop marched hand and hand into the consumer hell, Pop sniggering along the way.

All completely authentic – except that the tins, boxes and cartons were totally empty

This made it fitting that the chronological narrative concluded with an interview with the Shanghai-based contemporary Chinese artist Xu Zhen. Obviously really, really smart, Xu Zhen even looked like a young banker, black-framed spectacles and all. He has his own company called MadeIn, a successful yet also ironic commentary in itself on corporate conceits, dedicated to the production of creativity (sic). He has the ideas, and employees carry them out with a variety of craft and mechanical skills.

He premiered at an art fair showing his own supermarket (pictured below), where customers could buy from endless rows of packaged goods, all completely authentic – except that the tins, boxes and cartons were totally empty. Our Alastair marvelled at how a Coca Cola tin, standard-looking and well-sealed, could have nothing at all in it. As Andy Warhol said, good business is the best art. An extra layer of irony was accorded Xu Zhen’s oblique and even hilarious critique of capitalism by the programme's broadcast coinciding with a stock market dip based on economic bad news from China.

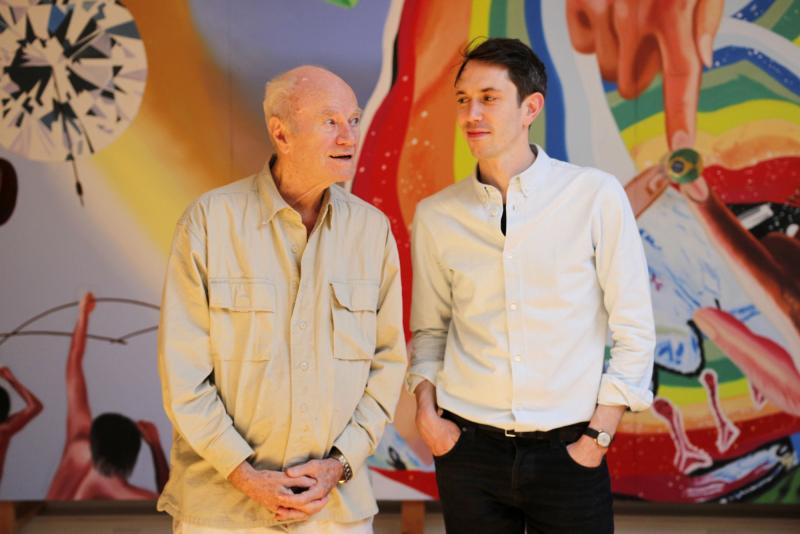

We began in New York, meeting the survivors from the 1960s, interspersed with film clips of those who have departed, from Andy Warhol, in a sense the leader of the pack, to Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg. The tone was set with a very emotive interview with James Rosenquist who, as a young man, had migrated to New York from Minnesota, and earned his living in the late 1950s working in a dangerous and skilled job painting the enormous billboards which are still such a scenic feature of the city. Rosenquist (main picture, with Sooke) is only in his early 80s – late middle-age by today’s standards – but played the laconic ancient burdened by old age to perfection, finally confounding his interviewer by saying he was tired. His F-111 (1964-1965), a 23-section painting 86 feet in length, is one of the defining images of Pop, depicting what was then the most technologically advanced fighter bomber of the Vietnam war. The American economy, the feisty Rosenquist told us, is built on selling weapons of war, his country’s prosperity still dependent, he sadly and realistically noted, on the military and defence. Plus ça change.

Pop artists in the 1960s were defined by the old guard and the critics as the New Vulgarians, accused of unfiltered appropriation of magazine and newspaper imagery. However, Sooke showed us the differences with a Lichtenstein bathing beauty painting and its original source, the artist turning and manipulating his found image into something meaningful, memorable and critical. The incredibly impassive Andy Warhol was something else: he ruthlessly used screen-printing to mass-produce his prints: as he said, he would make a portrait for anybody who asked, basing the image on his own one-off photograph, for $40,000 a pop, pun unintentional. He even had a line in portraits of dogs. He was the court painter of his day, the Van Eyck of his era, starting appropriately with a whizzy career in drawings for fashion ads.

Pop artists in the 1960s were defined by the old guard and the critics as the New Vulgarians, accused of unfiltered appropriation of magazine and newspaper imagery. However, Sooke showed us the differences with a Lichtenstein bathing beauty painting and its original source, the artist turning and manipulating his found image into something meaningful, memorable and critical. The incredibly impassive Andy Warhol was something else: he ruthlessly used screen-printing to mass-produce his prints: as he said, he would make a portrait for anybody who asked, basing the image on his own one-off photograph, for $40,000 a pop, pun unintentional. He even had a line in portraits of dogs. He was the court painter of his day, the Van Eyck of his era, starting appropriately with a whizzy career in drawings for fashion ads.

Two other American titans were interviewed. At 86, Claes Oldenburg was the elder, his career moving from 1960s happenings to huge replications of items from ice-cream cones to clothes pins. (Unseen, alas, was his unrealised project for a huge ball and cock for the Thames, to flush it away.) The younger was Ed Ruscha, the kid from Oklahoma now more than at home in Hollywood, the chronicler of parking lots and garages, not to mention the iconic HOLLYWOOD sign and other inescapable American motifs. He turned out to be a self-proclaimed patriot, ironic yes, but loving too towards the emblems and symbols of the USA.

And so to London, the swinging London of the 1960s and the jiving generation of brilliance at the Royal College of Art, caught in black and white footage of young artists dancing away before they were claimed by celebrity (or tragedy). Gorgeous Pauline Boty, who died all too young, and yes, there was Hockney, and Peter Blake (pictured below, with Sooke), and a host of others. Allen Jones, he of the stiletto shoes attached to endless female legs, still causing scandal with his sculptures of naked women that you sit on, was actually expelled from the RCA.

The case was made by Sooke – and is made by the chronology – that the first appropriations of the imagery of popular culture and mass consumption were made by these gently anarchic British artists. But while American Pop art rapidly reached a broad audience, its final accolade a ferociously condemnatory article in Life magazine, the British variant took longer to reach its audience. The Independent Group started to meet at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1952, its creative catalyst Eduardo Paolozzi, the multimedia artist who was also the master of the scrapbook, raiding advertising and comics for imagery.

The case was made by Sooke – and is made by the chronology – that the first appropriations of the imagery of popular culture and mass consumption were made by these gently anarchic British artists. But while American Pop art rapidly reached a broad audience, its final accolade a ferociously condemnatory article in Life magazine, the British variant took longer to reach its audience. The Independent Group started to meet at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1952, its creative catalyst Eduardo Paolozzi, the multimedia artist who was also the master of the scrapbook, raiding advertising and comics for imagery.

Richard Hamilton's iconic, seminal collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing, with lollipop saying POP among its bodybuilders and movie stars, dates from 1956, and the group of like-minded artists at the This Is Tomorrow show at the Whitechapel in the same year incorporated their iconoclastic views, much influenced by then-guru Marshall McLuhan: the medium is the message. Peter Blake traced his fascination to his war time trauma of childhood exile and countryside evacuation to a religious fanatic. His Self-portrait with Badges, 1961, and the record cover created with his first wife Jann Haworth for Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band, 1967, confirms that Pop was really a British innovation. Typically, the Brits invented, but failed to exploit. Even Swinging London could not replicate American energy, nor the commercial gallery backing.

A real revelation for the Anglophone viewer was the use of Pop in the carry-on of 1968, the revolution that never was, as we were introduced to the Atelier Populaire which, using Warhol’s innovative screen print techniques, churned out hundreds of posters daily posted all over Paris in response to the événements.

Jude Ho's film was impressive and informative, and even Sooke’s naïvely sincere generalisations of Pop’s undying importance and significance had a provocative charm of their own. In three weeks time The World Goes Pop opens at Tate Modern, taking a look at how the genre developed in the 1960s and 1970s – so we can test it all out for ourselves.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment