The Father, Wyndham’s Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

The Father, Wyndham’s Theatre

The Father, Wyndham’s Theatre

Well-deserved West End transfer for Florian Zeller’s powerful portrait of dementia

Dementia is an increasingly common theme in theatre, television and film. But although there are plenty of stories about old people suffering from Alzheimer’s, what does it feel like to experience this condition?

Eighty-year-old André lives in a posh flat in Paris. He is suffering from loss of memory; he finds it difficult to recognise people he knows. His grown-up daughter Anne is worried, can’t cope and decides that he should move in with her and her partner Pierre. When his condition worsens, the couple discuss sending him to a nursing home. This is what happens, or is it? Maybe. Or maybe André’s condition is so bad that Anne decides to leave him while she goes away to London to live with Pierre, the new man in her life.

André is like Kafka’s K – a victim of unjust events beyond his control

Not only is the storyline uncertain, but, within minutes, André’s disorientation, his feeling that his memories and his sense of time are fugitive, is established. Is that strange woman in the flat a care-worker, or is she his other daughter, who is absent from his daily life? What does his daughter Anne look like: blond or brunette? Who is that man? Is it Pierre, and is he friend, or foe? Who is speaking and what do they want? Are they nurses or just thieves?

Zeller’s play tells its handful of incidents – a visit, a meal, an awakening – from the subjective point of view of André so the whole point is that he cannot be sure of what is happening to him. He feels raw emotions; his nerves are frayed; he longs to be mothered by his daughter; he lapses into a second childhood. At the same time, there is a literary edge to this nightmare: André is like Kafka’s K – a victim of unjust events beyond his control. At times, the violence of the language is reminiscent of Pinter: “How much longer,” asks Pierre viciously, “do you intend to hang around, getting on everyone’s tits?” It’s a clear echo of the interrogation scene in The Birthday Party.

By the end of the play, or perhaps from its very beginning, André is bedbound in a Beckettian stasis. His universe has shrunk to his sheets and his pillows and his nurse and his pills. He is free to fantasise. He once worked as a tap dancer; he used to be in a circus. He is Lear, “a very foolish fond old man”. But, at the same time, he is full of fear; needy; desperately afraid. He is living an utter nightmare. It’s worse than folly; it’s sheer horror. And the play suggests that this might be a state that is waiting for all of us.

Christopher Hampton’s clean translation lends André a couple of verbal ticks, but most of the text is both precise and slightly impersonal. It’s efficient without being intrusive. As the furniture disappears from this old man’s world, providing a strong visual metaphor of his memory loss, James Macdonald’s production fizzes and jumps during the baroque music of the scene changes as if André’s mind was a record being dissolved in acid. But the most impressive part of this 90-minute show is the acting.

Christopher Hampton’s clean translation lends André a couple of verbal ticks, but most of the text is both precise and slightly impersonal. It’s efficient without being intrusive. As the furniture disappears from this old man’s world, providing a strong visual metaphor of his memory loss, James Macdonald’s production fizzes and jumps during the baroque music of the scene changes as if André’s mind was a record being dissolved in acid. But the most impressive part of this 90-minute show is the acting.

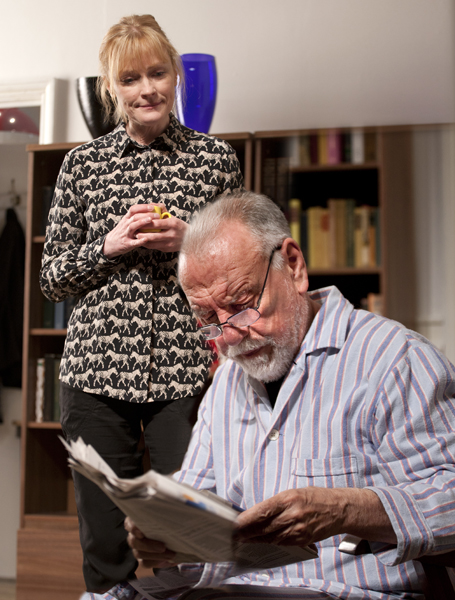

Kenneth Cranham’s André is a strong, bear-like figure whose authority is visibly leaching away. He can, perhaps in his own mind, be charming to attractive women; he can be rational. But he can also be violent. Paranoid. Crazy. And he can imagine suffering violence. It’s an uncomfortable performance, brilliant in its understanding and its detail. Similarly, Claire Skinner is a woman holding it together, but only just; any worsening of her father’s condition could simply blow her away. She is everywoman worried about her father. Both (pictured above) are well supported by Nicholas Gleaves as Pierre, Kirsty Oswald as a care-worker, plus Jim Sturgeon and Rebecca Charles in the other fragmentary roles. Despite its moments of unexpected humour, this is a sobering evening of cold comfort to anyone who is afraid of growing old.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment