When Bowie and Boyd hoaxed the art world | reviews, news & interviews

When Bowie and Boyd hoaxed the art world

When Bowie and Boyd hoaxed the art world

Nat Tate was a very Modern Painter, invented by William Boyd with the rock star's encouragement

In 1994 the art magazine Modern Painters invited fresh blood onto its editorial board. The new intake included a novelist, William Boyd, and a rock star, David Bowie. "That’s how I got to know him," says Boyd. "We’d sit at the table with all these art critics and art experts feeling like new boys slightly having to prove ourselves. He interviewed Balthus, he interviewed Tracey Emin.

But there was another contribution made by Bowie (who was privately a painter, collector and autodidactic connoisseur), and as a story it was still running four years ago. In 2012 a drawing was put up for auction at Sotheby’s by an American artist of vanishing obscurity who, in 1960 at the age of 31, committed suicide by hurling himself off the Staten Island ferry, having previously destroyed the lion’s share of his archive. The rarity value of the drawing, the title of which was Bridge No 114, was considerable. Of the tiny handful of extant works, none had appeared on the open market in living memory.

The artist was Nat Tate. Except that the drawing was actually by none other than Boyd. To spool back to beyond the beginning, it was Boyd’s initial ambition to paint rather than write. “There’s no doubt that my first artistic love was in the plastic arts, not the written one,” he told me in a plushly carpeted, wood-walled boardroom in Sotheby’s. “I was very good at art and my art teacher was saying, ‘You really should think about going to art school.’ But the parental hand firmly barred the way and so I went to university and read English literature and philosophy.” The rest is literary history.

Jackson Pollock’s drawings are lamentable. Nat’s in a different league

The novel which established him as more than a purveyor of knockabout comic fiction was the fake memoir The New Confessions. It was the first of a semi-accidental trilogy, spanning the 20th century and bookended by the compendious fake journal Any Human Heart. Its middle component was Nat Tate. “I was trying to say, ‘We are obsessed with the real, with documentary reportage and 24-hour rolling news, but actually fiction is more powerful than its rival. And so I ate the brain of my enemy to make me more powerful and produced a work of non-fiction which in fact was an absolute tissue of lies. And it worked.”

Boyd’s short life of Tate – it was more of a glossy pamphlet but tricked out with all the apparatus of biography – was published in 1998. That it became a book rather than an article in Modern Painters was partly down to Bowie, who suggested it would work better at book length. He not only brought it out in his own imprint, he also supplied the blurb on the jacket: "The small oil I picked up on Prince Street, New York, must indeed be one of the lost Third Panel Triptychs. The great sadness of this quiet and moving monograph is that the artist’s most profound dread – that God will make you an artist but only a mediocre artist – did not in retrospect apply to Nat Tate.” The launch at Jeff Koons’s studio in New York took place, with a commendably straight face, on April Fool’s Day. "It became a news event and the presence of people like Jeff Koons and Bowie made it even more glamorous." There was a healthy turnout of cognoscenti from the art world, the more senior of whom seemed dimly to recall attending shows in the 1950s which featured Tate’s work. If anyone had never heard of Tate, none was inclined to say so.

And yet they couldn’t have heard of him. As was soon reported, Tate, named after a well-known British gallery (his first name is short for National), did not in fact exist. Nor did Janet Felzer, the downtown gallerist said to have championed his work. He had never slept with Gore Vidal, despite the novelist’s claim, nor been introduced to Picasso in France by Picasso’s biographer John Richardson. These two impeccable affidavits suggested that this could not possibly be a prank. But when the London launch came around a week later, by which time many British critics had privately been taken in, the entire story had been anointed as one of the great hoaxes.

Nat Tate gained traction as a brilliant contrivance for pulling the rug from under the critical bombastocracy which makes and breaks the careers of young artists. That was never Boyd’s intention. “It was meant to be a parable about artistic fame: you’re not very good – and I can’t think of any number of people who fit that category – but you sell for huge sums of money. It became a hoax and it’s never got free of that label. It was more, I hope, a tribute to the powers of a writer’s invention that you could create something out of nothing and there was a photograph of David Bowie holding the book, there was a quote from Gore Vidal saying he was a good-looking drunk who unlike many American artists was unverbal.”

The story grew into a kind of Frankenstein’s monster. Boyd had “15 minutes on Newsnight with Paxo, which was pretty extraordinary”, did countless press and radio interviews, and participated in three separate documentaries featuring Tate. He became the go-to rent-a-quote every time a new hoax loomed into view, and wrote the introduction to a collection of anonymous photographs much like those he sourced in French junk shops and presented as images of his characters, from a youthful Tate to an elderly Braque.

The artist who never lived refused to die. Partly, it must be said, with the contrivance of an author evidently still a little in love with his creation. At weddings or christenings Boyd might present a freshly daubed Tate which, being Tate’s biographer, he is uniquely placed to authenticate. Bloomsbury issued a glossy new reprint, and the publication of a German edition found him lecturing 350 chin-strokers at a swanky gallery in front of a 20’ x 20’ image of Tate and banging out 200 Tate doodles for a limited edition. “The fuss was mindboggling. I just thought this is getting out of hand.”

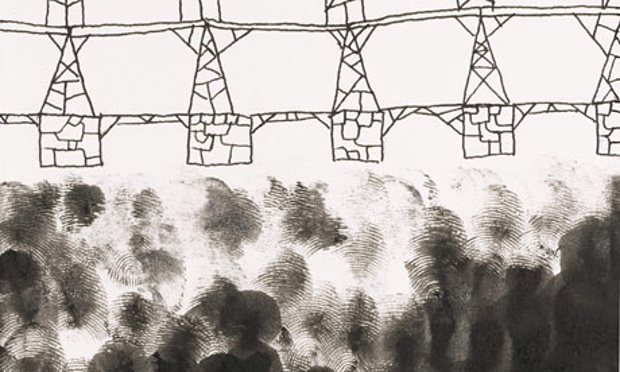

Pictured: Nat Tate's Bridge No 114 (detail)

Pictured: Nat Tate's Bridge No 114 (detail)

Nat Tate eventually penetrated the ultimate inner sanctum of Sotheby’s, with the proceeds going to the Artists General Benevolent Institution. Sotheby’s were game, having recently sold a Bruno Hat, the artist fabricated in 1929 by Evelyn Waugh’s Oxford muckers. The framed work was a small line-drawing showing a bridge depicted with childlike directness. Under it was a dense mess of black fingerprints – Boyd’s, of course. It was one of a series of bridge drawings – apparently inspired by Hart Crane’s epic poem “The Bridge”, itself inspired by Brooklyn Bridge – said to run to over 200.

“You can see the same fanatic tropes appearing,” Boyd explained, who was quick to defend Tate’s talent. “I know from the abilities of Nat Tate’s peers that actually he was as good a drawer as most of them. Some of them couldn't draw a house if you put them in front of it. Jackson Pollock’s drawings are lamentable. Nat’s in a different league.”

While not the type to be haunted by such things, Boyd gave voice to a lingering anxiety that, between them, his laboratory experiment and Tate’s slender talent may end up claiming top billing on his headstone. “I have a horrible feeling that when I’m dead and gone I’ll be remembered for Nat Tate and my novels will be mouldering and forgotten.”

And what happened to him and Bowie on Modern Painters? "We were all fired, including Mr Bowie. It was a like Politburo purge. We were airbrushed out and not a word of thanks. It was sold and suddenly we were all gone except for Matthew Collings. I was kicked out, Bowie was kicked out. If you’re going to fire your board you make sure you don't fire him."

'He played it left hand': read more about David Bowie on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment