Botticelli Reimagined, Victoria & Albert Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Botticelli Reimagined, Victoria & Albert Museum

Botticelli Reimagined, Victoria & Albert Museum

Was the Renaissance master a pioneer of brand identity?

A gallery chock-full of Botticellian lips and tits is no place to start disputing the central premise of this show, that the Florentine artist’s paintings are woven into the fabric of our collective visual consciousness. From tuppenny ha’penny statuettes to a Dolce & Gabbana trouser suit printed with fragments of the Birth of Venus, Botticelli’s most famous paintings, whether in spirit, pastiche or frank reproduction, are everywhere.

Evidence of the extent to which Botticelli’s Venus has become naturalised into our visual lexicon is no more compelling than in Rineke Dijkstra’s Beach Portraits, 1992. There are no warm Mediterranean waters here, or sultry breezes to push Venus to shore, but the contrapposto sway of the body, the windblown hair and the melancholy gaze are unmistakable and yet, we are told, entirely accidental.

We only need the slightest of cues to recognise the reference: in Alain Jacquet’s Camouflage Botticelli paintings from the early 1960s, it is the hair streaming out to one side that makes the allusion clear, even when Venus’s shell has been subsumed into the branding of Shell oil.

We only need the slightest of cues to recognise the reference: in Alain Jacquet’s Camouflage Botticelli paintings from the early 1960s, it is the hair streaming out to one side that makes the allusion clear, even when Venus’s shell has been subsumed into the branding of Shell oil.

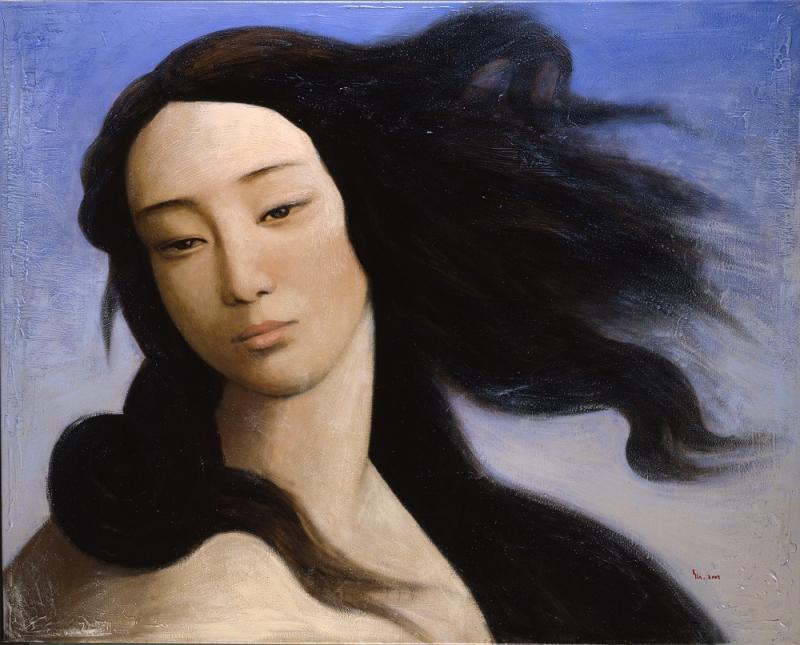

It’s a powerful testament to the emblematic quality of Botticelli’s work, his early training as a goldsmith’s apprentice generally credited with nurturing his unmistakable linear style and mastery of disegno. Certainly, the ease with which Botticelli’s Birth of Venus can be reduced to a motif is an important element of its success (main picture: Yin Xin, Venus after Botticelli, 2008). And then there is the face: disarmingly modern, it slips all the more easily into advertising imagery, film and fashion. The alarming contortions involved in creating such an alluring outline go entirely unmentioned; whether our easy acceptance of the unnaturally stretched neck and oddly-attached arms is evidence of Botticelli’s artistry or our warped expectations for female beauty is a moot point.

To claim that Botticelli’s most famous goddesses are ubiquitous just because he created a sort of ultimate pin-up is to do him a disservice, but the reasons for their exceptional hold on us remain elusive and are never fully examined here. The absence of Primavera, 1477-82, and the Birth of Venus, 1482-5, neither of which will ever again leave the Uffizi, leave us unable to analyse these superlative paintings in any meaningful way.

Nevertheless, Botticelli’s images have always been eminently reproducible, not just latterly, but by the artist himself, his workshop and his followers (pictured above right: David LaChapelle, Rebirth of Venus, 2009). Dedicated to Botticelli’s art in his own time, the final part of the exhibition shows, as the curators put it, the “variety of ways in which a painting can be ‘by’ Botticelli”, highlighting the problematic tendency, prevalent in connoisseurship of the 19th and early 20th centuries, to favour the notion of the single, autonomous master.

Early efforts to define the distinguishing characteristics of an artist’s hand in a systematic way struggled to take full account of the workshop system of the Renaissance, which in Botticelli’s case was large and extremely busy. From multiple iterations of a Virgin and Child, instantly recognisable as Botticellian but painted variously by his workshop, or even by artists with little or no connection to the master himself, we can see how Botticelli’s images have consistently been reused and repurposed.

Picking our way through a bombardment of derivative imagery, some good but much not so, it’s worth remembering just how recently Botticelli was rediscovered. While Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo have enjoyed sustained and undimmed reputations, Botticelli’s fame was already on the wane by the time of his death, and he disappeared into complete obscurity until the 19th century.

Picking our way through a bombardment of derivative imagery, some good but much not so, it’s worth remembering just how recently Botticelli was rediscovered. While Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo have enjoyed sustained and undimmed reputations, Botticelli’s fame was already on the wane by the time of his death, and he disappeared into complete obscurity until the 19th century.

It’s hard to imagine how the history of art looked without him, and the middle portion of this exhibition is dedicated to the rehabilitation of Botticelli's reputation not just by connoisseurs and collectors, but by Pre-Raphaelite painters like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, whose aesthetic values chimed with Botticelli’s lush draperies, gorgeous women and quasi-pagan iconography (pictured left: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, La Ghirlandata, 1873).

The emphasis is on the assimilation and influence of Botticelli’s imagery in 19th-century art, but a more interesting current runs alongside the principal theme. Copying was an important aspect of the study of art in the 19th century and not just for artists. Good copies were an essential tool for the nascent discipline of art history, and were a cornerstone of the collections on display in the new public museums and galleries, like the V&A itself and its famous Cast Courts.

Naturally, Botticelli’s revival in the 19th and early 20th centuries offered tempting opportunities for forgers. Easy to miss here, but worth seeing for its folkloric value alone, is the Madonna of the Veil, once thought to be by Botticelli and now known to have been produced in the 1920s by Italian forger Umberto Giunti. Botticelli's women are celebrated for their timeless beauty, but the wonderful irony is that this forgery was discovered when the eagle-eyed Kenneth Clark recognised the carefully preened eyebrows and rosebud lips as entirely 20th century and incriminatingly reminiscent of the film star Jean Harlow.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment