A Jubilee for Anton Chekhov, Hampstead Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

A Jubilee for Anton Chekhov, Hampstead Theatre

A Jubilee for Anton Chekhov, Hampstead Theatre

Michael Pennington on saving the playwright's house, with a little help from friends

The Russians have always been good at writers' houses. The Soviets especially. When I first saw Tolstoy's house his blue smock was hanging behind the door, a manuscript was on his desk but the chair pushed back as if he'd nipped out for a moment and would be back. It was a frankly theatrical effect and the better for it.

When I went to Melikhovo in 1997 it was in the hands of dedicated individuals rather than the state, and while it was certainly pleasant to have an American and a German tour group held at the door so that I, “aktor Angliskie”, could spend half an hour in there on my own, communing, it was disturbing that the information being given out about the house wasn’t always strictly accurate; and far more of it had been restored (a euphemism for copied) than was being acknowledged.

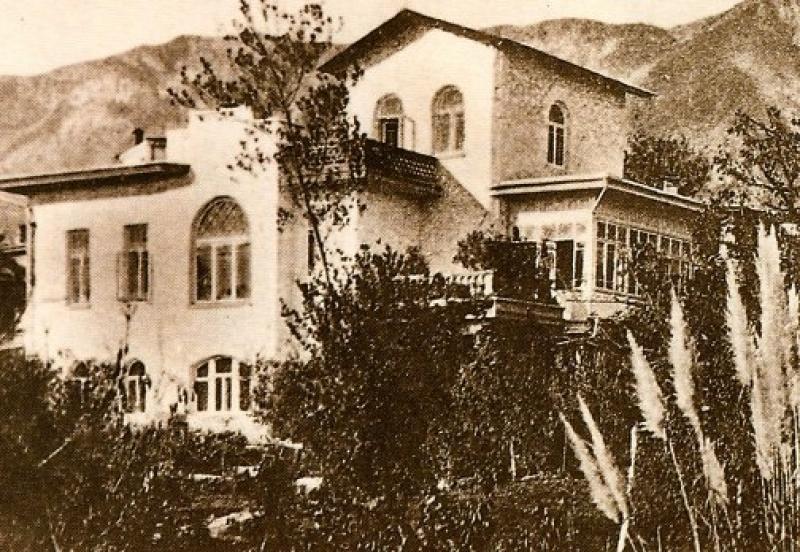

The White Dacha in Yalta (pictured), where Chekhov spent the last five years of his life – and wrote Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard - is a different matter: it is much more difficult of access and so never likely to be a tourist attraction, but by contrast it genuinely sings with Chekhov’s spirit. Discreetly tucked away in the midst of beautiful gardens planted by himself, it has the same ambiguous welcome-them but dread-them feel about visitors that Chekhov himself had. Chekhov loved the house, designed it and oversaw its construction, boasting that he had "all the American conveniences" (whatever that quite meant) and one of the first private telephones in the area, on which he could talk to Tolstoy.

The White Dacha in Yalta (pictured), where Chekhov spent the last five years of his life – and wrote Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard - is a different matter: it is much more difficult of access and so never likely to be a tourist attraction, but by contrast it genuinely sings with Chekhov’s spirit. Discreetly tucked away in the midst of beautiful gardens planted by himself, it has the same ambiguous welcome-them but dread-them feel about visitors that Chekhov himself had. Chekhov loved the house, designed it and oversaw its construction, boasting that he had "all the American conveniences" (whatever that quite meant) and one of the first private telephones in the area, on which he could talk to Tolstoy.

The house, like Chekhov himself, is an extraordinary mixture of high aspiration and matter-of-fact detail. Chekhov longed for a better life but preferred to talk to his guests about neckties. His house is imposing and confident but cosily welcoming within. The entrance hall wide open and friendly, with a case holding champagne glasses that his parents drank from on their wedding day. On the first landing is a wardrobe with the boots and leather coat in which he crossed Siberia, as well as his shirts and summer hats, straight out of the photographs. His sister has a warm and airy room at the top – she was a talented painter. The room he gave to his mother – a pious woman who outlived him by 15 years - is quite stark, with an ikon on the wall. On the wall of the realist Chekhov’s bedroom, on the other hand, hangs a satchel he used when conducting a local census years before – his ikon for progress.

Leading off from the bedroom is the heart of it all - Chekhov’s study, designed for ease (and failing health), with a bed behind his writing chair to collapse into, a view of the bay, a favourite landscape painting on the wall in front of him, everything to hand. In a corner are the hideous gifts the Moscow Art Theatre gave him on the first night of The Cherry Orchard – gifts he detested, whatever the ever loyal museum staff tell you.

When my friend Rosamund Bartlett told me what had been allowed to happen to the house in the last few years, I was shocked. The Russian government declines responsiblility for it because since the upheavals in Russia it sits in independent Ukraine. Meanwhile the Ukrainians say, “Well, he was a Russian writer,” and they demur as well. The modicum of government support the house gets comes from the small Crimean Autonomous Region within the Ukraine. Between 2003 and 2007 cracks appeared, the wallpaper peeled, and the land around was surveyed by speculators.

Thanks to the director Ala Golavacheva and her dedicated team – which includes an elderly lady who started work there in the 1950s when Chekhov’s sister was still alive and who knew her well - private money has been raised privately for immediate repairs and adequate security. What is still desperately needed is a long-term contingency so that staff can be paid and problems dealt with as they come up.

Rosamund had just started the Yalta Chekhov Campaign to help, and the idea soon arose for us foreigners to go further – a week at Hampstead, say, with writers talking about their favourite Chekhov stories. The writers include William Boyd, Richard Eyre, William Fiennes, Michael Frayn, David Hare and Lynne Truss. I added the showbiz element, a top-line cast of performers for the week: Eileen Atkins, Simon Russell Beale, Miriam Margolyes, Rosamund Pike, David Horowitz and Penelope Wilton. And as it’s roughly his 150th birthday it’ll be a celebration with some usefulness. And very Chekhovian – apprehensive about the future, but comic and full of hope.

You could ask why it matters about bricks and mortar when the hero’s gone. In Chekhov’s particular case, it matters quite a lot. He is loved everywhere, by actors, by writers and by the public. We feel an intimate connection with this wise, complex and above all unassuming man. But he remains elusive, a mystery in the final account. The house tells you much about him in his last years – his sense of proportion, his courage, his feeling for what was right for the people he dealt with. There is no good reason I can think of why future generations should not have the same opportunities we have had, some chance of the same proximity. Better that than that a prospector like Lopahin in The Cherry Orchard should buy the land, knock down the cherry trees and build holiday apartments. And believe me, it could happen.

A Jubilee for Anton Chekhov is at Hampstead Theatre from 18 to 23 January.

A Jubilee for Anton Chekhov is at Hampstead Theatre from 18 to 23 January.

Monday 18 January, 7.30pm

Chekhov's Vaudevilles

Michael Frayn with David Horovitch, Miriam Margolyes and Steve McNeil

Tuesday 19 January, 7.30pm

Chekhov's Women

Lynne Truss on "In the Cart" and "The Darling" with Rosamund Pike

Wednesday 20 January

Chekhov's Major Plays

Richard Eyre with friends

Thursday 21 January, 7.30pm

Chekhov's Doctors

William Boyd on "Ionych" with Eileen Atkins

Friday 22 January, 7.30pm

The Perfect Short Story

David Hare on "Lady with the Little Dog" with Penelope Wilton

Saturday 23 January, 3pm

Anton Chekhov

An afternoon in the company of the elusive Russian playwright in the form of a narrative comprised of Chekhov’s own words. Written and performed by Michael Pennington (pictured above).

Saturday 23 January, 7.30pm

Chekhov and Unrequited Love

William Fiennes on "Verochka" with Simon Russell Beale

Official website of Yalta Chekhov Campaign.

Read an extract from Michael Pennington's acclaimed book, Are You There, Crocodile?: Inventing Anton Chekhov (Oberon Books)

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Add comment