theartsdesk in Yasnaya Polyana: The Lost Centenary of Tolstoy's Death | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Yasnaya Polyana: The Lost Centenary of Tolstoy's Death

theartsdesk in Yasnaya Polyana: The Lost Centenary of Tolstoy's Death

Russia's ambivalent relationship with the writer underlined by muted centenary

Russia marks the centenary of the death of Leo Tolstoy on 20 November – but the level of local tribute to one of the country’s greatest writers seems markedly muted for a figure two of whose novels, Anna Karenina and War and Peace, are regularly ranked in Top 10 lists by writers and readers around the world.

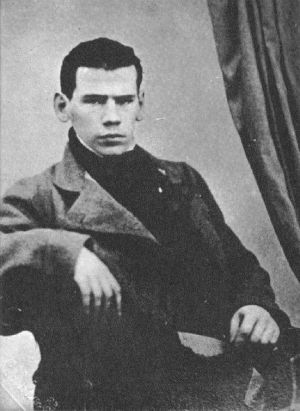

Tolstoy is a figure of such an enormous scale, both in his work and in his life, that contradictions inevitably abound: the youthful soldier who later became one of the most vocal pacifists of his time; the philanderer whose lengthy diaries record his youthful battles with his considerable sexual urges who yet went on to be one of the stricter moralists of the era; the aristocratic landowner who would later insist that copyright in his literary work go for free into the public domain; and the social activist whose comrades and fellow thinkers were imprisoned or exiled, while he himself was protected by close relatives at the Imperial court. The place to start any investigation of this paradoxical figure is Yasnaya Polyana, the estate where he was born and would spend the greater part of his life.

More than anywhere else the place catches the character of the man. Working on a BBC Imagine programme due to be broadcast early next year, I was a frequent visitor there over the summer. A journey of three hours or so south of Moscow, it’s an idyll indeed after the traffic and confusion of the Russian capital (its name means Bright Glade). I first came here almost 20 years ago and, unlike almost everything else in the country, Yasnaya Polyana has hardly changed. It’s a backwater in the very best sense, with the estate house (pictured right) still reached on foot up the birch alley.

More than anywhere else the place catches the character of the man. Working on a BBC Imagine programme due to be broadcast early next year, I was a frequent visitor there over the summer. A journey of three hours or so south of Moscow, it’s an idyll indeed after the traffic and confusion of the Russian capital (its name means Bright Glade). I first came here almost 20 years ago and, unlike almost everything else in the country, Yasnaya Polyana has hardly changed. It’s a backwater in the very best sense, with the estate house (pictured right) still reached on foot up the birch alley.

The only vehicles usually allowed are those related to the working farm that, as in Tolstoy’s day, manages the property, principally its apple orchards (in their time apparently among the largest in Europe). The estate itself is much reduced in size today: after Tolstoy’s death in 1910 some land was given away to his peasants, while more was redistributed after the 1917 revolution. The stables, from which Tolstoy departed in the early morning hours on the dramatic journey in the last days of his life, escaping from home and conflicts with his wife, still have working horses in them to this day. The story of those last days became more widely known this year thanks to The Last Station, Michael Hoffman’s film dramatisation of Jay Parini’s novel starring Christopher Plummer and Helen Mirren as the Tolstoys.

The Last Station was released in Russia this week, earning considerably more favourable reviews than Russian critics usually give to foreign fare treating Russian stories or histories. It puts the conflict between Tolstoy’s wife, best known by her name and patronymic, Sofya Andreievna (pictured left with Tolstoy), and his chief disciple Vladimir Chertkov at the centre of the film, as they vie for Tolstoy’s loyalty and final inheritance. It’s a conflict of interest that has usually seen Sofya vindicated as Tolstoy’s long-suffering wife.

The Last Station was released in Russia this week, earning considerably more favourable reviews than Russian critics usually give to foreign fare treating Russian stories or histories. It puts the conflict between Tolstoy’s wife, best known by her name and patronymic, Sofya Andreievna (pictured left with Tolstoy), and his chief disciple Vladimir Chertkov at the centre of the film, as they vie for Tolstoy’s loyalty and final inheritance. It’s a conflict of interest that has usually seen Sofya vindicated as Tolstoy’s long-suffering wife.

One American Tolstoyan, visiting Yasnaya Polyana this summer, commented on how the layout of the museum itself tacitly takes Sofya’s side. Tolstoy’s first English-language biographer, Aylmer Maude, a long-time disciple of the writer who with his wife spent much of his life translating the complete works into English, also comes across as partisanly as can be imagined in his opposition to Chertkov. Nevertheless after the 1917 revolution Chertkov devoted himself fanatically to finishing the edition of Tolstoy’s complete works, which found him petitioning Lenin, and later Stalin. So slow and complicated was the process that the final volume appeared only in the 1950s, 20 years after Chertkov’s death.

(For a very different perspective on this household battle of wills from that found in The Last Station, a silent film made by Russian director Yakov Protozanov, The End of a Great Man, made only two years after Tolstoy’s death, is a hilarious, and much more melodramatic portrayal of those final days; it ends, somewhat improbably, with his being welcomed into heaven by Christ. Made against the considerable opposition of the Tolstoy family, it was hardly screened at all in Russia at the time of its release.)

Watch a clip from The End of a Great Man:

The fact that the small estate house at Yasnaya Polyana survived the 1917 revolution at all, when many other such vestiges of the previous era were being looted, is testimony both to Sofya Andreievna’s determination, and to the writer’s partial co-option by the new Communist regime (a connection symbolised by Lenin’s famous essay of 1908 that termed Tolstoy the “mirror of the Russian revolution”). But survive it did, and there remains something very domestic to the 12 or so rooms that in their time astonishingly housed the large Tolstoy family, not to mention their many and often illustrious guests.

There had been a grander house on the site before, but Tolstoy, whose other youthful failing was gambling, most often with his fellow military officers, lost it at cards: that saw the building disassembled stone by stone and moved to a new location not far away for a new owner (it does not survive today). When asked in later years where he was born, Tolstoy would point up into the branches of one of the trees planted in the place where the old house once stood, saying “somewhere up there”.

There had been a grander house on the site before, but Tolstoy, whose other youthful failing was gambling, most often with his fellow military officers, lost it at cards: that saw the building disassembled stone by stone and moved to a new location not far away for a new owner (it does not survive today). When asked in later years where he was born, Tolstoy would point up into the branches of one of the trees planted in the place where the old house once stood, saying “somewhere up there”.

The Tolstoy family connection to Yasnaya Polyana itself more than survives today. Sofya Andreievna was its informal first curator of the estate house, showing it to the many visitors who visited up until her own death in 1919, while Tolstoy’s youngest daughter Alexandra would assume such an official responsibility during the 1920s, before she went abroad in 1928, never to return to the Soviet Union.

Since 1994 another descendant, Vladimir Tolstoy (pictured below left, with Catharina and Anastasia Tolstoy and Helen Mirren), previously a Russian journalist, has overseen the estate (keeping things in the family, his wife also runs the kindergarten in the village, which itself follows Tolstoy’s educational methods). Keen to preserve a sense of the dynasty, Vladimir Tolstoy has been organising periodic reunions of family members at Yasnaya Polyana: the number of direct descendants from Lev Nikolaievich’s marriage with Sofya Andreievna is today around 400, dispersed as far away as Sweden and Uruguay; some are descended from Tolstoy’s children who remained in Russia after the revolution, others from those who emigrated.

Their gathering in August in the centennial year was a wonderful event: some 120 descendants (more were expected but put off by the smog that hit Central Russia in August) with their families returned to their ancestral home for a week of activities, including the chance to attend jam-making classes (after a scene in Anna Karenina), as well as working at the apiary, the apple orchards and in the woods that surround the estate, which is where Tolstoy himself is buried in a simple, unmarked grave. They were welcomed at the gates of the estate on the first day by local musicians with the traditional Russian greeting of bread and salt, and the words, “Welcome to Yasnaya Polyana. Welcome to Russia!” It was a greeting that rang true, given that Tolstoy – not Pushkin, nor Dostoevsky, nor even Chekhov - is surely the Russian writer with whom foreign readers most associate their image of Russia itself.

Their gathering in August in the centennial year was a wonderful event: some 120 descendants (more were expected but put off by the smog that hit Central Russia in August) with their families returned to their ancestral home for a week of activities, including the chance to attend jam-making classes (after a scene in Anna Karenina), as well as working at the apiary, the apple orchards and in the woods that surround the estate, which is where Tolstoy himself is buried in a simple, unmarked grave. They were welcomed at the gates of the estate on the first day by local musicians with the traditional Russian greeting of bread and salt, and the words, “Welcome to Yasnaya Polyana. Welcome to Russia!” It was a greeting that rang true, given that Tolstoy – not Pushkin, nor Dostoevsky, nor even Chekhov - is surely the Russian writer with whom foreign readers most associate their image of Russia itself.

The family reunion was as intimate a tribute to Tolstoy as you could ever wish for, and of course there have been academic conferences going on throughout the year, from New York to Havana, to mention only a few. Another Russian one begins on 20 November in Astapovo - the small town now renamed Lev Tolstoy where the very ill writer disembarked from the train on his final journey and a few days later he died - before moving on to Yasnaya Polyana. But it still leaves an impression that the centenary of Tolstoy’s death has gone relatively unmarked in his native land. Imagine a similar event in Britain or France, commemorating such a date for writers whom Tolstoy so much admired like Dickens or Stendhal – or even for Alexander Pushkin, the bicentenary of whose birth in 1999 had Russia’s main television channel devoting a whole day of its airtime (news broadcasts aside) to the country’s greatest poet. Nothing of the sort is expected for Tolstoy.

In the Soviet years the centenary of the writer’s birth in 1928 and the 50th anniversary of his death in 1960 both had jubilee evenings at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, as well as extensive press coverage and international guests. This is interesting in the light of Rosamund Bartlett’s new biography Tolstoy: A Russian Life, which has a fascinating final section, titled “Patriarch of the Bolsheviks”, that details the uneasy relationship between the Soviet authorities and Tolstoy, and the ideas of Tolstoyanism which were associated with him, such as the pacifism which became increasingly unacceptable to the new regime. The ideas of early Soviet Tolstoyans, such as establishing their own communes, partly overlapped with some of the theories behind Soviet collective farms, but by the mid 1930s they were already becoming out of favour with the authorities.

In the Soviet years the centenary of the writer’s birth in 1928 and the 50th anniversary of his death in 1960 both had jubilee evenings at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, as well as extensive press coverage and international guests. This is interesting in the light of Rosamund Bartlett’s new biography Tolstoy: A Russian Life, which has a fascinating final section, titled “Patriarch of the Bolsheviks”, that details the uneasy relationship between the Soviet authorities and Tolstoy, and the ideas of Tolstoyanism which were associated with him, such as the pacifism which became increasingly unacceptable to the new regime. The ideas of early Soviet Tolstoyans, such as establishing their own communes, partly overlapped with some of the theories behind Soviet collective farms, but by the mid 1930s they were already becoming out of favour with the authorities.

Russia may still have a way to go before it recognises the full potential of such cultural dates as part of a wider tourist industry. It's sad, all the same, that the special weekend train from Moscow to the station nearest to Yasnaya Polyana, its carriages decorated with themes from the writer’s work, and from which Tolstoy’s coffin was carried home by villagers escorted by a crowd of several thousand in 1910, has not been running since the beginning of this year.

Not that other local initiatives aren’t attempting to expand Tolstoy’s presence across Russia. In Kazan in Tatarstan, where the writer and his siblings grew up with relatives after the early death of their parents, and where Tolstoy started – and then quit prematurely – university, the original dilapidated mansion that was the family home is slowly being turned into a local museum about the writer’s early life. The predicted opening date, if all goes smoothly with funding, is around 2014.

Meanwhile, on the steppes outside Samara there are plans to construct a new horse-riding resort complex. Tolstoy initially went there on health cures: the local mare’s milk, kumys, was considered beneficial for those at risk of tuberculosis. The disease had claimed one of the writer’s brothers, an incident which found its way into Anna Karenina. Tolstoy would later buy a vast estate there on the proceeds of War and Peace. Though nothing remains of his dwelling today except a memorial plaque in a deserted landscape, recent years have seen the elaborate wild horse races across the steppes that Tolstoy sponsored brought back to life.

Other locations from the writer’s early writing years, and especially his military service, also offer much, leaving hope that one day, perhaps, there will be tours of Tolstoy places around Russia. Sadly the places where he served in Chechnya at the very beginning of his military career, and where he wrote his first published work, Childhood, Boyhood, Youth, remain inaccessible for foreign visitors – although there has long been a museum dedicated to him there in Starogladkovskaya. Remarkably, it remained open throughout the years of the Chechen war, and has a visitors’ book containing entries from both senior Russian officers and Chechen separatists. One of Tolstoy’s final, posthumously published works, Hadji Murat, is highly acclaimed locally for its depiction of the eponymous 19th-century defender of Chechen nationalism who is finally, and fatally, caught in a twisted web of loyalties. It’s a sobering thought that rather more than a century after Tolstoy was in conflict there, Russian troops would once again be battling against fiercely proud local resistance in another bloody conflict.

There are plentiful such comparisons, too, with Sevastopol, where Tolstoy served during the Crimean War. His Sevastopol Sketches catch all of the confusion of warfare in an absolutely authentic way; a remarkable conference paper I heard earlier this year put Tolstoy’s descriptions of military service in that conflict up against some of the accounts being published by American soldiers in Afghanistan today, which highlighted the sense of sheer immediacy communicated by the writers on the details of conflict-zone experience. The fourth bastion where Tolstoy served is today the site of the Panorama of the Defence of Sevastopol, and you can sit on the cannons that once defended its walls against attacking French troops. The panorama itself, a remarkable 360-degree painterly depiction of the Crimean War by artist Franz Roubaud (pictured below), would itself not survive another conflict a century or so later, this time from attacking German troops in World War Two: it had to be almost fully recreated in the post-war years.

The Sevastopol Sketches are a key work in Tolstoy’s development: it was after he wrote them that Tolstoy became convinced that his destiny was to be a writer. Abandoning a possible military career, he went to St Petersburg to immerse himself in the company of the likes of the novelist Ivan Turgenev and the influential poet and literary magazine editor Nikolai Nekrasov. The three sketches date from different months of the siege of Sevastopol, and show the gradual change of Tolstoy’s views of war - from the proud patriotism of the first “Sevastopol in December” (translated into French on the personal direction of reformist Tsar Alexander II), to the disillusionment of the third “Sevastopol in August 1855”, which was considerably censored before it could be published.

Censorship probably isn’t a word we immediately associate today with a literary giant like Tolstoy, but it’s worth remembering the fact that the last 40 years of the 19th century in Russia were a time of dramatic social change, in which Tolstoy was very much a participant. With his engagement in social causes, and later in his views on religion, the writer went close to the boundaries of what was acceptable to the authorities. Looking back on Tolstoy’s life 100 years on, some similarities between the situation in Russia then and now certainly seem striking: vast gaps in wealth between the rich and poor, the remarkable closeness of church and state, censorship in one form or another and the discouragement or exile of independent voices, and a political role for the state which borders on autocracy. It is perhaps little surprise, then, that Tolstoy remains a figure of some contention today.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Ballad of a Small Player review – Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review – Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

After the Hunt review – muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review – muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Add comment