Georgia O’Keeffe, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Georgia O’Keeffe, Tate Modern

Georgia O’Keeffe, Tate Modern

Defined by sexual readings of her flowers and other paintings, the American modernist gets a much-needed retrospective

It's 100 years since Georgia O’Keeffe first showed at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in New York, a hub of avant-garde activity, and the opening room of this major retrospective revisits the 1916 exhibition. Inspired by Arthur Dow’s emphasis on freedom of expression and Wassily Kandinsky’s book The Art of Spiritual Harmony, O’Keeffe made a series of drawings and paintings in which natural forms are abstracted to the point where they are only just recognisable.

O’Keeffe was an accomplished musician and, like Kandinsky, was interested in synesthesia – the stimulus of one sense by another – especially the triggering of colour by sound. Music – Pink and Blue No 1, 1918 (pictured below right), is an exploration, as she put it, of “the idea that music could be translated into something for the eye”. Abstraction – Alexius, 1928, shows billowing clouds fringed with blue, green and purple towering above magenta vibrations; it reminds me of the “thought forms” (abstract shapes and colours) emanating from people listening to music as described by Theosophists Annie Besant and C.W Leadbeater, who inspired Kandinsky’s move into abstraction.

Such thoughts were part of the zeitgeist, but Steiglitz, who married O’Keeffe in 1924, did not promote her as an American modernist preoccupied by issues similar to her Russian and European colleagues, but as a woman governed by biology rather than ideas. “Woman feels the World differently than Man feels it,” he wrote in 1919. “The Woman receives the world through her Womb. That is her deepest feeling. Mind comes second.”

Such thoughts were part of the zeitgeist, but Steiglitz, who married O’Keeffe in 1924, did not promote her as an American modernist preoccupied by issues similar to her Russian and European colleagues, but as a woman governed by biology rather than ideas. “Woman feels the World differently than Man feels it,” he wrote in 1919. “The Woman receives the world through her Womb. That is her deepest feeling. Mind comes second.”

When photographing Music – Pink and Blue No 1, he even placed a phallic sculpture in front of the painting that encourages one to see the blue void as a vaginal opening. This crass intervention set the tone for years to come for critical responses to her work; not surprisingly, O’Keeffe was frustrated at being treated as an exotic outsider. “When people read erotic symbols into my paintings,” she wrote, “they’re really talking about their own affairs.” When, decades later, artists like Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro claimed her as a feminist forerunner, she was similarly irritated by what she felt to be another form of marginalisation.

Her refusal to accept the presence of sexual imagery in her work creates interesting problems for people like myself, who cannot look at flower paintings such as Dark Iris No 1, 1927, and Black Iris, 1926, for which she is justly famous, without seeing labial folds and vaginal orifices. This may have more to do with the structure of flowers than with the gender of the artist, though, since Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of flowers provoke in me a similar response. It's more complicated than that, though; in the case of both artists, exposing the fragile beauty of the bloom to close scrutiny feels like an act of violence and, in O’Keeffe paintings, this is often exacerbated by the vehemence of her colours and compositions.

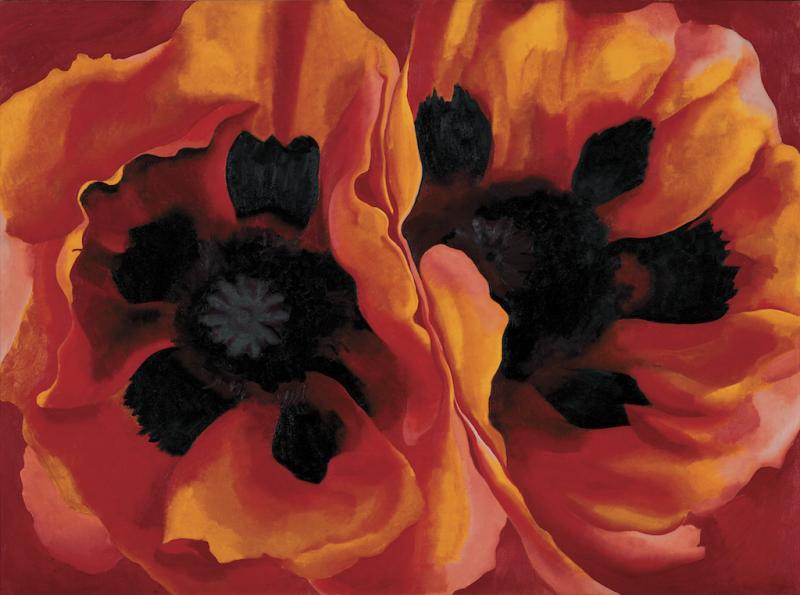

In Calla Lilies on Red, 1928, two white flowers are silhouetted against dark-green leaves that thrust upwards like an arrow splitting asunder the fleshy red ground with a dark gash. It's impossible to describe this startling image without sounding like an extract from a porn magazine. Oriental Poppies, 1927, is more subtle but equally powerful. Peering into the bright-orange petals, O’Keeffe reveals the velvety dark interior. The drama of this provocative image stems from the juxtaposition of vivid colour and intrusive close-up. Nor is it just the case with flowers: her painting of autumnal oak leaves solicits what I can only describe as a feeling of embarrassment at their pink fleshiness, and the same is true of many of her subsequent landscapes.

In Calla Lilies on Red, 1928, two white flowers are silhouetted against dark-green leaves that thrust upwards like an arrow splitting asunder the fleshy red ground with a dark gash. It's impossible to describe this startling image without sounding like an extract from a porn magazine. Oriental Poppies, 1927, is more subtle but equally powerful. Peering into the bright-orange petals, O’Keeffe reveals the velvety dark interior. The drama of this provocative image stems from the juxtaposition of vivid colour and intrusive close-up. Nor is it just the case with flowers: her painting of autumnal oak leaves solicits what I can only describe as a feeling of embarrassment at their pink fleshiness, and the same is true of many of her subsequent landscapes.

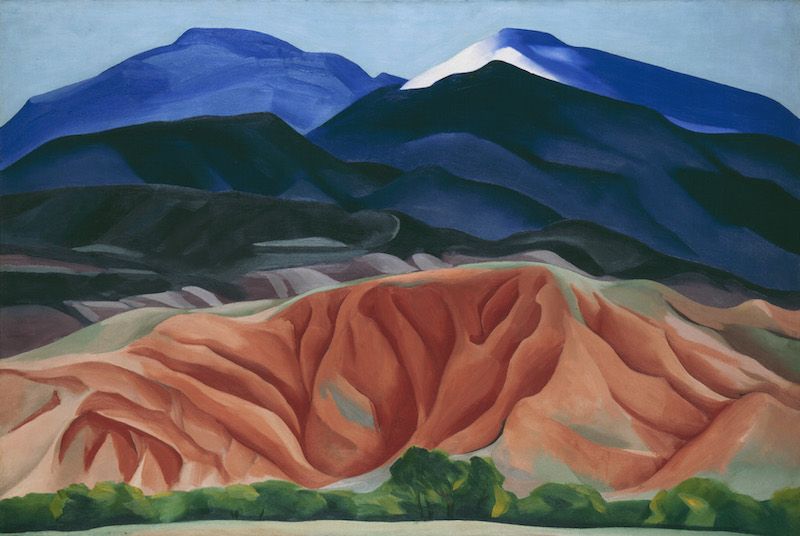

In 1929, O’Keeffe travelled to New Mexico and fell in love with the red earth and rolling hills of this desert region. She returned many times and, in 1949, after Stieglitz’s death, moved there permanently. She painted the barren landscape over and over again, and the sense of fleshiness recurs in paintings such as Black Mesa Landscape, 1930 (pictured above), and Purple Hills, 1935, whose folds, wrinkles, pleats and crevices bear an uncanny resemblance to the human body.

This fascinating exhibition reveals a far more complex and interesting artist than I can do justice to here. During a severe drought in New Mexico, O’Keeffe began collecting animal skulls and painting them with the same unstinting realism as the flowers (pictured right: From the Faraway, Nearby, 1937). They seemed to her “strangely more living than the animals walking around”, and she began juxtaposing them with flowers and euphoric views of the parched landscape, to create a mood of sardonic celebration akin to the party atmosphere of Mexico’s Day of the Dead.

This fascinating exhibition reveals a far more complex and interesting artist than I can do justice to here. During a severe drought in New Mexico, O’Keeffe began collecting animal skulls and painting them with the same unstinting realism as the flowers (pictured right: From the Faraway, Nearby, 1937). They seemed to her “strangely more living than the animals walking around”, and she began juxtaposing them with flowers and euphoric views of the parched landscape, to create a mood of sardonic celebration akin to the party atmosphere of Mexico’s Day of the Dead.

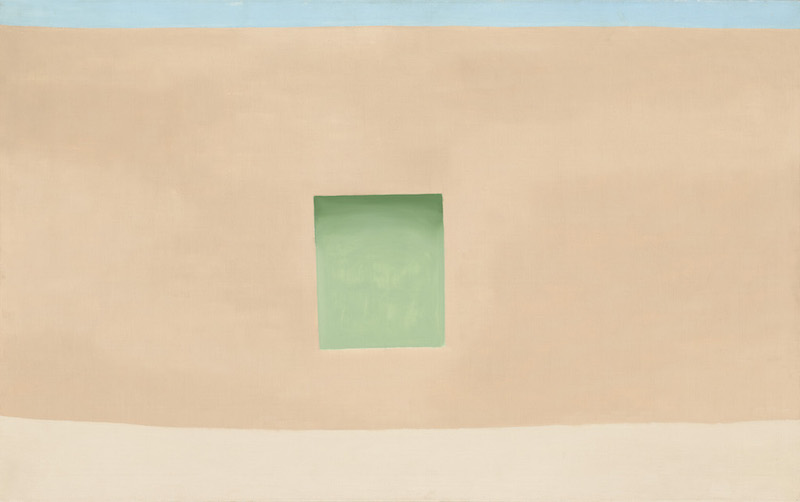

Alongside the magical realism of these bone paintings, she pursued her interest in abstracting from various landscape and architectural motifs. In 1929, she painted a frontal view of the door of the Lake George summerhouse owned by the Stieglitz family. With its pared-down geometry and almost monochrome palette, this seminal painting was to influence the abstract painter Ad Reinhardt. In 1945, she bought an adobe house in New Mexico with “a good sized patio with a long wall with a door on one side.” This bare wall sparked a series of ostensibly abstract paintings featuring one rectangle inside another (pictured below: Wall with Green Door, 1953); an exquisite painting resembling the sweep of a calligrapher’s brush over a sheet of paper, meanwhile, is based on the road arcing beneath the house through a snow-covered landscape.

Flights between New York and New Mexico prompted aerial views of cloud formations and rivers in which the background (negative space) plays as important a role as the figurative shapes. Continued throughout her career, these many forays into abstraction were to influence a generation of painters, including Agnes Martin, Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler and Kenneth Noland. They ensured Georgia O’Keeffe the central place in the story of American art that had been denied her when she was viewed as an exotic outsider, a “woman artist”. "Men put me down as the best woman painter," she complained. "I think I'm one of the best painters." There are no examples of her work in British museums, so this is your chance to decide if she was right.

Flights between New York and New Mexico prompted aerial views of cloud formations and rivers in which the background (negative space) plays as important a role as the figurative shapes. Continued throughout her career, these many forays into abstraction were to influence a generation of painters, including Agnes Martin, Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler and Kenneth Noland. They ensured Georgia O’Keeffe the central place in the story of American art that had been denied her when she was viewed as an exotic outsider, a “woman artist”. "Men put me down as the best woman painter," she complained. "I think I'm one of the best painters." There are no examples of her work in British museums, so this is your chance to decide if she was right.

- Georgia O’Keeffe at Tate Modern until 30 October

- Read more visual art reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment