10 Questions for Musician Jasper Høiby | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Musician Jasper Høiby

10 Questions for Musician Jasper Høiby

The Danish bassist on the perils of consumerism, playing without the dots, and why 4/4 isn't a crime

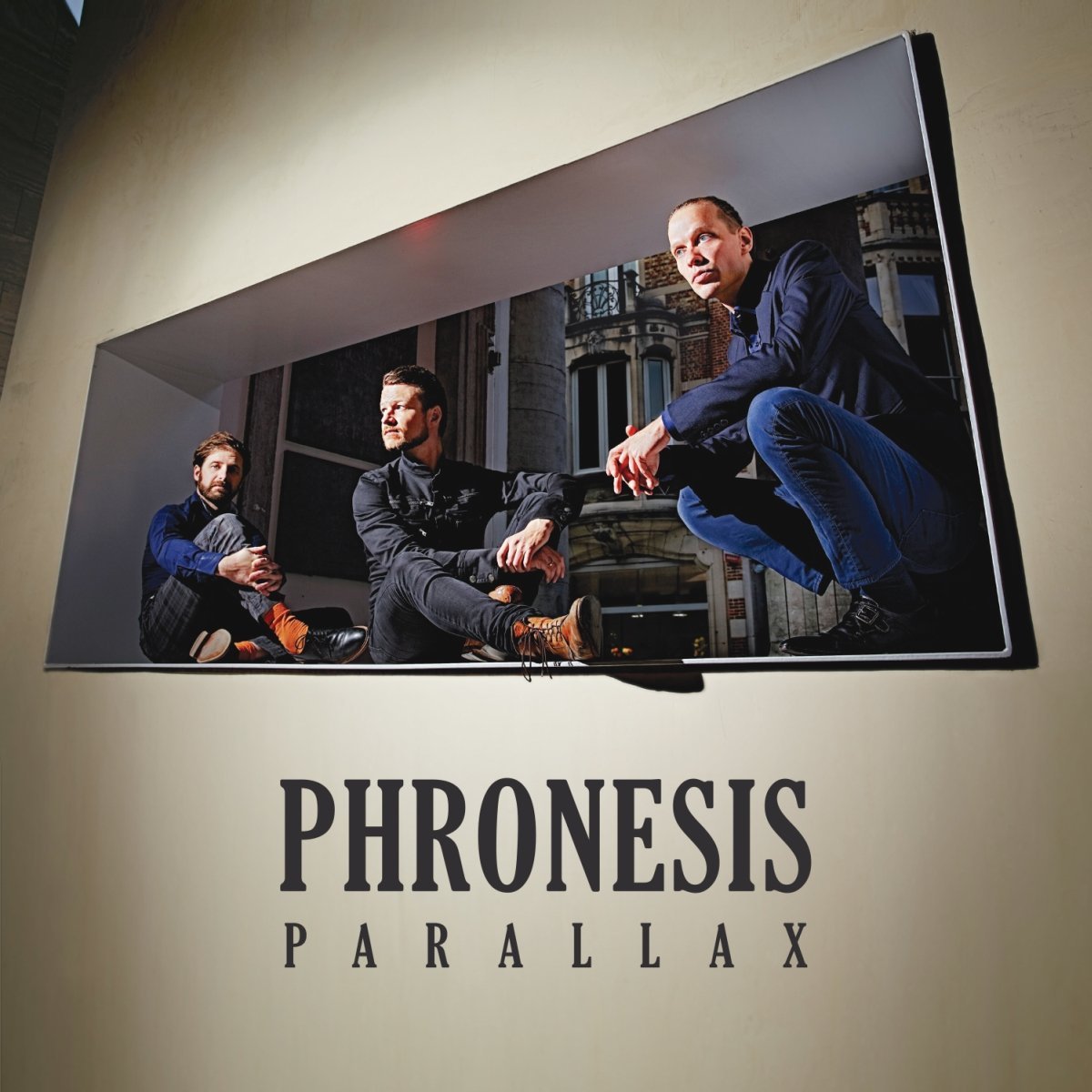

Copenhagen-born bassist Jasper Høiby moved to London in 2000 to attend the Royal Academy of Music. In 2005 he created the trio Phronesis which has toured extensively in Europe and North America and won awards for Jazz Album of the Year in Jazzwise and MOJO for its 2010 album, Alive, as well as a London Jazz Award for its "Pitch Black" performance at Brecon Jazz festival in 2012.

Høiby has performed and recorded with a number of artists including Mark Guiliana, Django Bates, Shai Maestro, Julian Joseph, Kurt Elling, Tom Arthurs, Mark Lockheart, Liam Noble, Julia Biel, Marius Neset, Kairos 4tet and Jim Hart. In 2012 he won the Copenhagen Jazz Festival's "Young Spirit Award" alongside honorary winners Jack DeJohnette and Palle Mikkelborg.

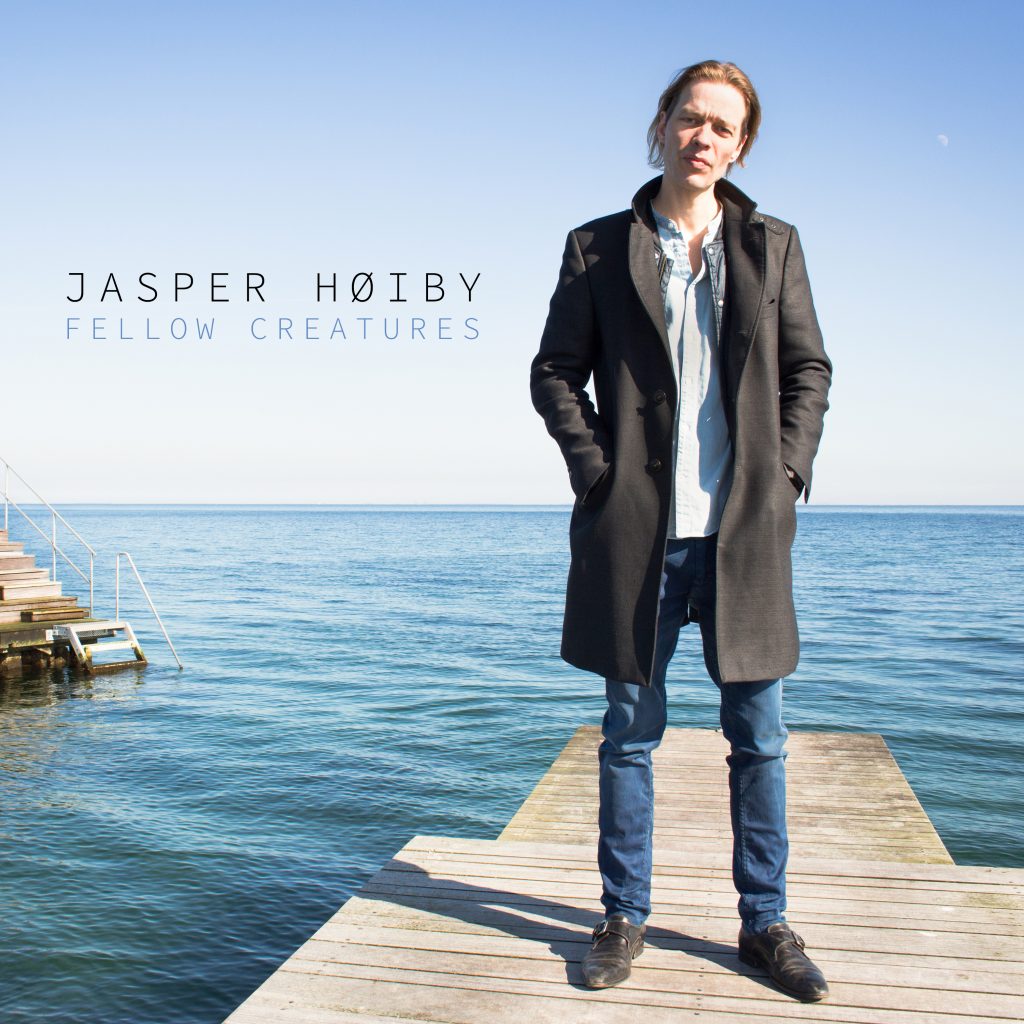

As well as Phronesis, which features British pianist Ivo Neame and Swedish/Norwegian drummer Anton Eger, current projects include MALIJA, a trio with sax player Mark Lockheart and pianist Liam Noble, an electro-acoustic duo with Brazilian multi-instrumentalist Antonio Loureiro, plus a new quintet, Fellow Creatures, with Laura Jurd (trumpet), Mark Lockheart (sax), Will Barry (piano) and Corrie Dick (drums). He returned to live in Copenhagen in 2013.

PETER QUINN: As a touring musician, what do you think the impact of Brexit might be?

JASPER HØIBY: Along with most people, I really don't know what's going to happen. It’s a little bit scary. I always thought that it'd be cool travelling around and working in this country. Since I don't live here any more it's going to be a little tricky, isn't it? I'll see what happens, it's so hard to predict. I'm going to spend as little time as possible being scared about it, but I obviously have huge concerns.  Talking of crises, your new quintet release, Fellow Creatures, is inspired in part by Naomi Klein's book This Changes Everything. You’re clearly engaged with raising people’s awareness about climate change?

Talking of crises, your new quintet release, Fellow Creatures, is inspired in part by Naomi Klein's book This Changes Everything. You’re clearly engaged with raising people’s awareness about climate change?

It's just a part of who I am, personally, that world view. I guess I'm a bit of a climate hippie, but we really need to think in those terms anyway: climate change and doing good, sustainable things with the planet. For me, it shouldn't even be a political issue. It's beyond politics, it concerns our survival. Surely we're not that stupid that we're just going to carry on going down the drain? Like Theresa May getting rid of the Climate Change Department. What's going on? It shouldn't be a political choice, no one should be allowed to do that. We've gone beyond that, we don't have time for this.

So it was important for me to try and make people a little bit aware of this, and if I can get anyone to read this book I'd be very happy. As a musician, I don't really know what else to do. I feel like I have to talk about it, because it will have a huge impact on generations to come. There was a political debate in Denmark recently – although it seemed more like people throwing mud at each other – with some people saying that artists shouldn't get involved politically. And I just think that's the biggest load of crap I've ever heard. It's our job, it's our responsibility. Not only artists, everyone should get involved. Everyone should step up and start thinking about this, as opposed to the next flat-screen TV they're going to buy. We should start realising how we're getting indoctrinated and made to buy stuff. We really should do whatever we can to break away from that, because the reality is totally different. It's not about money, it's not about immigration, it's about creating a positive change in the world.

I try and keep my ears open, all the time. I find The Zeitgeist Movement hugely interesting. One of the points about the movement is, get involved, be critical – just be critical of all the things that are presented to you as ultimate truths. Don't accept anything as a truth, try and investigate things on your own, from different perspectives. It's a very time-consuming thing to do, and it can also be very scary to do that because it challenges your world views and the world views of everyone that's been before you. We are living a lie and it's important to change our perception of things, and also realise the power we have as humans. The thing is – we have to stand together, and we have to get involved. Trusting mainstream media as our only source of truth is not enough. Another problem now is that we have so many different sources of information that people are getting drowned, and I think that's one of the ways that the establishment and mainstream media is dealing with this – flooding people with information, so that we don't have the focus and the attention span.  You've said that Fellow Creatures is a "celebration of the album as a narrative". In the age of downloading and streaming, you're still hopeful that listeners will engage with the album as a complete entity, from start to finish?

You've said that Fellow Creatures is a "celebration of the album as a narrative". In the age of downloading and streaming, you're still hopeful that listeners will engage with the album as a complete entity, from start to finish?

Well, it's like anything, isn't it? It's like reading a book – once you've tried that, you realise what a great experience it is. It's the difference between watching a film as opposed to watching a two-minute clip on YouTube. You can't compare them. And jazz music is inherently like that. You need to engage with it. Any good art form, you can't appreciate it with just a two-minute glimpse. The more you dive into it, the more it's going to give back. And that's a really important thing to think about. Culture is going to cease to exist unless we engage with it on a deeper level than we're doing at the moment.

Social media also plays a big part in this. I know I've changed. I remember when they started putting video clips on Facebook. I thought, that's a bit annoying, all these little clips. But now it's like scrolling down Facebook – it works, they did that, and now the way people consume and take in things from Facebook is through video clips. It's ridiculous. If there's too much writing or too much thought behind something, or serious discussion which tries to get a little bit deeper, you don't have the attention span for it. I even find myself going, oh this is a bit boring, and then thinking fucking hell, come on, don't be so distracted. The smart phone, the tablet, it becomes superficial on so many levels. When do you pick up the phone and call someone? When do you write a letter? Jesus Christ, people can't even write anymore. Imagine what it's going to be like down the road. This is not to say that everything's bad, there's also a lot of good things about social media and the way you can communicate with anyone from around the world. But what scares me is the way that those platforms are kind of controlling the way that we talk and discuss things. (Pictured below left: Jasper Høiby and bass. Photo by Dave Stapleton)

Compositionally speaking, what does the expanded quintet line-up allow you to achieve that you’re unable to do with Phronesis?

Compositionally speaking, what does the expanded quintet line-up allow you to achieve that you’re unable to do with Phronesis?

First of all, just having two melody lines, that's a huge opportunity. The piano just can't do that. The piano has got so many other qualities but playing a sustained melody is not one of them, at all. So that was interesting. And the blend and texture of those two sounds together, it's a bigger palette and a bigger sound. I love the trio for the fact that it can react so quickly and it can be so intuitive. I really wanted that to also be the case with the bigger band, because the more instruments you listen to, the harder it is to pay equal attention to everyone. I wanted it to be slightly more dreamy, definitely exploring more things which are out of time.

I would never read any important gig because I think it takes the attention away if you don't know it

Did you discover new things about yourself as a writer?

Always when I write I discover all the things I can't do. So it's trying to accept that as part of who you are, and also trying not to let that get in the way of where you want to go and what you want to do. But also challenge yourself to do things that you don't think you can do. I want to be able to sit down and score out something for orchestra. Also, arranging my own tunes. There's many, many things I don't feel I can do. It's even challenging for me to do two-part writing.

I was quite conscious of having the material being simple. I don't think I actually quite succeeded, but I was like, OK, I'm getting an idea now, it's in 4/4, that's not a crime. Because I've been writing lots of things in odd time signatures: 7, 5, 9, 11, 13, 15, 21, all these things. I love that, but with Ivo and Anton it's so easy to play that stuff together. It's still challenging, but... I didn't want to present new music to a new bunch of people which would be extremely hard to get to grips with. I wanted it to be simple, in terms of the basic structure, and easy to understand for them so they could express something through that. And obviously knowing their playing, some of them better than others, I kind of thought, OK, how can they fit in, what will they do really well, what's their thing that they can really add to this? It's been really fun, getting to know them. And we're still getting to know this music, and we've talked about that, too: how to really know stuff. Not only knowing it, but knowing it inside out. This stuff about never reading. I would never read any important gig because I think it takes the attention away if you don't know it. You're projecting music, you're sharing music with an audience, you want to be ready to deal with that energy that happens when you do that and not have a music stand blocking that. I was adamant that we had to do that – we're not going to get a load of time to play, I live in Denmark, they all live here, everyone's very busy. If we want to go and play somewhere, we all need to know the music so well, so we can just go and play and it'll be a pleasure and we can focus on all the musical expression and the shaping and creation of that, as opposed to playing the right dots.  Phronesis has also just released its sixth album, Parallax. With its new textures and compositional approaches, do you think the trio has more to explore?

Phronesis has also just released its sixth album, Parallax. With its new textures and compositional approaches, do you think the trio has more to explore?

Yes, I think it does, definitely. It's 10 going on 11 years now, and I think it's new in many ways. We're also, especially live, starting to explore more free things: being very flexible with tempos and changes, and going in and out of tunes from one section to another. That's really interesting and fun, and it's so easy to play with those guys, we've played so much. We can play in the dark together, we can play in the round. We're not done with that. We agreed, as well, after 10 years we had a little chat and we were like, OK, let's do another 10. The hard thing with that band now is trying to convince people that it's actually as fresh as it's ever been. And again that kind of leads us back to talking about pop culture and the way that we consume things – as soon as something is new, it seems to have more value than something's that older. And I think that's utter bullshit. Having a band which has played together for so long, if they still have fun together it's going to be so much deeper, in a way. Obviously you have fresh things happening when people meet for the first time, and there's also an energy in that.

I could spend 20 human lives studying this and I would not even be halfway there, and that's the fun thing for me

Listening to your own compositions, you're acutely aware of the primacy of rhythm – something that reaches its ne plus ultra with "Abraham's New Gift" from Alive. Where does that love of rhythm spring from?

I don't know, I've always loved rhythm. I've listened to a lot of hip hop and, even though it's more monotonous, it's very rhythmic. And also I went to an amazing school, the Royal Academy of Music, and I was exposed to a lot of different types of music and rhythms there. And obviously everything else I've listened to away from education. Rhythm has always been a massive inspiration for me. The Academy was important in exposing a lot of these kinds of musics, like world music – and I'm not an expert, it's very superficial what I know, but South American, Latin American, North and South Indian music, Middle Eastern stuff, Eastern European, African music. It's so rich and so different how all these musics are put together and where the focus is, and what the games are within the music. It's amazing, I could spend 20 human lives studying this and I would not even be halfway there, and that's the fun thing for me.

One of Phronesis's many strengths is that you have three very distinctive yet complementary compositional voices. How would you describe your respective approaches?

Although I think we're very different people and musicians, in a way we also have so many things in common. For me, it's all about the personalities, playing together. You've got to balance each other out, on a personality level, and we really do that. I see it exactly like we're set up on stage: I'm in the middle, being drawn in both directions, but also keeping things towards the middle. Anton is extremely versatile but also very accurate and dynamic. He really knows the song, all the details of it, and he can play that exactly right. But he can also do a lot of other things. And Ivo's got this very free approach, more like an outside perspective, but he can also be very direct. Actually, when they get drawn in towards the middle and try and meet each other somewhere, that's where all the magic happens – when we start to take each other's roles and play with all that. That's how I see the balance of this band working, and I remember feeling it from the very beginning. When we met and played together for the first time, it was without music. Ivo knew the music, Anton knew the music, and this was the first time we played it, and yet to me it sounded so fluent. I just had this massive grin on my face.

Having now had some time away from London, could you describe what it was like to be part of the jazz scene here?

I still feel like I'm part of the scene over here. I still feel very attached to it and involved in it on some levels. I'm a lot more integrated in this scene than I am in Denmark – people don't really know what I'm doing in Denmark, or who I am, even. And that's fine. Over here, I feel part of this. I grew up with it, musically. This is where I started my thing, and this is where I've gained all my experiences and got to play with so many great people.

I felt very free and it was very liberating to come here, to kind of start over. No-one knew who I was, not only musically but also personally. I could just come here and say, Hi, I am this person, and people would just have to accept that as being true – so I have to actually admit now I've lied all these years! At that time, musically, it was amazing to come here. It feels so much like a community. For me, as a foreigner and an outsider, I never felt like that coming here. I felt like people just opened their arms and they were, like, "welcome". And also the Academy, actually, to say some good things about that, because I know people have a lot of different opinions about it. I was in the first year of Gerard Presencer, when he was there. And he was so encouraging to me. I owe that man a lot, he was just so open-minded. I really felt like the Academy encouraged me to just be myself, musically. All the end-of-year recitals, which is kind of the big thing, the focus was on original music, do your own thing. Whenever you did it, they were like: yes, well done, great, go and do that more. I couldn't have asked for more.

I don't have a pension plan,

I don't own a house – all those things, I've said goodbye

You play all over the world at jazz clubs, festivals and concert halls, leading your own band and playing in other projects. Just how difficult is it to make a living performing this music?

It's really difficult. I think I'm probably doing better than most jazz musicians, but it's extremely challenging. There's not enough money for arts. They should be supported more. And especially now, people don't even buy CDs. It's a bit of a joke really. People say do you make a living and I'm like, yeah, well I'm still alive. I don't have a pension plan, I don't own a house – all those things, I've said goodbye, and I'm very much at ease and at peace with myself that I've done that. I don't need that. For me, it's important to do this. Obviously, I need some basics – that's partly the reason I moved back, to be close to my family and very old friends I grew up with. I actually see people more here in London now when I'm over, the good friends I want to connect with, so that's positive. But it was to secure some kind of basic living, and that's easier to do in Copenhagen for me.

There's slightly better funding there, I apply for everything I can. I was in between here: it was extremely hard with Phronesis, it's a band that doesn't belong anywhere. It's London-based, but it's not London-based. We can't get funding from anywhere. And also people think we can just do all these things and we're swimming in money from all these amazing gigs we're doing all around the world. No, no, no. The truth is very different. There was an interview recently with Linda Oh, the bass player with Pat Metheny at the moment, where she says the same things [“Almost Famous, Almost Broke: How Does a Jazz Musician Make It in New York Now?”, The Village Voice]. It's extremely difficult. And there's more and more people trying. But, you know, if it's your calling, you've gotta do it. And the only reason I'm here right now is because I didn't give up. Anyone who really wants this so much, you can't be a materialistic person, you won't get holiday, you have to think twice if you want kids – I don't have any kids. If you're fine with that, go for it, don't give up.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Album: Eve Adams - American Dust

Taking inspiration from the Californian desert

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Add comment