Vanessa Bell, Dulwich Picture Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Vanessa Bell, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Vanessa Bell, Dulwich Picture Gallery

The Bloomsbury painter whose life outshone her art

The Other Room, dating from the late 1930s, is the largest painting in Dulwich Picture Gallery's landmark retrospective, the first show to be dedicated to Vanessa Bell since a posthumous Arts Council show in 1964.

It is a quietly dazzling summary of her preoccupations as a committed, even obsessive artist. Her art was characterised by the assimilation both innocent and knowing of post-impressionism: of the sensuous use of colour, the emphasis on enigmatic emotion, the play with patterning. The red flowers in a vase, on a table placed just off-centre, anchor the whole. The woman in pink in the foreground, relaxed, in as casual and comfortable position as any graceful feline, is reading, ignoring whatever conversation might have taken place. The background of bold columns of dappled colour is a homage to abstraction. This marvellous and memorable painting (pictured below right) is an amalgam of 20th-century idioms to impressive effect.

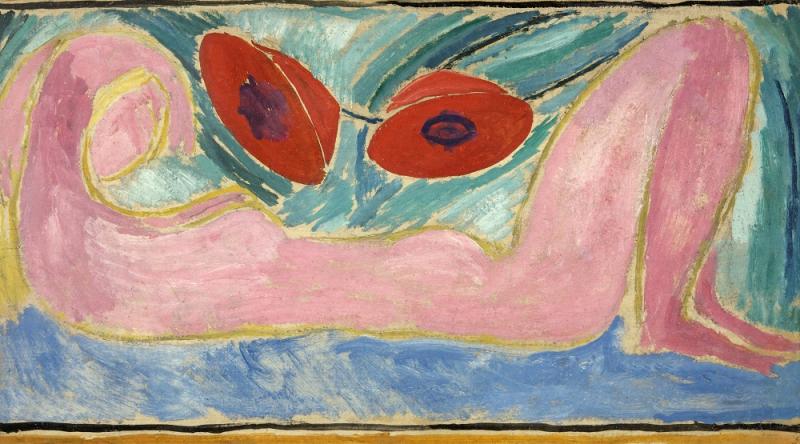

It is a startling achievement for an artist usually dismissed at best as a major minor master. She experimented with abstraction just before the First World War, abandoning it as a total idiom – although its lessons affected much of her painting – for subjects which centred on the domestic, amplified by patterns for textiles (pictured below left), firescreens and other domestic impedimenta, not to mention a fine hand with book jackets for the Hogarth Press.

It is a startling achievement for an artist usually dismissed at best as a major minor master. She experimented with abstraction just before the First World War, abandoning it as a total idiom – although its lessons affected much of her painting – for subjects which centred on the domestic, amplified by patterns for textiles (pictured below left), firescreens and other domestic impedimenta, not to mention a fine hand with book jackets for the Hogarth Press.

Born into the intellectual purple of the upper middle class, Bell spent her life at the centre of the famous, or perhaps even notorious Bloomsberries, the nickname for the most culturally influential nexus of family and friends in England in the 20th century.

Vanessa – familiarity with her life always seems to lead to using her first name – was probably its lynchpin. She was Virginia Woolf’s older, protective, sister, the stabilising core of the Bloomsbury Group, making her home at Charleston, the farmhouse near Lewes that became Bloomsbury-in-Sussex. The house was both the place and the symbol of security and safety in the course of the tempestuous lives of these families and friends, from Maynard Keynes, the most influential economist of the 20th century to Lytton Strachey who creatively sabotaged conventional biography, and E.M. Forster who appropriately valued friendship far higher than patriotism. Vanessa married the wealthy art critic Clive Bell, had an affair with Roger Fry, the most important art critic, curator and scholar of the period, and had a child with gay Duncan Grant whom she adored for the rest of her life. Her biography and her connections have almost thoroughly obscured her achievement: most of us prefer gossip to art.

It was Virginia Woolf who pointed out that “words are an impure medium, better far to have been born into the silent medium of paint”. From childhood Vanessa had wanted to be a painter, and she studied at the Royal Academy Schools where she was taught by John Singer Sargent. An accomplished, gleaming still life Iceland Poppies, 1908-1909, shows his helpful influence. The Madonna Lily, c.1915, is coarser, denser, bolder: perhaps more appealing in its very awkwardness.

It was Virginia Woolf who pointed out that “words are an impure medium, better far to have been born into the silent medium of paint”. From childhood Vanessa had wanted to be a painter, and she studied at the Royal Academy Schools where she was taught by John Singer Sargent. An accomplished, gleaming still life Iceland Poppies, 1908-1909, shows his helpful influence. The Madonna Lily, c.1915, is coarser, denser, bolder: perhaps more appealing in its very awkwardness.

She painted portraits throughout her life and it is in these studies that her gift for expressing highly emotion and tangled relationships is perhaps most visible. Lady Strachey was a highly intelligent and emotionally gifted matriarch of a large family with Anglo-Indian connections, but Bell’s 1920s portrait of this wise woman is curiously affecting and accessibly unpretentious. Several portraits of Virginia Woolf portray her complex personality through body language, the face a featureless oval suggestive of the mysterious depths of her strong, yet painfully fragile self (pictured below right). There is a witty portrait of her husband’s mistress Mary St John Hutchinson presenting her as slightly dumb and a little sly with a doughy face, yet by all accounts she was utterly charming.

Decades on, Vanessa’s portraits of herself as a septuagenarian have an aura of melancholy, of resignation, and a kind of understated grandeur too – the grandeur of survival. There are tender portraits of her children as babies and young adults, again often with just a featureless oval for the face, the character expressed by body language. The whole is introspective, often quietly celebratory of the much lived-in and loved domestic interiors. A sketch of Leonard Woolf shows him at his typewriter, the ubiquitous dog at his feet. Her subjects hint at a life well lived, full of attachment to her own world and its inhabitants.

If only that richness could have pervaded more of the paintings. For in the final analysis a unifying characteristic is a curious reticence and inhibition. The sense of effort is abundant but never seems to find that satisfying expressive energy, the fervour so characteristic of the French painters from Cézanne to Matisse that Bloomsbury so admired. Colours are often muted, the paint dry, the compositions maddeningly careful. It is as though her energies were absorbed in keeping her human cargo afloat as best she could. Her fearless embrace of the complexity of human relationships was evidenced in real life, not often enough in paint. The few outstanding paintings are tantalising in showing us what might have been. However this is the best survey we are ever likely to see, and there are rewards enough.

If only that richness could have pervaded more of the paintings. For in the final analysis a unifying characteristic is a curious reticence and inhibition. The sense of effort is abundant but never seems to find that satisfying expressive energy, the fervour so characteristic of the French painters from Cézanne to Matisse that Bloomsbury so admired. Colours are often muted, the paint dry, the compositions maddeningly careful. It is as though her energies were absorbed in keeping her human cargo afloat as best she could. Her fearless embrace of the complexity of human relationships was evidenced in real life, not often enough in paint. The few outstanding paintings are tantalising in showing us what might have been. However this is the best survey we are ever likely to see, and there are rewards enough.

The profusely illustrated book of the show is more that that: it illustrates not only a wealth of Charleston interiors and landscape, but Bloomsbury decorative arts in situ, accompanied by a host of short pithy essays on aspects of Bell’s art and life: the most readily accessible and lively publication on the artist that is available.

- Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 4 June 2017

- Vanessa Bell edited by Sarah Milroy and Ian A.C. Dejardin is published by Philip Wilson Publishers, £25

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment