Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun, National Portrait Gallery

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun, National Portrait Gallery

Gender and identity explored by artists born 70 years apart

This show of work by two artists who use photography to explore the complexities of their own identity has to be the most interesting exhibition ever staged at the National Portrait Gallery, and opening in the same week as International Women's Day couldn't be more fitting.

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun were born 70 years apart in different countries – England and France respectively – yet they share remarkably similar preoccupations. Both use the self-portrait to pose questions about what makes us who we are and to suggest that we each have multiple selves lodged within us.

Gillian Wearing is well known and having studied at Goldsmiths College and winning the Turner Prize in 1997, she enjoys international acclaim. It was her idea (since pinched by all and sundry) to photograph strangers holding up cryptic messages that indicate hidden feelings, such as “I’m desperate”.

Cahun, on the other hand, has come to light relatively recently. Although affiliated with the French Surrealists, she scarcely exhibited in her lifetime and thought of herself primarily as a writer. As a Jewish lesbian, she was a prime target for Nazi persecution so, in 1937, she left Paris with her partner and took refuge in Jersey. Many of her photographs were destroyed by the Nazis during the occupation, but after her death in 1954, those that survived began to filter into the mainstream. Each time I encounter these enigmatic self-portraits I am more enchanted by them. This quiet voice from the past turns out to be a trail blazer; as the reconsideration of identity and gender assume greater importance, her visual explorations become ever more relevant.

Cahun, on the other hand, has come to light relatively recently. Although affiliated with the French Surrealists, she scarcely exhibited in her lifetime and thought of herself primarily as a writer. As a Jewish lesbian, she was a prime target for Nazi persecution so, in 1937, she left Paris with her partner and took refuge in Jersey. Many of her photographs were destroyed by the Nazis during the occupation, but after her death in 1954, those that survived began to filter into the mainstream. Each time I encounter these enigmatic self-portraits I am more enchanted by them. This quiet voice from the past turns out to be a trail blazer; as the reconsideration of identity and gender assume greater importance, her visual explorations become ever more relevant.

Described by André Breton as ”one of the most curious spirits of our time”, Cahun considered gender to be fluid and negotiable. “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation”, she wrote. “Neuter is the only gender that suits me.” She swapped her given name, Lucy Schwob for something more ambiguous and, shaving off her hair, photographed herself as a man in a suit and tie (pictured above right: Self-Portrait (as a Dandy, Head and Shoulders), 1921-22); but with doll-like make-up and a halo of blonde plaits, she also becomes Bluebeard’s wife, Elle in a long dress.

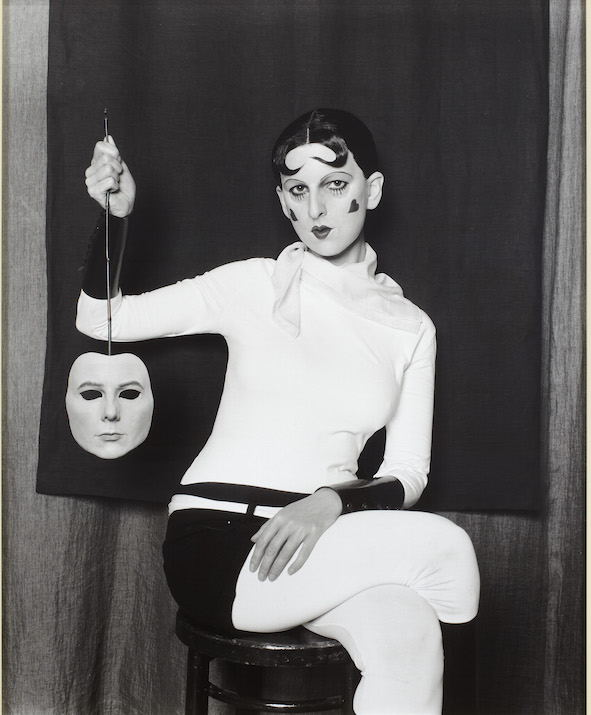

Most of her self-portraits are androgynous, though. Sitting crossed legged like a Buddha, she wears a satin shift and skull cap, with multiple strings of pearls around her neck; wearing aviator’s goggles, she sports close-cropped hair and glossy lipstick. One shot shows her floating naked in a rock pool like a water nymph, while in a photo from 1919, her monk-like profile echoes a portrait of her father whom she closely resembles. In a bizarre series from 1927 titled I’m in Training Don’t Kiss Me, she poses as a strong man with dumb bells, yet has two kiss curls on her forehead and a heart painted on each cheek.

Most of her self-portraits are androgynous, though. Sitting crossed legged like a Buddha, she wears a satin shift and skull cap, with multiple strings of pearls around her neck; wearing aviator’s goggles, she sports close-cropped hair and glossy lipstick. One shot shows her floating naked in a rock pool like a water nymph, while in a photo from 1919, her monk-like profile echoes a portrait of her father whom she closely resembles. In a bizarre series from 1927 titled I’m in Training Don’t Kiss Me, she poses as a strong man with dumb bells, yet has two kiss curls on her forehead and a heart painted on each cheek.

In homage to Cahun, whom she discovered in the mid Nineties, Wearing re-enacted one of the series in 2012 (pictured above left: Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face, 2012). Her imitation is so convincing that it takes a while to decode the image. Dressed in identical clothing, she sits in the same position. A mask modelled on Cahun’s self-portrait covers her face while, in place of the dumb bells, she holds up a mask of her own face. Its as though to become Cahun, she has had to peel away her own identity which now dangles from her hand like a memento mori of her former self.

Its not the only time Wearing has portrayed herself as an empty shell. Titled Me as Mask, a sculpture from 2013 (pictured below right) shows her as nothing more than an elegant hand holding a mask of her face. So who is Gillian Wearing? Its a question that she also asks. “Where am I in this ?’ she enquires. “How can you know me or her (Cahun)? How can we ever know ourselves?”

Whereas Cahun transformed herself for the camera with make-up, clothing and props, Wearing uses masks to assume her own and other people’s identities. In Self-Portrait, 2000, the rigid contours of the plastic mask over her face make her look like a robot. By 2011 the technology had improved so much that the mask she wears in another self-portrait resembles flesh, the only clue as to its presence being the cut-outs round her eyes (pictured below left: Self-Portrait of Me Now in a Mask, 2011).

Whereas Cahun transformed herself for the camera with make-up, clothing and props, Wearing uses masks to assume her own and other people’s identities. In Self-Portrait, 2000, the rigid contours of the plastic mask over her face make her look like a robot. By 2011 the technology had improved so much that the mask she wears in another self-portrait resembles flesh, the only clue as to its presence being the cut-outs round her eyes (pictured below left: Self-Portrait of Me Now in a Mask, 2011).

In 2003 she began creating a family album based on old photos of her grandparents, parents, brother, sister and even her 3 year old self. Made from silicone by professionals, the masks are all-but invisible and Wearing has become so expert at imitating the posture, gesture and clothing of people of different ages and sexes that she manages to pass convincingly as her various relatives and, even more uncannily, as her toddler self.

This would be no more than clever masquerade if it didn’t invite us to consider the role played by genetics in determining who we are along with factors such as gender, class, education, opportunity and happenstance. The most moving of these family portraits is a video of Wearing as her elderly grandmother, slumped immobile in a wheelchair. To adopt the persona of this dying woman required her not only to experience the indignity of old age but also to embrace her own mortality, as well as that of a loved one.

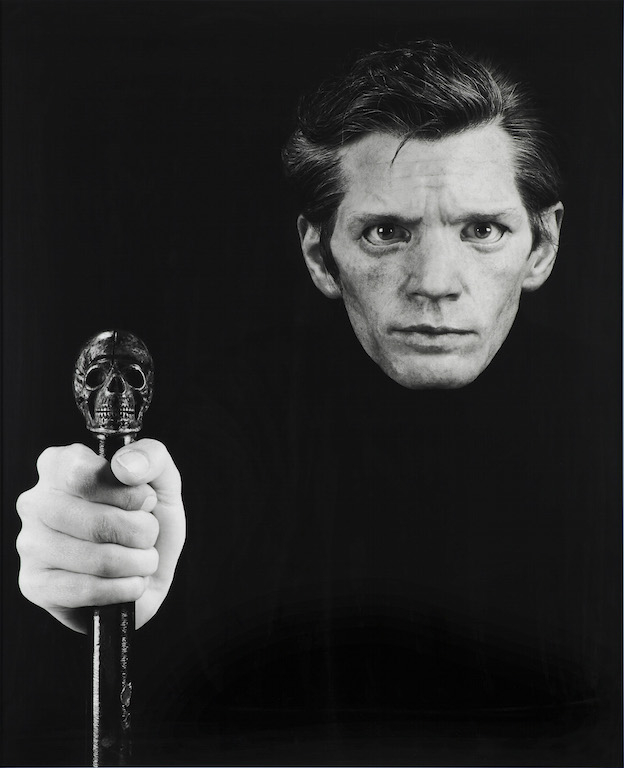

Wearing has also created a gallery of her spiritual family, artists whom she admires including Andy Warhol and Diane Arbus. Most compelling is her recreation of a self-portrait made by Robert Mapplethorpe shortly before he died of AIDS in 1989 (pictured below right). His gaunt face echoes the skull on top of the cane, which he clutches provocatively as a sign of his present infirmity and his impending death. His face may already resemble a death mask, but his eyes bore into you with incredible intensity. “I had to ensure my eyes held the same psychological expression as his”, Wearing recalls: “a look of inner turbulence but very much alive. We all have masks and behind someone’s mask is always a torrent of conflicting emotions and thoughts.”

Rock n’ Roll 70, 2015 is a new departure. The 52-year-old artist appears unmasked alongside a computer-generated image of herself at 70 plus a space for an actual photograph of herself if she reaches 70. Covering the end wall is Rock n’ Roll 70 Wallpaper (main picture: detail), a bank of images of potential future selves created with the help of forensic experts; depending on hair style, facial expression, surgical intervention, body shape and dress, these vary from dowdy matron and smiling homebody to wrinkled neurotic, bright-eyed intellectual and confident fashionista.

For me, this is the most courageous and interesting of Wearing’s projects, since it requires an unnerving degree of introspection and a much greater willingness to make herself vulnerable than does her chameleon-like gift for impersonating other people.

For me, this is the most courageous and interesting of Wearing’s projects, since it requires an unnerving degree of introspection and a much greater willingness to make herself vulnerable than does her chameleon-like gift for impersonating other people.

The dialogue established between the two artists in this superb exhibition highlights the differences in their approach to the exploration of identity. Cahun focuses on the many personas lodged within her, while in mimicking the appearance of others, Wearing invites us to question what we can know about anyone from the messages they transmit about themselves. In each case, though, the relationship between the surface and someone’s interior world is revealed to be complex, intricate, volatile and endlessly fascinating.

- Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the Mask, Another Mask at the National Portrait Gallery until 29 May

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment