Queer British Art 1861-1967, Tate Britain | reviews, news & interviews

Queer British Art 1861-1967, Tate Britain

Queer British Art 1861-1967, Tate Britain

A vital selective history in images, but is much of it great art - and does it matter?

"Good for the history of music, but not for music," one of Prokofiev's professors at the St Petersburg Conservatoire used to say of artistically dubious works which created a splash, according to the composer's diaries.

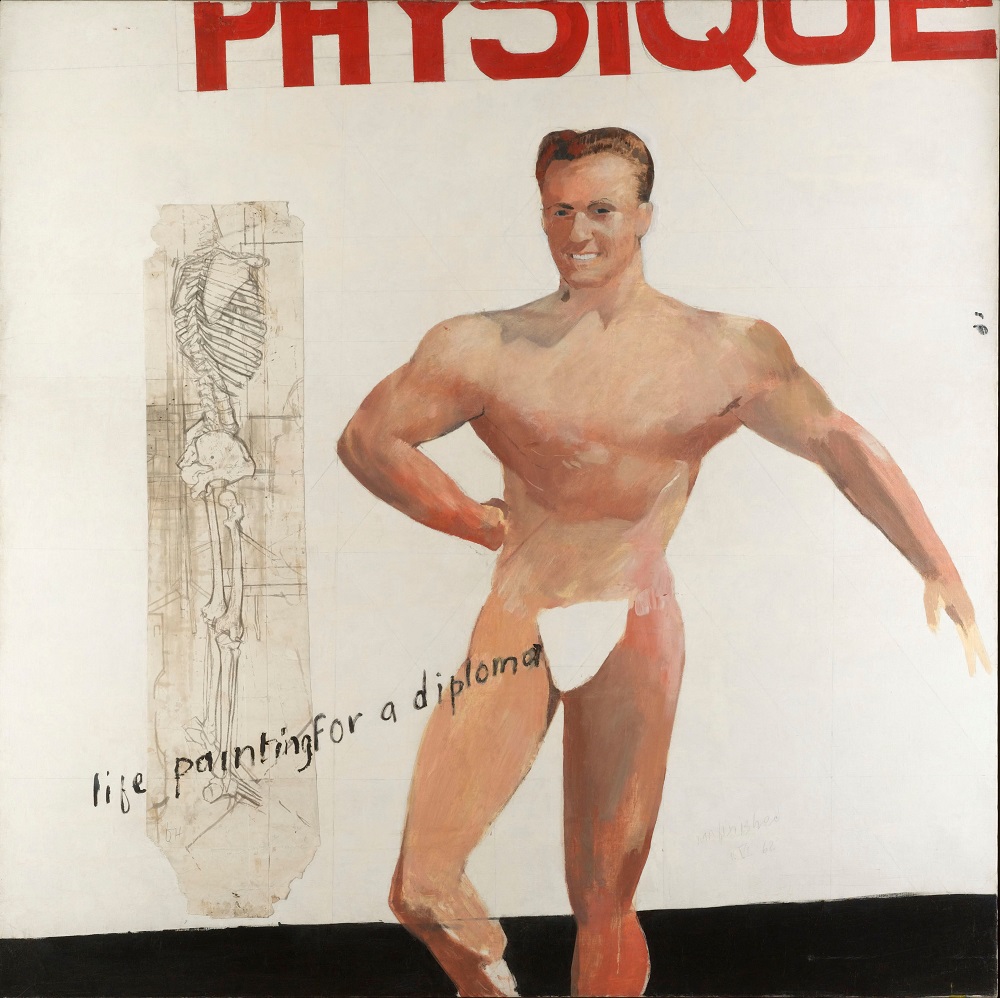

The dates are crucial: 1861, the starting point, was when the Offences Against the Person Act saw the abolition of the death penalty for sodomy, and in 1967 the Sexual Offences Act partly decriminalised acts between consenting adults in private and set the age of consent in England and Wales at 21. What it means in effect is a dreadful start to the exhibition and a reasonably flamboyant ending. Victorian ambiguities are represented by bad art: Simeon Solomon may have inspired a wonderful play by Neil Bartlett, A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep, but I wouldn't give house room to his stuff in a first room noteworthy only for two of Wilhelm von Gloeden's more decorous Italian boys, and perhaps Henry Scott Tuke's studies of young male nudes, one of the few points in the show where we come close to anything that might be described as erotic. At the other end, there are two Hockneys representative of his early style – the most famous one, We Two Boys Together Clinging, 1961, is in the exhibition down the way in the same building – and two Bacons, of which the portrait putatively of his lover George Dyer is the more typical. Hockney's uncharacteristic Royal Academy diploma entry (pictured above, © Yageo Foundation) cues a case of muscle magazines in the centre of the room. Runners-up in several ways throughout the previous galleries include the celebrated library-book jackets reworked by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell – I wasn't the only one laughing out loud at the budgie on the front of The World of Paul Slickey or "Fucked by Monty" as one of the new titles for works by Emlyn Williams. In the pencilled comments displayed in the final room, someone has asked when the Tate will be giving full shows to Keith Vaughan and Edward Burra. I heartily concur in the latter's case: the two canvases on display, Izzy Orts and Soldiers at Rye, are among the few absolute highlights of the exhibition.

At the other end, there are two Hockneys representative of his early style – the most famous one, We Two Boys Together Clinging, 1961, is in the exhibition down the way in the same building – and two Bacons, of which the portrait putatively of his lover George Dyer is the more typical. Hockney's uncharacteristic Royal Academy diploma entry (pictured above, © Yageo Foundation) cues a case of muscle magazines in the centre of the room. Runners-up in several ways throughout the previous galleries include the celebrated library-book jackets reworked by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell – I wasn't the only one laughing out loud at the budgie on the front of The World of Paul Slickey or "Fucked by Monty" as one of the new titles for works by Emlyn Williams. In the pencilled comments displayed in the final room, someone has asked when the Tate will be giving full shows to Keith Vaughan and Edward Burra. I heartily concur in the latter's case: the two canvases on display, Izzy Orts and Soldiers at Rye, are among the few absolute highlights of the exhibition.

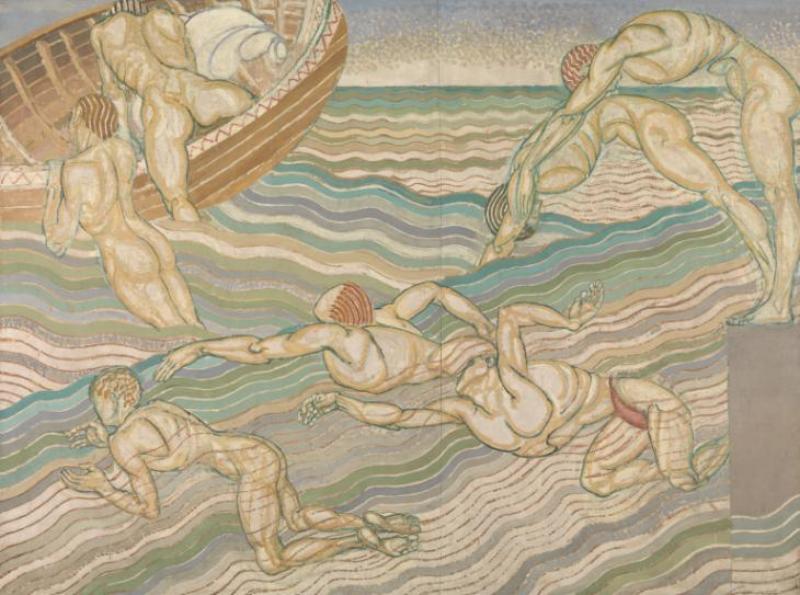

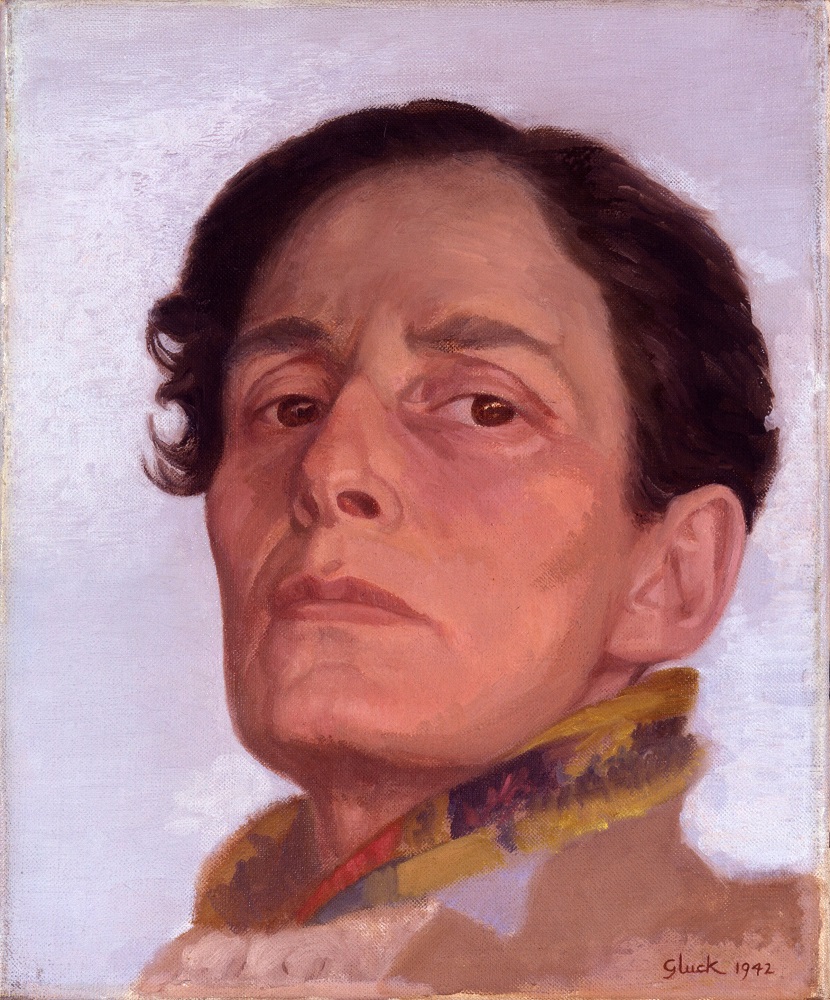

Another comment asks "Where are the women? 10 per cent is not enough". There must be more than 10 per cent, and it's largely on display in Rooms Four and Five, after which what used, appallingly, to be called "the distaff side" more or less disappears. Dame Ethel Walker's large canvas of classical female nudes and semi-nudes The Excursion of Nausicaa, 1920, balances Duncan Grant's bathing boys deemed too "degenerative" a theme for its intended destination, Borough Polytechnic. Portraits of strong women abound – Gluck's self-portrait, used as the poster image (pictured above, © National Portrait Gallery), William Strang's Vita Sackville-West, a much needed dash of vibrant colour, and those of Dame Laura Knight. To my mind the finest portrait of all is Dora Carrington's of Lytton Strachey.

Another comment asks "Where are the women? 10 per cent is not enough". There must be more than 10 per cent, and it's largely on display in Rooms Four and Five, after which what used, appallingly, to be called "the distaff side" more or less disappears. Dame Ethel Walker's large canvas of classical female nudes and semi-nudes The Excursion of Nausicaa, 1920, balances Duncan Grant's bathing boys deemed too "degenerative" a theme for its intended destination, Borough Polytechnic. Portraits of strong women abound – Gluck's self-portrait, used as the poster image (pictured above, © National Portrait Gallery), William Strang's Vita Sackville-West, a much needed dash of vibrant colour, and those of Dame Laura Knight. To my mind the finest portrait of all is Dora Carrington's of Lytton Strachey.

Una Troubridge, who as Radclyffe Hall's partner was once described as "the bucket in the well of loneliness", surprises with an arresting 1912 plaster bust of Nijinsky as the protagonist in his Ballets Russes choreography of Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune. In these galleries of entertainers and worthies, the historical memento can be more powerful than the portrait – Noel Coward's dressing gown, the prison door from Reading Gaol reputedly that of Oscar Wilde's cell, which looks like a work of art alongside his portrait.

Fortunately photographs by Angus McBean keep hold of the artistic ideal (one which appears much later, his study of Quentin Crisp pictured left, © Estate of Angus McBean/National Portrait Gallery, is perhaps the best of all) – though for a more adventurous photographic aesthetic, you might well be impressed by the surrealist work of Claude Cahun, a startling intrusion among the paintings of Room Five.

Fortunately photographs by Angus McBean keep hold of the artistic ideal (one which appears much later, his study of Quentin Crisp pictured left, © Estate of Angus McBean/National Portrait Gallery, is perhaps the best of all) – though for a more adventurous photographic aesthetic, you might well be impressed by the surrealist work of Claude Cahun, a startling intrusion among the paintings of Room Five.

Here, and throughout, you'll be studying the captions sometimes more carefully than the art, and occasionally more incredulously (could "Michael Field" really be the composite of an aunt and niece who became an item? That gives a kick beyond the Bloomsbury triangles to come). Ultimately, it doesn’t matter too much what Queer British Art really is, or how much the label comes to reassess past fluidities with present certainties. The main thing is that you’ll take away a few surprises, perhaps even revelations. And yes, as those comments at the end reveal, heterosexuals enjoy the show as well.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment