Jonathan Biss, Milton Court | reviews, news & interviews

Jonathan Biss, Milton Court

Jonathan Biss, Milton Court

Intellectual rigour guides a range of last thoughts, but the hall is forbidding

"Late Style", the theme and title of pianist Jonathan Biss's three-concert miniseries, need not be synonymous with terminal thoughts of death.

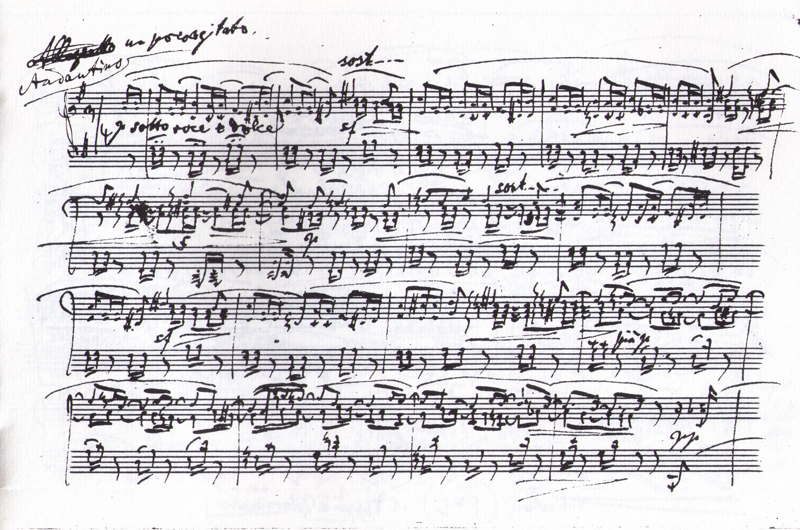

Not that Biss is a playful or fantastical pianist. On this evidence, at least, unsentimental firmness of purpose is his forte, and the second half of the programme, all Brahms, brought out the best in him (and the audience, perhaps, once it had adjusted to the plummy middle register which can surely, again, be blamed on the venue). Earlier, he'd spoken eloquently about why he wanted to preface the two last sets of piano pieces with the Andante espressivo of Brahms's Op. 5 Piano Sonata, its serene twilight chains of thirds contrasting with the more troubling ones of Op. 119's B minor Intermezzo. As a convenient diversion in between came the surprise last stage of the slow movement, a new and noble idea which Wagner surely adapted for the horn-throbbing coda of Hans Sachs's Act Two monologue in Die Meistersinger. By reversing the two sets - it's difficult to say when the actual pieces actually originated, but their order in each group should be unassailable - Biss left us not with the Pyrrhic victory of Op. 119's initially stout and steaky E flat Rhapsody but with the E flat minor blackness of Op. 118's obsessive finale. Along the way we heard all the necessary enigmatic beauty of the quieter numbers (pictured above: manuscript of the sotto voce Op. 119 No. 2), but with Brahms's meditation around the Dies Irae, that Latin chant for the dead which his natural successor Rachmaninov was to take up so relentlessly, the coffin lid slammed shut.

By reversing the two sets - it's difficult to say when the actual pieces actually originated, but their order in each group should be unassailable - Biss left us not with the Pyrrhic victory of Op. 119's initially stout and steaky E flat Rhapsody but with the E flat minor blackness of Op. 118's obsessive finale. Along the way we heard all the necessary enigmatic beauty of the quieter numbers (pictured above: manuscript of the sotto voce Op. 119 No. 2), but with Brahms's meditation around the Dies Irae, that Latin chant for the dead which his natural successor Rachmaninov was to take up so relentlessly, the coffin lid slammed shut.

Fortunately Biss opened it again by finding the end in the beginning, an encore reprise of the calm, chordal beauty in the first of Schumann's Gesänge der Frühe (Songs of Early Morning). Its opening context promised so well, but the Milton Court boominess soon set in with the second and third pieces, and conspired with Biss's fondness for the sustaining pedal in a conclusion to the Chopin which sounded not so much muddy as under water.

The echo-effect worked to Biss's advantage in the single lines of excerpts from György Kurtág's Játékok (Games), an ongoing series of "pedagogical studies", late but not last from the ever-fertile Hungarian. The selection eschewed humour, not a quality apparent anywhere in the concert, even in "Fugitive thoughts about the Alberti bass", but proved undeniably haunting. When the notes are stripped away, the venue can work to the soloist's advantage, but pianists beware: you'd be better off searching out the warmer if ruthlessly exposing acoustics of Kings Place's far lovelier concert hall.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment