'The challenge is to make something of not very much': Iestyn Davies on Britten's Oberon | reviews, news & interviews

'The challenge is to make something of not very much': Iestyn Davies on Britten's Oberon

'The challenge is to make something of not very much': Iestyn Davies on Britten's Oberon

The countertenor, singing the Fairy King at Aldeburgh, traces the role's history

Tomorrow Britten’s opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream will begin a short run at the Snape Maltings, Suffolk in a new production directed by Netia Jones and conducted by Ryan Wigglesworth. It will mark the high point of the Aldeburgh Festival’s summer celebrations half a century on from the opening of the Snape Maltings concert hall.

I shall be performing the countertenor role of Oberon. Alongside me will be soprano Sophie Bevan as Tytania, bass Matthew Rose as Bottom, a troupe of seasoned rustics, a quartet of nubile lovers watched over by a stiff royal duo, one acrobatic Puck and the boys of Chelmsford Cathedral choir as the fairy charges. It’s safe to say there is something for everyone and Netia Jones’ setting will play heavily on her characteristic style of detailed yet striking costumes overlaid by beautiful, vast projections across the stage. It will be a world of reflections, shadows and blurred lines, embedded in the natural world and the herbalists of Elizabethan history. The human characters will chronicle the community of those associated with the Maltings itself and the Fairies will in some way bridge the two.

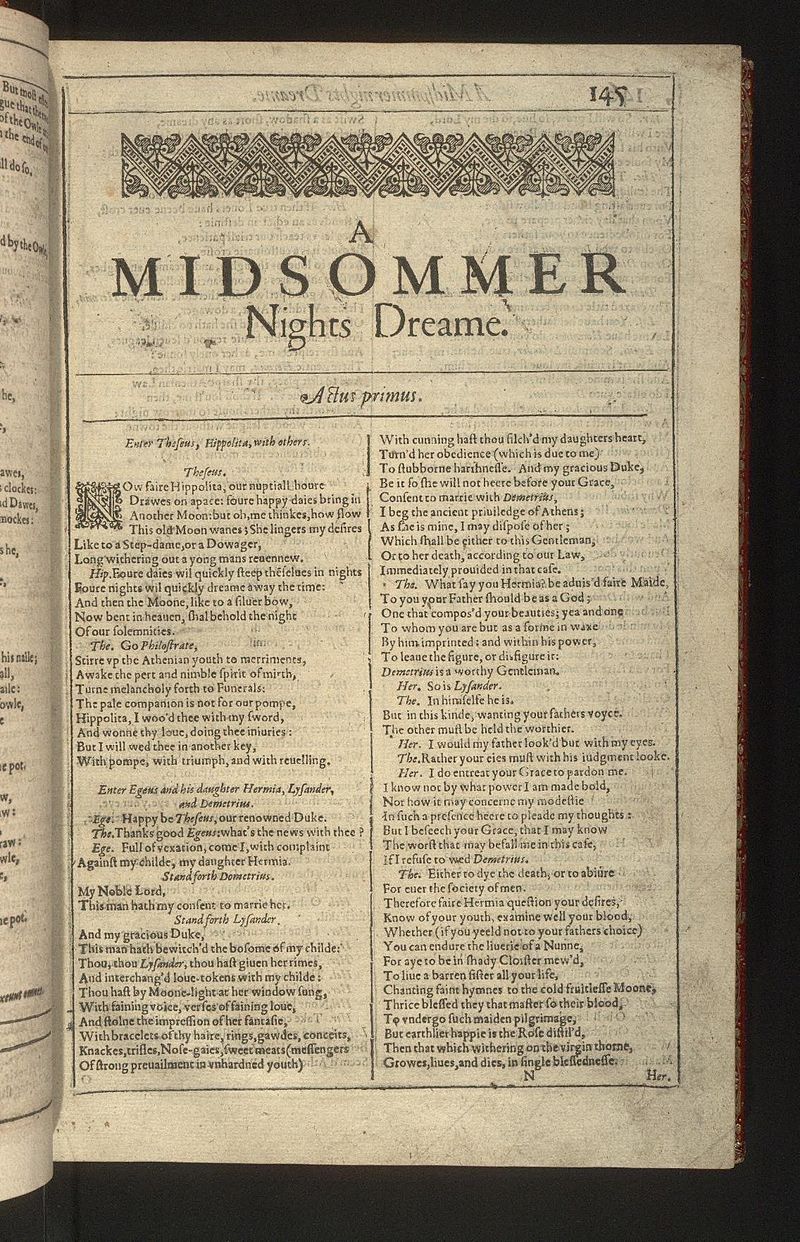

Shakespeare virtually invented the "Fairy", or our notion of what fairies are. Up until that time there was no agreed consensus on what we now recognise as bewinged beings fluttering about toad-stools at the bottom of our garden. Britten took this idea one step further in casting the King of the Fairies, Oberon, as a countertenor. It was a radical decision. As far as we know, before 1960 when Dream was premiered, a countertenor had never played a part in an opera. In the eighteenth century and before there may have been roles sung by countertenors but we don’t have specific or conclusive evidence that this voice type was what we think of it today. Certainly, like Shakespeare, Britten’s imagination translated something unheard of in living memory into a reality: the operatic countertenor.

Shakespeare virtually invented the "Fairy", or our notion of what fairies are. Up until that time there was no agreed consensus on what we now recognise as bewinged beings fluttering about toad-stools at the bottom of our garden. Britten took this idea one step further in casting the King of the Fairies, Oberon, as a countertenor. It was a radical decision. As far as we know, before 1960 when Dream was premiered, a countertenor had never played a part in an opera. In the eighteenth century and before there may have been roles sung by countertenors but we don’t have specific or conclusive evidence that this voice type was what we think of it today. Certainly, like Shakespeare, Britten’s imagination translated something unheard of in living memory into a reality: the operatic countertenor.

The countertenor in question was Alfred Deller and the rest, as they say,is history. Or is it? Deller’s incarnation as Oberon has traditionally been described as a revolutionary milestone, facilitating the career paths of future countertenors. But could one equally argue that Britten’s creation drew problems of its own making and in turn has proved something of a curate’s egg? I don’t particularly fall in either camp, but I feel strongly about both and it is only through playing the role myself a number of times that I have been drawn to investigate this a little further.

Britten had decided to cast Oberon as a countertenor because (as he wrote to Deller), "I see you and hear your voice very clearly in this part". Unlike today, there wasn’t a wide choice of countertenors on the professional scene so Britten composed primarily with Alfred Deller in mind. In the 1720s the castrato Senesino was likewise a muse for Handel. Deller (pictured below in the premiere with Jennifer Vyvyan as Tytania), though shocked to be offered the role, accepted but made clear that the composer should be aware of his comfortable vocal range of an eleventh. Looking at the score this range sits from a bottom G (below middle C) to a top C (an octave above middle C). Within this compass the majority of what is sung lies in the middle between middle C and the A, a sixth above it. But there are significant patches of phrasing and text that hover at the lower end of the eleventh, something that proves uncomfortable reading for the young student countertenor browsing prospective roles.

The falsetto voice is crudely described as the sound produced when air passes through the open vocal cords, vibrating only the very edges of their vocal folds. Too much breath, too fast a release of air or too little or too slow a release and this vocal tightrope can fail in an instant. For that reason, the low end of the voice, when the cords and the air pressure are approaching the finest measures of relaxation, can often misbehave. The danger at the low end of the range is for the falsetto to "split" into the modal chest voice, producing a sort of teenage yodel. So the complaint therefore of many countertenors today is that the role is simply "too low".

A modern countertenor, moreover, is encouraged to sing a much wider repertoire of operatic roles than those of Deller’s generation. Not only the higher-lying Handel roles, but also Mozart, Rossini and Johann Strauss II have joined the roster. Countertenors today are trending higher and higher. Added to this, the traditional route from choir stalls to concert platform that has proved the fashion in the United Kingdom for the last 70 years is fast becoming supplanted by a more conservatoire based journey, meaning that young countertenors are not necessarily starting out, as you would in a choir, being the "second line down", but rather the only line, the soloist, the high voiced male counterpart to the mezzo-soprano. Deller began singing in choirs and in asking for the role of Oberon to be set within a compass of a comfortable eleventh he was in effect outlining the job requirement of any cathedral countertenor for the past 500 years.

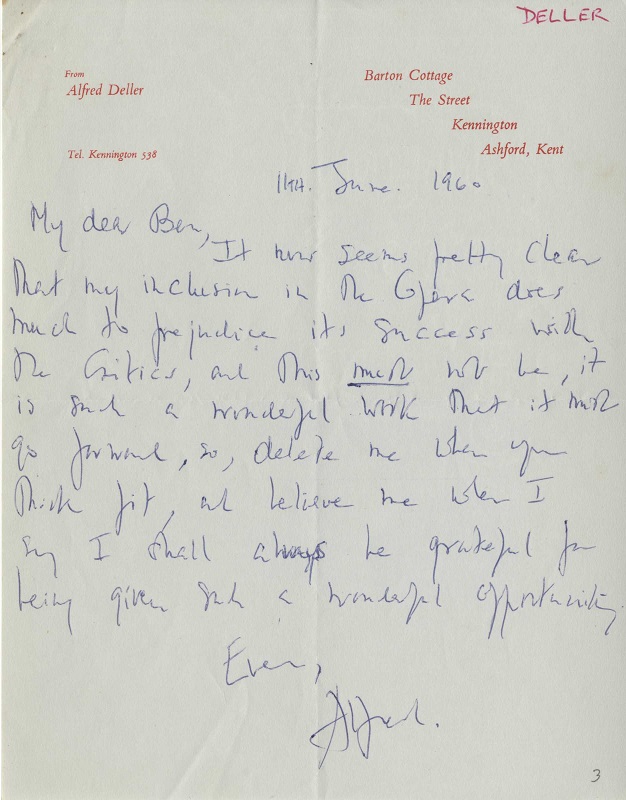

It was therefore with a sense of trepidation that Deller became Oberon, for he admitted to Britten a limitation in his own dramatic capabilities. With barely any stage experience and possessing a statuesque figure, he worried that on the tiny stage of the Jubilee Hall he would be at a loss how to play Oberon [he also worried about the critical reception, asking Britten to "delete me when you think fit", letter pictured left, courtesy of the Britten/Pears Estate; the answer was wise and reassuring]. Britten reassured him that he wouldn’t be required to do much acting and in fact he had imagined the role as a being invested with Prospero-like dignity. Deller’s foreboding proved well founded if we take history at its word. Early critical reports of Dream persuaded Deller to proffer his resignation from the production before it opened in order not to damage what was as he saw it an otherwise successful production. But, perhaps this was just a neurotic singer misguidedly reading his own reviews, reviews that after all announced, "a countertenor Oberon is no obstacle nowadays".

It was therefore with a sense of trepidation that Deller became Oberon, for he admitted to Britten a limitation in his own dramatic capabilities. With barely any stage experience and possessing a statuesque figure, he worried that on the tiny stage of the Jubilee Hall he would be at a loss how to play Oberon [he also worried about the critical reception, asking Britten to "delete me when you think fit", letter pictured left, courtesy of the Britten/Pears Estate; the answer was wise and reassuring]. Britten reassured him that he wouldn’t be required to do much acting and in fact he had imagined the role as a being invested with Prospero-like dignity. Deller’s foreboding proved well founded if we take history at its word. Early critical reports of Dream persuaded Deller to proffer his resignation from the production before it opened in order not to damage what was as he saw it an otherwise successful production. But, perhaps this was just a neurotic singer misguidedly reading his own reviews, reviews that after all announced, "a countertenor Oberon is no obstacle nowadays".

Indeed, despite his own acting ability Deller was at the mercy of a role whose music was itself quite immobile. Only the famous setting of "I know a bank where the wild thyme blows" offers an opportunity for creative interpretation that might inform the characterisation beyond the dignified. Yet even here, it is the stillness and antiquated decoration of this Purcellian homage that dominates, persuading the singer to deliver with an almost stately bearing. There are of course moments of exquisite beauty in the opera when Oberon does sing, but it is my impression that they played inevitably to the strengths (and weaknesses) that Britten regarded in Alfred Deller.

It is well known that when the opera was revived in the 1967 production at Aldeburgh, James Bowman, then the new kid on the block, made enough of an impression to persuade Britten to consider developing the role, as he could see the wider range of dramatic qualities that Bowman’s voice and stage personality brought to the role. This never came to pass though it illustrates that whilst Deller may have been the source of inspiration for the composition it was ultimately Britten, not Deller, who was responsible for any apparent limitations in its style and delivery.

In my own experience of playing the role of Oberon [pictured above by Marty Sohl: Davies in the role at the Metropolitan Opera], only once have I felt that the character was allowed to explore beyond the boundaries implied by the music. One production for example permitted Oberon to stay stock still on a flying platform, unable do much beyond two-dimensional movement. Another relied on the brilliance and vivid colour of the costumes to act as dressing for an otherwise traditional delivery. Without argument these particular productions responded to the music when it came to Oberon; ethereal beauty and quiet stillness implied the ambiguous mix of malevolence and benevolence. It was as if they dared not challenge Britten’s specific interpretation. I always feel that in Shakespeare in particular we need to respond to the text first. Therein lie the clues. Nevertheless in a composer, we have both editor and director and it seems Britten was destined to make Oberon nothing more than dignified and politely sinister.

When a director gives you licence to explore the role without necessarily just responding to the musical gesture it can be hugely liberating. Chris Alden’s 2011 production at ENO did just that [Davies pictured below by Alastair Muir with Anna Christy as Tytania]. Like it or loathe it, the school setting in which Oberon was characterised as the type of master with slightly too much interest in the boys’ development imposed a new colour to the music that I hadn’t heard before and that perhaps was only possible by coming at the opera from a new dramatic perspective. The claustrophobia of academic corridors and all-pervading hierarchy within a school lent the score a darkness and sense of doom that I had only heard explicitly in the second half of Britten’s last opera Death in Venice. The reaction was mixed. Inevitably many complaints were that it would have "upset Ben". I wanted to holler back, "What about Shakespeare?!"

We are as performers, actors and directors subservient to the composer, but that does not mean that every composer discourages experimentation and interpretation and at this time opera houses across the world are enjoying productions from directors who are not afraid to approach major works armed to the teeth with the tools and traits of straight theatre.

But is there a halfway house? Did Deller and Britten actually hit upon something that was limiting and yet radical which we should celebrate for its naked simplicity? This would in turn allow the theatre of the mind, the most powerful tool at a singer’s disposal to be the driving energy force behind the text, music and their delivery. Surely in playing Shakespeare any singer would heed the advice of Hamlet to the players: "Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly on the tongue […] Nor do not saw the air too much with your hand […] suit the action to the word, the word to the action."

In Netia Jones’ new production at Snape I have found myself having to rethink the physicality of Oberon. Netia finds the malevolence in Oberon through the calculated and protracted movement he makes. Make fast or jerky reactions and he loses that power and she argues he becomes more human. I have found that in obeying this as best I can the onus then falls more squarely on me to use the Shakespearean text than react to Britten’s music. In turn I need to up the stakes of the textual meaning and delivery to compensate for the theatrical urge to be "natural" or "real" A great deal of what we are doing on stage is enhanced by Jones’ alluring and beguiling projections that lie over us like the very veil of sleep so central to the play; thus we are not fully aware of the stage picture that the audience will enjoy. It’s a lesson in trusting a director and having faith in an other’s vision. Moreover, it reinstalls faith in the Britten/Deller concoction.

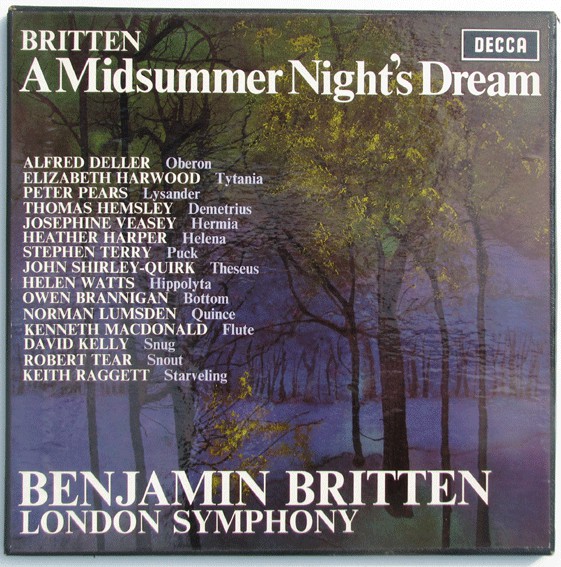

For after Deller there came a succession of odd choices; a tenor sang the role at the German premier in 1961, later at the Komische Oper Oberon was given to a bass and at the Russian premiere in 1965 it was sung by mezzo-soprano Elena Obraztsova. None of these had anything to do with Britten. Whilst an American countertenor, the late Russell Oberlin, sang the role in the meantime at Covent Garden it was to Deller that the composer returned in the 1966 Decca recording. Clearly it was, until the following year, Alfred Deller and his unique voice on which Britten was stuck. I don’t believe therefore that we should in anyway downplay the awkwardness of the 1960 premiere; it should rather be celebrated as a necessarily difficult birth. Instead of thinking of Deller as a paranoid actor and Britten as a charitable composer, I’d like to argue that the whole is very much greater than the sum of its parts. Oberon in Britten’s Dream is evidence of this synergy.

For after Deller there came a succession of odd choices; a tenor sang the role at the German premier in 1961, later at the Komische Oper Oberon was given to a bass and at the Russian premiere in 1965 it was sung by mezzo-soprano Elena Obraztsova. None of these had anything to do with Britten. Whilst an American countertenor, the late Russell Oberlin, sang the role in the meantime at Covent Garden it was to Deller that the composer returned in the 1966 Decca recording. Clearly it was, until the following year, Alfred Deller and his unique voice on which Britten was stuck. I don’t believe therefore that we should in anyway downplay the awkwardness of the 1960 premiere; it should rather be celebrated as a necessarily difficult birth. Instead of thinking of Deller as a paranoid actor and Britten as a charitable composer, I’d like to argue that the whole is very much greater than the sum of its parts. Oberon in Britten’s Dream is evidence of this synergy.

The list of countertenors since Deller to have sung and played Oberon is growing ever larger; James Bowman, Michael Chance, Robin Blaze, Brian Asawa, David Daniels, Larry Zazzo, Bejun Mehta, Tim Mead and James Laing to name but a handful. Every one of them has brought his own personality and vocal ability to bear and each performance differs because of this. Certainly without Oberon who is to say what direction the countertenor voice would have headed?

In the 18th century the castrati were easily replaced by women and later on such heroic roles became the property of tenors and baritones. The countertenor, without Britten, was looking at a future of lute songs and the occasional oratorio. Therefore the presence of Deller vibrates through every note of Oberon’s music. The sense of his unique voice and artistry pervades each utterance. The very fact that there is a sense of limitation and concentrated minimalism to Oberon is the very thing that makes it such a challenge. The challenge is to make something of not very much and to make not very much of the challenge. In doing so we will always get closer to what Britten heard. Never before has the phrase "less is more" chimed with such harmony. I look forward to this challenge being met by countertenors for at least another 50 years.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Add comment