Whitney: Can I Be Me review - tragic account of superstar who fell to earth | reviews, news & interviews

Whitney: Can I Be Me review - tragic account of superstar who fell to earth

Whitney: Can I Be Me review - tragic account of superstar who fell to earth

How did it go so wrong for pop's most glamorous diva? Nick Broomfield investigates

The statistics of Whitney Houston’s career are flabbergasting in this post-CD era. Her 1985 debut album sold 25 million copies. “I Will Always Love You” is the best-selling single by a female artist in music biz history. Its parent album, the soundtrack to The Bodyguard, sold more than one million copies in a week. She had more consecutive Number One hits than The Beatles.

But, as Nick Broomfield’s new documentary reveals, none of this could protect her from a grasping family, parasitic hangers-on, and an unfaithful husband who aided and abetted her use of drugs and alcohol. The worst of it was that when Houston was found dead in her bathroom of the Beverly Hilton hotel in February 2012, several friends and members of her entourage had seen the terrible event coming for some time.

How could a global megastar once worth $250 million fall so far? Anyone who saw Whitney in her regal prime could hardly fail to marvel at her poise, her effortless command of the stage, and her voice, which could capture the finest musical nuances or let fly with a huge, concentrated tone capable of blowing the lid off Madison Square Garden or Wembley Arena. One of her backing musicians interviewed here describes watching her back and shoulders working like a prizefighter’s, such was the physical effort she put into her performances.

How could a global megastar once worth $250 million fall so far? Anyone who saw Whitney in her regal prime could hardly fail to marvel at her poise, her effortless command of the stage, and her voice, which could capture the finest musical nuances or let fly with a huge, concentrated tone capable of blowing the lid off Madison Square Garden or Wembley Arena. One of her backing musicians interviewed here describes watching her back and shoulders working like a prizefighter’s, such was the physical effort she put into her performances.

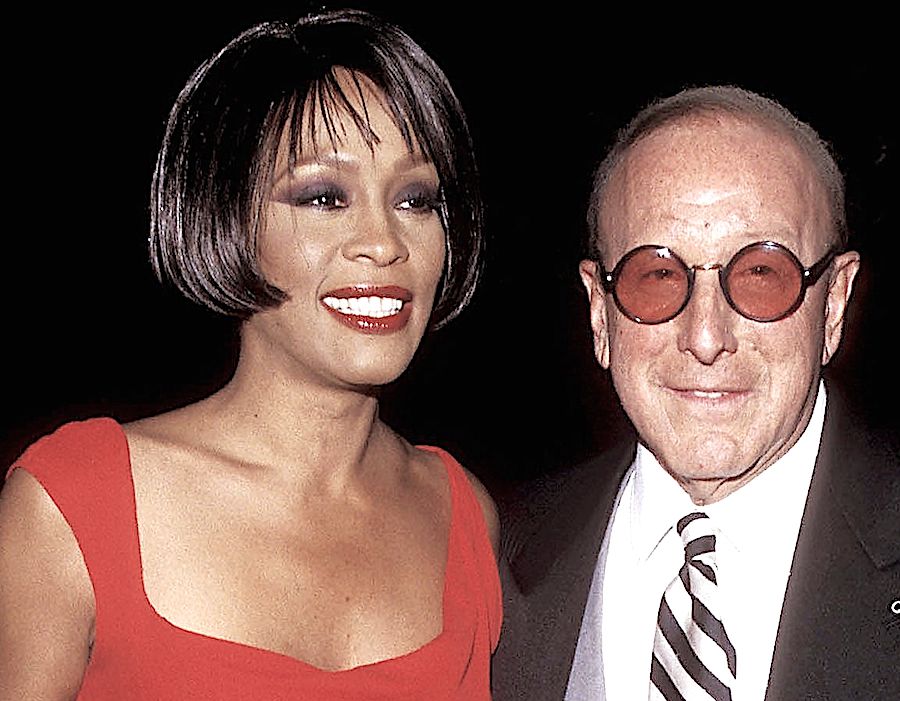

Crucial to the Whitney Houston story was Arista Records boss Clive Davis (pictured above with Houston), one of the last of the old-time svengalis who spotted Houston’s talent and spent a couple of years painstakingly working on songs, producers and the image he wanted his new protegée to project. Commercially, it worked miraculously well, but in turning a black singer into a pop diva designed to outdo the likes of Céline Dion or Barbra Streisand, Davis did a Henry Higgins number on her, extracting her from her background in gospel and R&B to place her on a gilded crossover pedestal. Broomfield duly highlights her fateful appearance at the 1989 Soul Train awards, when she was booed for being too pop and too “white”.

It left Houston badly shaken, but that was also the night she met Bobby Brown (pictured below). As one Arista executive puts it, “Bobby was street, Bobby was ‘hood.” The connection between pop’s perfectly-groomed golden girl and bad boy Bobby wasn’t as improbable as it seemed, since she’d grown up in fairly modest surroundings in New Jersey (the family moved from Newark to East Orange after race riots ravaged the former in 1967). Her brothers had introduced her to drugs, which were merely part of a normal night out. With Brown, it seems she felt she could be her authentic self with no airs or pretensions. He brought the booze, she brought the drugs, and soon they were both doing all of it.

Broomfield paints the broad picture effectively, and the film’s closing passages depicting Houston’s seemingly irreversible decline are difficult to watch. Burt Bacharach describes how she couldn’t sing in tune or remember which songs to sing at rehearsals for the 2000 Academy Awards, and her skeletal physique at a Michael Jackson tribute the following year is startling.

Broomfield paints the broad picture effectively, and the film’s closing passages depicting Houston’s seemingly irreversible decline are difficult to watch. Burt Bacharach describes how she couldn’t sing in tune or remember which songs to sing at rehearsals for the 2000 Academy Awards, and her skeletal physique at a Michael Jackson tribute the following year is startling.

Still, the film never quite gets to the heart of how such a giant of the entertainment industry managed to blow it so spectacularly. While Broomfield makes copious use of previously unseen footage from Houston’s 1999 tour, it offers incidental detail and colour more than genuine revelations.

Welshman and former royal protection officer David Roberts, who became Houston’s real-life bodyguard, is the most revelatory of the interviewees, but conspicuously absent are new interviews with Clive Davis, Bobby Brown and Whitney’s closest friend and confidante Robyn Crawford (said by some to be her lesbian lover). Nor has Whitney’s formidable mother Cissy Houston deigned to participate, though her old-school biblical morality and judgmental attitude evidently tested her daughter severely. A sequence where Brown and a tearful Houston discuss the fact that their daughter Bobbi Kris is putting on too much weight (possibly from the reality TV show Being Bobby Brown) is in distinctly dubious taste. A caption reminds us that Bobbi Kris, also an addict, died two years ago aged 22, adding a final dollop of misery to this thoroughly depressing tale.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

After the Hunt review – muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review – muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review – Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review – Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Add comment