Robin Ticciati on conducting Mozart - 'I wanted to create a revolution in the minds of the players' | reviews, news & interviews

Robin Ticciati on conducting Mozart - 'I wanted to create a revolution in the minds of the players'

Robin Ticciati on conducting Mozart - 'I wanted to create a revolution in the minds of the players'

Glyndebourne and Scottish Chamber Orchestra MD on three great symphonies

When Glyndebourne's Music Director Robin Ticciati conducts the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in the new production of Mozart's La clemenza di Tito starting tonight, you can be sure that it will sound utterly fresh, startling even.

This three-act orchestral drama, with the Fortieth Symphony as a hugely contrasting minor-key, semi-tragic centrepiece in marked contrast to the light-filled celebrations either side of it, marked Ticciati’s return to the concert platform after compulsory time out owing to an incapacitating slipped disc; this interview in Edinburgh the morning after an unforgettable Mozart trilogy was punctuated by his need to lie down or get up and move around. We’d last met at the beginning of what should have been a Brahms symphonies series with the SCO: I heard the First and was planning to return to Edinburgh for the Fourth, which inevitably didn’t happen because of the compulsory hiatus (nor did his planned appearances at last year’s Glyndebourne Festival). The good news is that he’s now back on course to complete the cycle in the recording studio, so his inspirational ideas on Brahms in conversation will not go to waste at the time of the set's release.

Talking to Ticciati on a specific project reminds me of the detail given, and the new light shed, on Mozart, Janáček, Beethoven and the Savoy operas in close succession by Charles Mackerras, his one-time mentor, in both cases I felt I was at a particularly thought-provoking tutorial. Mackerras’s Mozart example with the SCO, and indeed at Glyndebourne – he conducted Così fan tutte there a few weeks before his death – was bound to loom large. But Ticciati, a deep thinker, was always going to have his own ideas. We’d been talking before the microphone was switched on about Mackerras’s conception as SCO conductor, with similar experience of the period-instrument Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, to add one touch of difference with “authentic timpani”.

ROBIN TICCIATI Using gut strings I felt also was a way of getting them to want to... go deep is the wrong word...

DAVID NICE To colour differently?

Yes, colour differently and also look at the text of the score and have to re-analyse and say, what is the dagger, what is the dot, what is this slur, what does all this mean in relation to our bow now, and our string? So that's been one of my aims – I wanted to create a revolution in the mind of the players, and that's what's been so exciting this week.

And the beauty that they can still play with portamento [carrying the sound from one note to another]...

Exactly. I really wanted this classical portamenti with the finger gliding over the string, but I also really asked for colour at times, where we push the romantic door a little bit, especially in the Andante Cantabile of No. 41.

To hear gut strings with mutes on [as Mozart instructs in that movement] is such a radical difference, whereas with contemporary strings you put the mutes on and it doesn't sound so different.

Not as different, right. So colour and sound world have made huge differences. I think natural trumpets, horns, timps, now the gut strings, make more sense. I hope it's been a very important week for the SCO. Because that's how I see it and feel it.

Has Alec Frank-Gemmill [the SCO principal horn] played natural horn before – did he use it for Beethoven 5? [At the SCO 40th birthday concert in 2014: conductor and players pictured below by Colin Hattersley]?

Yes, the brass for the last 10 years have played on natural instruments. It can bring a surprising modernity. You mentioned those stopped notes – I said to the horns, when we have that corrosive, corrogated iron, acid sound, it needs to go right through you.

Yes, the brass for the last 10 years have played on natural instruments. It can bring a surprising modernity. You mentioned those stopped notes – I said to the horns, when we have that corrosive, corrogated iron, acid sound, it needs to go right through you.

Mackerras didn't use natural horns, did he?

No.

You see, I remember when he did those fantastic recordings of the later Mozart operas in Scotland, because this Royal Opera Così [conducted very slowly by Semyon Bychkov, which I’d just seen at the time] has been such a disaster in terms of dying on its feet, and I went back to the Mackerras Così...

So lively...

It seems to me that all his tempi were...

What it should be.

And yours are different, but they also convince.

I talked to the players about Mackerras's tempi in some of the breaks, and I said, tell me about how he approached his Mozart with you, and – I talk a lot about rhetoric and gesture and space and ideas and articulation, and then poetical sound worlds. He was very much about the tempo relationship which will then get that, and I find my route is from the other angle sometimes. It was fascinating to hear about that. You've got lots of experience of him, I know, and I have such huge respect, but it was lovely just with the orchestra to say... well, they could feel it, but they know from this week that it's been very special for me to take these symphonies and be with them in it with all their history, and for them to be 2000 per cent open, which is what one would expect, but it's still important that it happens.

Did they tell you what they felt were the differences or what he'd done?

Did they tell you what they felt were the differences or what he'd done?

Not for the most part. I did ask Adrian Bornet, the double-bass player who's been there a long time, to tell me a story from that time, but otherwise I actively didn’t want to go there too much.

What fascinated me was that not only was it wonderful that you did all the exposition repeats, but every repeat felt different. What happened?

I did Mozart 40 with the OAE in New York and Bob Levin was playing [the] K482 [Piano Concerto] in the first half, and he listened to the second half and he came up to me after the concert, he was very positive, but he said, What about the repeats? Because I certainly didn't do all the repeats then. And it was just enough for him with a big smile to say that for me to go – they're there for a reason, and we have to make that reason relevant today. Because the audience comes with such different perceptions and different types of knowledge, but I went on this – I believe in the repeats, but I also believe that when you go back, you are changed by what has happened. When you get to the end of the exposition and you finish on the dominant and the composer, instead of wrenching into a subdominant on the half bar, or diminished, decides to go back to the tonic again, the tonic is new. I talked a lot to the orchestra about ending bars, and the idea of repeats, and how we collectively decide, to use a Richard Jonesism, at what temperature we should go back, are we back again, or oh, we're back again, I didn't know this melody sounded like this the first time. I really got them into the mindset that we must be changed as an orchestra by going back, and that led of course, to freedom, phrase-lengths we can play with, dynamics we can play with, climaxes we can play with.

Things were sometimes a bit quieter, which can also be more energetically charged. To me the absolute point where I wanted to weep with joy was in the Minuet repeats – in 39, it suddenly just reached such a peak of delight, it was already wonderful. And in a completely different way the repeat of the finale of No. 40, you really want to hear that again. But the colours that emerge when that second theme comes back in the minor, the sfumato, you felt, yes, let's hear it again. The thing I've always felt with grander interpretations is that they can sound wonderful, but in the slow movements, even without repeats, do you want to hear that theme a second or a third time?

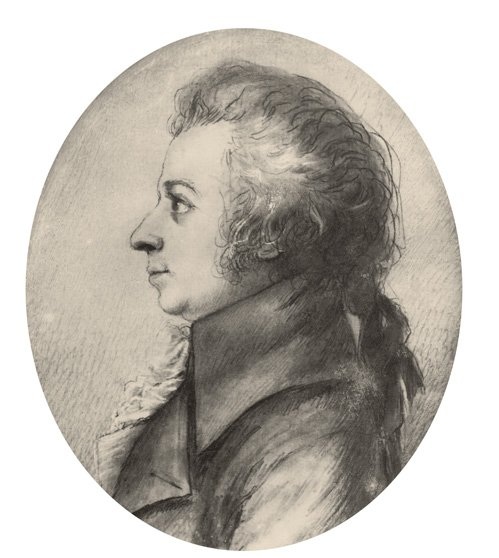

This is the thing – Andante... Norrington said something wonderful, I've never met him in person to hear him say it, but I've read it, and it's one of his great acidic remarks, there's a kernel of truth in it, that Mozart never wrote a slow movement. And this idea of what is an Andante, what Leopold [Mozart] calls the pace at which you find yourself walking. I think the exquisite beauty, the dissonance, the detail, must come through dance form and shape rather than this eking out of sentiment. It was very interesting in the 40 Andante, where I do the repeat of the development, it was interesting, a lot of the orchestra's eyes went up on the first rehearsal as if to say, are you sure? But I would think that all of them would miss it now, because that was another thing that we've all taken from this week, that it's not just about the structure of theme or the balance of a repeated section, it's about that in relation to the next symphony, in this case in relation to 41, and that affected a lot of tempi. For example the last movement of 39, Allegro, 2/4 [sings], I hope quite held and sunlightesque and in no way wanting it to be a zip-through, and then the Allegro molto of 40, cut time, a completely different world. We really worked hard on big tempo relationships. When you walked in here and said Wagner, that's exciting that in a sense you got the idea that the evening was a Gesamtkunstwerk [Wagner's term for 'total work of art']. (Pictured below: Mozart drawn by Doris Stock in 1789, the year after the composition of the three last symphonies.)

Totally. And it suddenly struck me for the first time that Mozart's 40th is his Tristan and 41 is his Meistersinger. And Wagner gets that idea of superimposing three ideas in the Prelude from Mozart's example in the finale of the Jupiter. It's analogous, it's not comparing the two directly. Isn't 40 within that framework so chromatic and radical?

Totally. And it suddenly struck me for the first time that Mozart's 40th is his Tristan and 41 is his Meistersinger. And Wagner gets that idea of superimposing three ideas in the Prelude from Mozart's example in the finale of the Jupiter. It's analogous, it's not comparing the two directly. Isn't 40 within that framework so chromatic and radical?

Exactly. And talking about chromaticism and the radical nature of it, we worked a lot on bow speed, because the bow felt new against the gut strings, how we would [sings the second subject of the first movement] find dissonance, we worked on that a lot, which is very interesting to wring out the agony but not let the boat sink, somehow. And it's lovely that you talk about Meistersinger and counterpoint, I was reading a lot; no that's a lie, I was reading a little though I'd like to read more, about the sublime and going back to Kant and Mozart was very interested in the sublime. And the sublime of mathematics. Mozart constantly refers to text and poetry with regard to his instrumental music, which I thought was very interesting. But it made me think that when we get to things in 40 and 41, the double fugue [sings the lines], he was intent with the orchestra on getting a clarity – not detachment but just incredible pointillist detail, and that helped to make us sure of all these superimposed shapes.

And with that ideal balance of wind and brass and strings, you could do that.

Exactly.

The detail was so startling, I was hearing things I hadn't encountered before. Often the wind are a bit smothered by the strings, but never here. Your talking about the tempo relations of the whole, I was thinking when you suddenly get those moments of pain in the Andante of 39, you're already thinking forward to 40, and when you hear the chromatics in the Menuetto allegretto of 41, you hear them more richly as a result of 40.

Exactly, so that the cross-fertilisation of chromaticism and motif is incredibly strong. And it's wonderful to find moments of resonance – there's this bit in the last movement of 40 where you get the strings [sings the grace-noted melody], and that looks forward to the same pattern in the first movement of the Jupiter, and another idea close to that in 40 looks back to 39, and in the space of five bars he's basically just used notes from two different symphonies and two different places, one of which he hasn't even written yet.

So yes, this idea that they're also linked in motif and chromaticism and ideas of pain, where the pain is in them, and the thing that strikes me so much, that we worked on a lot, is how Mozart can just change character in a second. And that was something that Colin [Metters, his first conduting teacher] used to tell me when I was 14 or 15, and I don't think I quite got it, I got the idea but I never really embodied it in my music-making of Mozart, and to get people to – he only writes piano for four bars and then forte, and so often you have a choice of whether the piano is something that leads into the forte, or whether it's something that ends and then the forte interrupts. Almost every moment, there's a decision to be made. And then out of that forte comes the light of a cadence that's OK. An example of that is the end of [the Andante of] 39 [sings], that last chromatic dissonance before the return to the main idea [sings] and at the beginning we were ending (dotted rhythms), intact in time, I said after this dissonance trust the tempo 1, that it just goes out the window. Find contrast. So we really looked for contrast. And risked maybe – I am aware also that I need to find the balance, how much contrast Mozart wanted, what type of explosive range, he goes on about always having beauty in his music, and I know at times I want a destructive sound and something that actually nearly breaks the mould. It's also because I feel that we, as listeners today – the music can take that, the halls, what we experience as humans, different types of music. (Pictured below: Ticciati conducting, by Marco Borggreve)

And all the music that we know that was composed after – it struck me last night that 41 looks so much more forward to Beethoven 7, the tremolos and the energy. And you're doing that at the end of the season, aren't you?

And all the music that we know that was composed after – it struck me last night that 41 looks so much more forward to Beethoven 7, the tremolos and the energy. And you're doing that at the end of the season, aren't you?

Exactly, that will be my first Beethoven 7. I hadn't thought of it but it's nice to think of that.

Also having drums and trumpets in 39 and 41 and not 40 – I had never twigged that 40 doesn't have timps.

Because you would somehow expect that. One thing that really struck me doing it with the orchestra this week is that Mozart 40 is so full and yet so unexpressionistic. It's got a spareness about it. And the difficult thing about that symphony is to give it all that it needs but at the same time just speak on its own. The balance of 40 between 39 and 41 is extremely hard to navigate. We've worked hard on that.

Having an interval helps. Like you need a long interval between second and third acts of Wagner. And it can be transformed either from light to dark or dark to light.

The light of 41, the last movement feels like such a crown in relation to 39 and 40, of course when you do it on its own 41 is another thing and also incredible, but there's a real sense of peak.

Like the Liebestod in context, not detached in concert. You must be happy with the new players.

We're working so hard. They're always trialling with me and I put in my tuppenceworth, and every orchestra is different, and this is player-decided, player-run, but of course they all come to me and say, What do you think? We have a good relationship like that. The SCO take their time, sometimes to the extent that you think, are we going to make the decision, but they're careful because they want to get the right person. They have a great track record. You know, Philip [Higham] on cello, Marcus [Barcham Stevens] on principal second, and of course with the gut strings a lot of the players have a history of playing in the Dunedin Consort or the OAE, so a lot of them came back and said, It felt like coming home in this repertoire. That was a great thing to hear.

But giving it a bit more of a romantic feel – Norrington never allowed portamento.

Well, I don't know about portamento, he never allowed vibrato. But I just feel that... I presume from Roger's ideas that it's now a matter of taste with him, he just doesn't like vibrato, it's got to that point. But I feel that reading Leopold, the idea of an ornament in vibrato and the way he talks about singers, it's vibrato as ornament, as colour, as the one romantic leaf that can make us think about where he's taking the symphony, the music and the form. Like everything, and this is the thing that has made me feel free about this approach, more and more it comes down to taste. We can read, we can study, have opinions, but ultimately it's the conviction of how the interpreter feels that the music is best delivered, or how the composer can be released in today's world, and presumably there's just one moment where rule, dogma, source material just has to vanish and – bam. You are then in charge of making this live.

In charge and also free [Ticciati pictured right by Giorgia Bertazzi].

In charge and also free [Ticciati pictured right by Giorgia Bertazzi].

i just think the essential thing is to have done the preparation in order to then be free.

You had a long period off – has that made a difference, in terms of study?

I couldn't look at music for two or three months. In no way to be overdramatic about it, but just one sentence on it: nothing like that has ever happened to me before, and I did think, Is my body the type of body that can do the kind of job that I do? And when you have those thoughts, you have to disappear from music for a bit. There's a lot of time for thinking.

Is the maxim, learning through suffering, any use, or would you rather not have gone through that?

It's quite an extreme way of learning [laughs], but everyone has their own route through this life. If it's given me anything, it's certainly this idea of thankfulness – look at what we do have, breath, light in the morning, it's given me a lot of things.

There did seem like an exceptional joy last night – did you get that sense?

I think what's wonderful is that there is this moment where the work has to be done, since the job – I call it a job not because I see it that way but because it's the best way to describe it. For the audience, the job must be done, and the emotion of experience and suffering and relationships has to be left at the door. And I think what is beautiful is that the orchestra knows what I've been through, I know what I've been through, it's not talked about, maybe apart from one little comment in the corridor to someone, but knowing them now for as long as I do, they know what's going on, and I know they're there.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment