theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Robin Ticciati | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Robin Ticciati

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Robin Ticciati

Major new force in British music discusses adventures at Glyndebourne and in Scotland

Poised when I met him six weeks ago between 40th anniversary celebrations of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, of which he has been a shaping chief conductor for the past five years and putting his new music directorship of Glyndebourne into action, Robin Ticciati hardly seemed like a man in positions of power, more an idealistic youth with a touch of the dreamer softening a powerful intellect.

He was much the same, in short, as when I’d first encountered him sharing a 2009 Glyndebourne study day on Janáček's Jenůfa (Ticciati holding the score below) in the then-26 year old’s last year as music director of the house's Touring Opera. There were friendly hugs all round – even I got one at the end – and impassioned work from the piano with the very talented covers of the leading roles, Miranda Keys, Svetlana Sozdateleva and Christopher Lemmings.

They praised his clear directions to the stage from the pit, not a given among opera conductors, and much was said about the value of intense silences, subsequently borne out in electrifying performances. We talked about the power of the silences again before I turned the recorder on, sitting in a noisy Holborn Pret a Manger not long before Ticciati was due to began work with the brilliant Richard Jones on Der Rosenkavalier, Glyndebourne’s first production of the season opening next week, down at the country opera house.

They praised his clear directions to the stage from the pit, not a given among opera conductors, and much was said about the value of intense silences, subsequently borne out in electrifying performances. We talked about the power of the silences again before I turned the recorder on, sitting in a noisy Holborn Pret a Manger not long before Ticciati was due to began work with the brilliant Richard Jones on Der Rosenkavalier, Glyndebourne’s first production of the season opening next week, down at the country opera house.

DAVID NICE You’ve now had quite some experience with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, superbly documented so far in your revelatory Berlioz recordings together, and now you’re building on what you achieved with Glyndebourne's tour company by taking over the helm of the main season. How do the two principal conductorships connect and in what ways are they different?

ROBIN TICCIATI My immediate reaction is that they’re completely different, that I’m dealing on the one hand with symphonic and chamber music and on the other with singers and directors. In one sense the worlds seem completely apart. And then if I think for a little longer I immediately feel that tidal-wave of cross fertililsation.

Because you conducted a concert performance of Don Giovanni with the SCO at an early stage (below, Ticciati in Scotland photographed by Marco Borggreve).

Yes. But I think basically the activities are very different. Though what opera brings to symphonic work and what symphonic work brings to opera is an amazing mix, and I think the similarity is the intense level of musical detail and preparation that I love to work on with the groups of musicians I get [in terms of the players at Glyndebourne, the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Richard Strauss and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment for Mozart]. With the SCO it’s not exactly a laboratory, but it does turn into one as well. It’s the idea of this incredible group of musicians where we can discover and look at a score in a detailed way, and see what comes out, and at Glyndebourne it’s the same in the rehearsal period.

You like to be there at the beginning, at the first piano rehearsal.

I feel I have to be…

It’s so rare, Vladimir [Jurowski, Glyndebourne’s previous music director] did it and you do.

It’s so rare, Vladimir [Jurowski, Glyndebourne’s previous music director] did it and you do.

It’s the only way – well, it’s not the only way, of course. Magic can happen when there’s only one rehearsal, if you’re at the Vienna State Opera - I haven’t been there, but that type of European theatre where you haven’t met the singers, there can be a special kind of energy, and the flipside is that having lots of rehearsal doesn’t guarantee great results. But it gives one the possibility to get to a place which I think is so special and relates to my kind of personality, which is building something and making music with people, and in order to be with people you have to understand, breathe with them, look, look again. And that kind of relationship with a director – at times I’ve spent four weeks there with a new production, and with Richard Jones, it’s a team, and talking about those things, about the quality of silence we were discussing – it’s in the rehearsal period that you fine tune that amount where you can take a little more here, very little there, and if you want something, you fight against each other and come to a common idea, and you need that.

And does your discussion inform the way you conduct?

So much – the wonderful thing about that, to start with Richard, we’ve been talking about Rosenkavalier for a year, a year and a half. He’s somehow understanding of the music and the text, and then the interpretation that he comes to, for me it’s a gift for opera and it’s a gift for working together. We’ve been talking a lot because you need to talk about the piece to know about what direction we want to take, and everything that we want to achieve, not that you set out thinking about what you’re going to achieve, but it’s really important that we met to sow our seeds for the vision of what the piece is. That’s informed his learning of it and my learning, I’ve already started some gentle work, the process hasn’t begun yet.

Was there a specific key that unlocked Der Rosenkavalier for both of you?

From my point of view the size of Glyndebourne, the chamber music aspect and the size of the voices that we’re using fed into his idea of analyzing the gold gilt that the piece is surrounded with, the sentimentality, the nostalgia, and really what we are meant to feel, what we could be feeling with it, and the big danger I think is that the audience is sitting there and is in tears, but enjoying it all and feeling very good at the same time. And I think to get into the real play of the piece is where Richard is so remarkable – this is a play, with the most incredible Viennese tone poem and Mozart going on underneath, and to find the reality, to find who the Marschallin really is. Strauss and Hofmannsthal suggested a young woman, 32, and that already throws into relief the preconceptions people have about who this grande dame really is, and the 11 o'clock number of the Trio and the end of Act One. So it was all these conversations which have just begun with drip-feeding, then we have five weeks to put it together.

What’s Richard's basic conception for it?

The setting is a mix between the time when it was written [1909-11] and the time that it’s representing [c.1750], I think I can say that.

He’s very good at that sort of double consciousness…

And the mélange of that and how the acts develop and suture into something that’s probably a culmination of it all and also outside it all as well. The idea of what we are meant to be feeling at each point, that’s what we’re really working at. And – look, it seems a bit butterfly, this, but I sit here and think about Baron Ochs and how to really excavate who that character is and how you engage with him and how he engages with the audience in a way that grips us, and that we are really interested in him. That’s something that takes a lot of physical work.

The McVicar production when I saw it in Scotland was the first time I saw a really strong feminist side in the Marschallin, how angry she is at the men's automatic sense of privilege – how Sophie is really her at a much younger age. That also reminds me that Glasgow's Citizens Theatre performed it at the Edinburgh Festival as a straight play.

It is a play, I think. We have two, three days of straightforward music rehearsals, just to get an overarching shape of the piece and see where everyone is. Then it’s four weeks of intense rehearsal, I’m there through it all.

And you work with a reduced orchestra? Not quite a chamber orchestra but smaller than Strauss would have used?

No, look, it’s 14.12 [in the number of violins]

Last time Glyndebourne needed Boosey & Hawkes's permission to use a smaller-scale performing version – but was that because it was in the old house?

Exactly. No, we’ll have the full orchestra, and when Strauss specifies just half the sections, we do the same. Looking back at their history through the years, I’ve seen how the different scales were handled. And what Vladimir did with Ariadne auf Naxos last season…I was just bowled over.

Did you like that production [by Katharina Thoma, someone else who speaks highly of Richard Jones]? I did.

So did I, I really did. I think what I loved about it was that an interpretation where we heard the music in a different and exciting way. Perhaps for me the apotheosis [of Ariadne’s duet with Bacchus] at the end didn’t quite lift off. But how wonderful that there was this idea to connect the two halves of the piece.

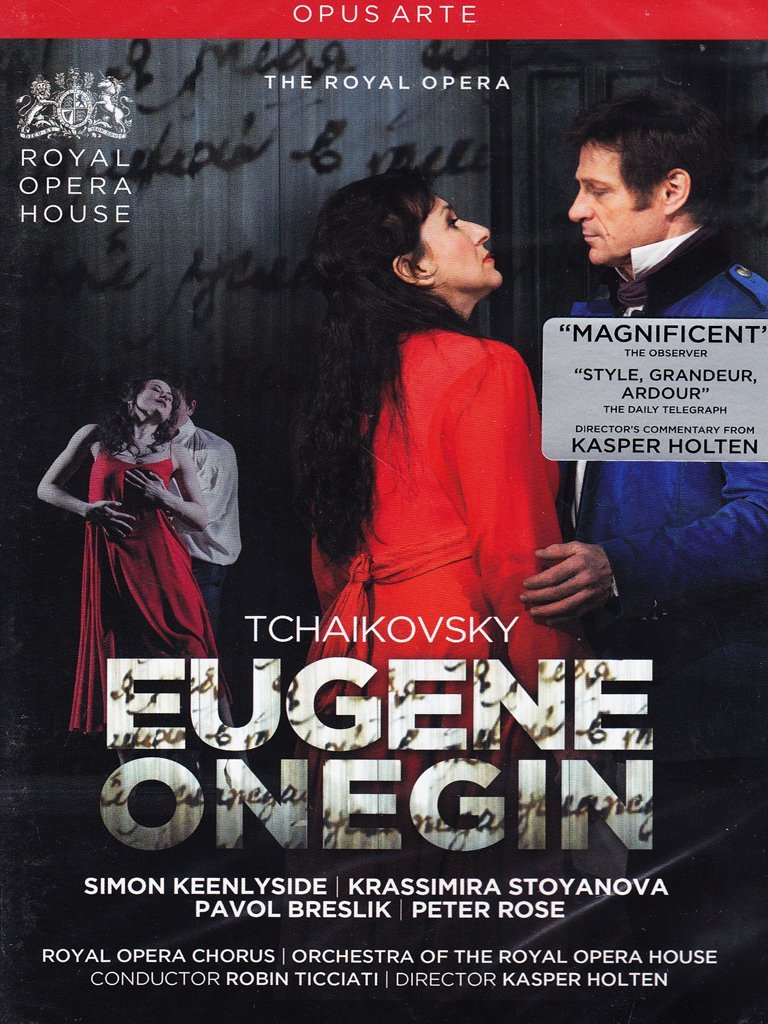

I was anticipating the end would be rather sober [set as it was in a kind of Glyndebourne country-house requisitioned as a wartime hospital], so I suppose I was impressed by the fluttering drapes and the fact that there was a sort of transcendence. Interestingly that links with another production which people seem to have a lot of problems with, and I seem to be one of two or three that really admired Kasper Holten’s Eugene Onegin at Covent Garden, which you conducted and which I found very thoughtful, very moving, and having watched the DVD (pictured right) I found it even more extraordinary. Did you have difficulty establishing what you wanted, did it take time?

I was anticipating the end would be rather sober [set as it was in a kind of Glyndebourne country-house requisitioned as a wartime hospital], so I suppose I was impressed by the fluttering drapes and the fact that there was a sort of transcendence. Interestingly that links with another production which people seem to have a lot of problems with, and I seem to be one of two or three that really admired Kasper Holten’s Eugene Onegin at Covent Garden, which you conducted and which I found very thoughtful, very moving, and having watched the DVD (pictured right) I found it even more extraordinary. Did you have difficulty establishing what you wanted, did it take time?

It’s hard to say, because you look back and think what was it like, because when you’re in it you’re analyzing but you’re going towards this vision. Kasper’s idea of the doubles [a younger and older Tatyana and Onegin], with our cast Krassimira [Stoyanova] and Simon [Keenlyside], the idea of looking back with melancholy, I thought that was so beautiful, and I thought it gave the music a lot of different possibilities.

They’re both very truthful singers, but perhaps they could not have been convincing as the young people.

I wouldn’t like to say that, but I loved what they did, and there’s something regal, noble, stoic about Krassimira, and I thought this was such a lovely picture, it opened doors which I wanted to go down. From my point of view I was very keen that it would be this tableau-like, smaller-scale Onegin where Act One really had this Apollonian classicism, even ushering in the harps coming in, corresponding to Tchaikovsky’s idea of staging it with Moscow Conservatoire students, and the later acts could be more romantic. Maybe there I didn’t quite realize that as much as I could have done in sound and structure to make it tell, if I look back on it, but in terms of the process, we had such a wonderful time and the theatre works amazingly well and I thought Kasper was wonderful to work with and the singers were right there, I’m really pleased you liked it, I’m so aware it wasn’t for everyone.

I don’t understand what people found so difficult, the idea is easy to grasp and as Kasper himself said it wasn’t exactly regietheater at its most extreme. I thought the idea of the older person holding the younger was incredibly moving, and I’ve never heard the heart of Tatyana’s Letter Scene, the oboe solo, more beautifully done, because you paced the earlier stages so lightly. It can feel, where’s the action, but you weren’t any one thing, you gave the big moments space and elsewhere moved it on. As for rubato and freedom, a conductor either has it or not – is that something that comes naturally to you?

I think it’s somehow to do with my love and quest for understanding tonal structure and classicism, the idea of tonic and dominant, and that polarity and how a piece, if we’re in a tonal setting, gets from A to A through many different things. Hopefully I work on this, but it’s given me a sense of how you can have a line which leads through very clearly where you are, and at the same time if you can take time on page three of a score and know that on page 30 it will affect that, that’s how I deal with it, and I think it’s the tonality that leads me through it, and hopefully not whim or extravagance or because I want to do it now. Maybe those things I can also begin to develop, the idea of going emotionally outside the box to find what’s there, if I risk breaking down the series of what I see as structures even more, and that’s my starting point and gives me a feeling of what rubato is necessary, or the piece can take. Does that make sense?

Absolutely. So when you don’t have tonal boundaries, and you conduct quite a lot of contemporary music with the SCO, what do you do then?

I suppose then I’m guided much more by primary colouristic, rhythmic effects, a modal structure if it’s there. The piece then works from a different angle, possibly it’s text led, so when you learn a piece – I always try not to listen to a recording, and maybe there isn’t one for a new piece, I think ultimately it’s what you feel and what you want to say with a piece, that’s the only thing eventually you have to go on. I don’t want to overplay the intellect or the heart, because there’s that beautiful balance where the intellect and the heart talk to each other.

Does that mean that you have a preference for a certain repertoire, and that you feel less keen, for example, to work on new commissions because you can’t guarantee the end product?

No, I feel very much open to a lot of repertoire. Maybe pre-Mozart or early classicism is not an area I want to go in to conducting-wise at the moment, and perhaps the whole Russian Socialist-Realist area, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Myaskovsky, that’s not something which my heartbeat somehow relates to, and that’s something that I’m not so comfortable with. I know objectively even hearing Shostakovich, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the symphonies, the concertos, that it’s remarkable music from a remarkable source and the whole history of personality that’s led to these compositions. It's just the idea of what type of food you like and don’t like, you can still look at a chef and say, that is the most remarkable preparation you've made there, but I don’t want to eat it. For me the fields are classical, romantic, French music especially, through to contemporary. The thing with contemporary music is that if it’s a premiere, there’s a freedom which is unbelievable, there’s no preconceptions, and there’s also this feel that you are creating… We have this composer in residence at the SCO –

No, I feel very much open to a lot of repertoire. Maybe pre-Mozart or early classicism is not an area I want to go in to conducting-wise at the moment, and perhaps the whole Russian Socialist-Realist area, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Myaskovsky, that’s not something which my heartbeat somehow relates to, and that’s something that I’m not so comfortable with. I know objectively even hearing Shostakovich, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the symphonies, the concertos, that it’s remarkable music from a remarkable source and the whole history of personality that’s led to these compositions. It's just the idea of what type of food you like and don’t like, you can still look at a chef and say, that is the most remarkable preparation you've made there, but I don’t want to eat it. For me the fields are classical, romantic, French music especially, through to contemporary. The thing with contemporary music is that if it’s a premiere, there’s a freedom which is unbelievable, there’s no preconceptions, and there’s also this feel that you are creating… We have this composer in residence at the SCO –

Yes, I was there at the 40th birthday concert (Ticciati at the concert above with Maria João Pires, photo by Colin Hattersley) – you premiered the new work by Martin Suckling.

Yes, to have that connection, to be able to be in dialogue with a composer –

He comes to rehearsals –

He does, and I say I don’t know what you mean by that, and he’s saying maybe we should change this here, this is the essential dialogue of music-making…

It’s a bit like working with Richard Jones, but from a different perspective.

Exactly, and for me those things are very, very important. Anyway, I just feel it’s so important not to feel as a musician you don’t have to conquer every kind of facet, then it’s this wonderful balance of risking what to conduct or not, finding the journey, I go with my gut a lot of the time with what feels right or is going to feel right.

So Mozart’s a constant, and has been since you started conducting the SCO.

Actually my first season with them was Berlioz and Haydn. Then Mozart, and symphonically speaking I’ve had quite a time away from Mozart on the concert platform, following instead the whole progression into Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, that’s been something that has absolutely fascinated me. In the opera house, Mozart has been a constant [Mozart’s first opera with passages of real maturity, La finta giardiniera, is Ticciati's second Glyndebourne opera this season]. It’s not to say that I don’t think the symphonies aren’t remarkable, but when you get in with text and drama, this relationship with humanity and people, in the theatre, that’s staggering, and I’ve learnt a lot from him and through him about music-making. But actually I continue to have a bit of time away, with the SCO maybe in 2017, 18 I can start planning more symphonies, another opera. But next season it’s Haydn and Mahler.

The First Symphony?

No, Mahler Four. Well, look, the idea of more Mahler came about when we did Das Lied von der Erde in a chamber version a year and a half ago. I’ll tell you what it was, when you see a group of players in a repertoire that you’ve never explored together, I suddenly saw my principals in a different way, I saw Maximiliano [Martín], say, our principal clarinettist, as a different animal, and I saw myself and my preparation and love for the music take off, and I thought, ah, there’s something here if I can relate and find the pieces that I think we can bring something different to on more of a chamber level, then this pairing with Haydn will be really special. The idea of Karen Cargill (pictured above) singing the Kindertotenlieder in the Queen’s Hall with those sinewy woodwind lines and a small number of strings, sitting alongside Haydn and a contemporary piece, I hope it’s going to be something different for all of us. I wrote a little introduction for the programme, I said you’ll think, Mahler with a chamber orchestra, why on earth, and Haydn as a main course, because everyone says Haydn doesn’t sell, but I just feel he can be such a musical enlightenment and challenge.

No, Mahler Four. Well, look, the idea of more Mahler came about when we did Das Lied von der Erde in a chamber version a year and a half ago. I’ll tell you what it was, when you see a group of players in a repertoire that you’ve never explored together, I suddenly saw my principals in a different way, I saw Maximiliano [Martín], say, our principal clarinettist, as a different animal, and I saw myself and my preparation and love for the music take off, and I thought, ah, there’s something here if I can relate and find the pieces that I think we can bring something different to on more of a chamber level, then this pairing with Haydn will be really special. The idea of Karen Cargill (pictured above) singing the Kindertotenlieder in the Queen’s Hall with those sinewy woodwind lines and a small number of strings, sitting alongside Haydn and a contemporary piece, I hope it’s going to be something different for all of us. I wrote a little introduction for the programme, I said you’ll think, Mahler with a chamber orchestra, why on earth, and Haydn as a main course, because everyone says Haydn doesn’t sell, but I just feel he can be such a musical enlightenment and challenge.

And in so many of his symphonies there’s something extraordinary which stands out.

And of the theatre as well, and his relationship with Mozart and Beethoven, and sometimes people forget, he’s there, as the father of a lot of things.

As a precursor to Berlioz he’s interesting, too. When you hear Beecham conducting Haydn, those colours and the force of personality come out. They’re still valid, even though we’ve had the authentic movement since then.

It’s interesting, this idea of validity, isn’t it, I’m almost terrified by the word, I think it might be too strong, but there are some times when I think – we now know too much to know that that just isn’t right, and maybe that’s where the word comes in. Because we built this relationship over time where there’s this element of play, and reversing to the extent we can then let the piece live in a classical salon way, as a premiere kind of feel. I hope we can bring a lot of things to Haydn which people will really be excited by.

Because it was with the SCO that [Sir Charles] Mackerras did this wonderful thing of bringing authentic ideas to a contemporary orchestra, with such a fine ear and judgment.

It’s remarkable. And what actually felt so wonderful over these years it feels that we’re extending and progressing and taking further into different places but still with his spirit, what he brought.

You had some lessons with him, didn’t you?

On Jenůfa, yes.

I felt he was like a university lecturer in an inspiring one-to-one whenever I went to talk to him. People said he had been very difficult in the 1950s and 60s, he must have mellowed.

I think it comes back to the music. It was all at the service of the music.

I remember him talking about the opening horn call in Schubert Nine, if it was written for a valveless horn the weak notes couldn’t be sustained at a slow tempo. But maybe if you’re a great personality and you think it should go that way, if you’re a Furtwängler, you can convince.

Exactly. Vive la difference, it’s all there, But even with taking that idea of the valve horn, you then get recitative [sings the Schubert opening], it’s almost like looking back to something pre-baroque, a hymnal type chant, it could have text, articulation, breath, then you go even further.

Is there a difference between Mozart and Beethoven, in that Mozart always sings and can seem to be related to some imaginary text, with Beethoven less? I’m thinking of that Fifth you conducted with the fantastic horns.

Is there a difference between Mozart and Beethoven, in that Mozart always sings and can seem to be related to some imaginary text, with Beethoven less? I’m thinking of that Fifth you conducted with the fantastic horns.

It’s a very good point – and I’m so pleased you liked it, because the thing I thought so much about, and maybe why I’m giving Mozart a rest in concert, is to explore the idea of these granite like, these marble like sculptures and blocks within this classical-romantic music of Beethoven, and to more fully understand the idea of the harmonic revolution that he had. With Beethoven Five I don’t think so much of melody – even this dolce theme of the slow movement, I thought it was a set of shapes that culminate in something which maybe we do feel as melody, but not immediately to think of it as "instrumental" and "vocal", and I talked to the orchestra a lot about that. I didn’t use a baton for the piece, I don’t know if it makes any more difference, but I felt that when I stood in front of them with a baton, I got a sound and a feeling from them that was about line and - well, plushness is going too far, but something that was already dangerously singing or sentimental or romantic, and I said, I want to treat it as clay, as something that’s slightly more abstract. Which is a long way of saying I agree with you, about this idea of Mozart and Beethoven, and that was really remarkable to grapple with. We’ve just taken it on tour to Japan and Korea, and we played it about six or seven times.

Did it vary according to the halls that you were in?

Totally, also it varied according to mood…you get to that last movement and the sense of joy, freedom, the question of what kind of C major it is, it all depends on the journey of the previous three movements, and because of the different heartbeats people have, or how the day was, how the rehearsal went, it always meant that the idea of release into C major was something aesthetically different each time, and also to let them know it would be different, we really explored that.

I must say I thought before I heard it, this is an odd programme for a 40th anniversary celebration.

Oh why, tell me?

Partly because in the Chopin [Second Piano Concerto, with Pires] there wasn’t much orchestral interest, though you made it so…

You didn’t hear orchestral interest?

Well, I heard more than I expected, especially from the bassoon. But I thought, if it’s Pires then why not Mozart or Schumann, concertos which might celebrate the orchestra more…

Look, I’ll tell you exactly where that came from, it was the idea of how I’ve inherited the orchestra and what I hope I can develop and bring to it – the three facets, contemporary, classicism and romanticism, that’s what I feel I could live with. So it was the idea of having our new wonderful young Scottish composer, Chopin from the kind of Berlioz/Mendelssohnesque period where it’s salon romantic - and it was interesting to see where it went on the tour, I love her playing of the piece - and then the warhorse Beethoven Five. That was the idea behind it.

Your Berlioz with the SCO has been extraordinary. A friend of mine waxed so lyrical about Karen Cargill in Les nuits d’été, said it was one of the best he'd ever heard, so I got it and he was right, and as for La mort de Cleopâtre... Where does the temperament come from? She’s an ordinary Glasgow girl…

Your Berlioz with the SCO has been extraordinary. A friend of mine waxed so lyrical about Karen Cargill in Les nuits d’été, said it was one of the best he'd ever heard, so I got it and he was right, and as for La mort de Cleopâtre... Where does the temperament come from? She’s an ordinary Glasgow girl…

Yes, where does it come from? She gets up there and she’s gripped by it. And look, isn’t it one of those wonderful things, she is an ordinary, beautiful, honest Glasgow girl, and maybe it’s the idea of the music when she’s in front of it and in that moment releases something that ordinary life cannot grasp or get hold of, isn’t that the way with some people sometimes? She is a very special singer, and she was there at my very first concert with the SCO, we did the Death of Cleopatra in 2009. And so we got onto this Berlioz journey, I’m so thrilled. And of course the big thing for her is Dido [in Les Troyens], and that will be a great moment.

Are you planning it?

Well, let’s just say it’s in our minds a lot and it’s just a question of when, it seems the most natural progression of everything we’ve gone through. Of course we will do Roméo et Juliette because it's the missing link after the Symphonie Fantastique…it’s got everything.

For the Fantastique you had a very special sound. Were you thinking of how it might have sounded then?

Not so much, because you see the score, it’s au moins de vingt, 20 first violins, he wanted a massive orchestra, there’s no doubt about it. That came three years into working with the orchestra, it was after having done L’enfance [du Christ] and Les nuits and La mort, and I thought, OK, we can do certain things with it, when I had a sound in my mind, that’s the basis, and a feeling of what I had to say, I knew that the players could deliver what I wanted. So it isn’t a question of validity, I’m quite happy for people to say, it’s not big enough, you lose some things, I was just very pleased with the things that we gained…

…The clarity of the woodwind, not having to battle against too many strings.

Exactly. And all these minutiae of marking, it was the idea of bow strokes, the idea of Beethovenian dashes and daggers, and how that then goes into the early 19th century, and what he might have been doing with these markings, are the cellos and basses at the tip, on the point, rather than off the string, modern shiny staccato, something that’s very professional but not necessarily what the music is about. And I think you have to have a relationship with a symphony orchestra – as with an opera company - over a long time to make sure you get those kind of results.

- Robin Ticciati conducts Der Rosenkavalier and La finta giardiniera in Glyndebourne's 2014 season

- Full details of the SCO's 2014-15 season on the orchestra's website

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

This is a wonderful