Agnès Poirier: Left Bank review - Paris in war and peace | reviews, news & interviews

Agnès Poirier: Left Bank review - Paris in war and peace

Agnès Poirier: Left Bank review - Paris in war and peace

From bleakness to exuberance, a flavoursome history of the French capital in the 1940s

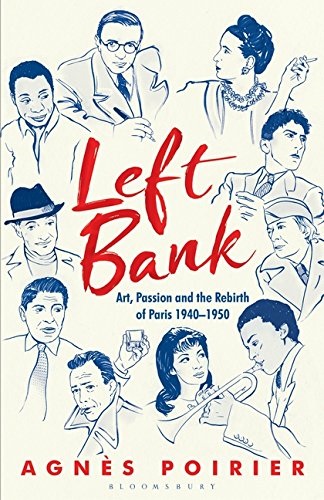

In Left Bank: Art, Passion and the Rebirth of Paris 1940-1950 Agnès Poirier has chosen an unusual decade on which to concentrate. This is a truly original take on whatever makes Paris Paris. Here is the City of Light at a time when the lights were dimmed, and not everybody thought they would turn back on to brilliantly illuminate this humiliated cultural capital. The Occupation was still for many a source of shame, the history of the collaborators obviously more shrouded and shadowed than that of the Resistance, and its immediate aftermath has not been much studied, in English at least.

Those who lived in the city in 1940-44 were those who for one reason or another could not leave. We are told of the mental and physical strain of the times, the guilt and distress, and of acts of secret defiance: Picasso somehow managed to survive – perhaps a story not yet fully told – and even commissioned the Hungarian photographer Brassai, who was also in danger, to photograph his work. The teenage Juliette Gréco was imprisoned and managed to survive when released by hiding in the flat of the actress Hélène Duc (her mother and sister had been sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp).

Those who lived in the city in 1940-44 were those who for one reason or another could not leave. We are told of the mental and physical strain of the times, the guilt and distress, and of acts of secret defiance: Picasso somehow managed to survive – perhaps a story not yet fully told – and even commissioned the Hungarian photographer Brassai, who was also in danger, to photograph his work. The teenage Juliette Gréco was imprisoned and managed to survive when released by hiding in the flat of the actress Hélène Duc (her mother and sister had been sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp).

Then came the euphoria of the liberation and its aftermath: everything changed as new visitors poured in to stay, for varying lengths of time. For Americans, the GI Bill brought many back, post-war, to revel in past glories, as well as in that quintessentially American pursuit of finding themselves. Black Americans came too, from Richard Wright and his family to James Baldwin, to flourish in a cultural atmosphere that was strong on tolerance, and the euphoric energy released by war’s end. The staggeringly gifted black trumpeter Miles Davies came, aged 22 and on his first trip to Europe, to the first Paris International Jazz Festival, and had a passionate involvement with Gréco: the singer and actress did not understand until they met in America several years later that their pairing would have been impossible in the US.

The decade of course has its usual suspects – Picasso perhaps chief among them – but such a huge cast of characters appear in this formative period; the key phrase the author chooses to describe its ethos is that they found war their master, Paris “their school of life”. We are given an almost day-by-day narrative of the years of the Occupation: the attempts to survive through it would prove paramount in the explosion of ideas and emotions that came with the end of war, as Paris reclaimed her intellectual eminence.

From just before Poirier’s decade there is a vivid description of the amazing evacuation of the contents of the Louvre, orchestrated by its extraordinarily prescient director Jacques Jaujard (himself only in his early forties) in 1939, beginning the day after the Nazi-Soviet pact was signed by Molotov and von Ribbentrop. With extraordinary efficiency, fuelled by adrenalin, 4,000 masterpieces, including the Mona Lisa, in 1,862 crates coded according to contents, were loaded over three days into 203 vehicles, leaving Paris for castles and isolated chateaux accompanied by their curatorial carers and guardians to repose in safe seclusion until the end. Poirier ruefully observes that it was a far more successful operation than any the French Army could manage. In less than a year, Hitler was photographed posing in front of the Eiffel Tower.

Existentialism replaced Surrealism, and the political debates were endless in those heady moments of optimism before the Cold War’s icy clouds cast their shadows

The Fall of France, the fear, and the attempts, some successful, to leave are all vividly described. Henri Cartier-Bresson, for example, was a prisoner of war for nearly three years before he escaped. Arthur Koestler was sheltered by Sylvia Beach; he managed to get the manuscript of his mesmerising novel Darkness at Noon out of the occupied city. It’s a broad canvas, from the famous names like Jean Cocteau and Simone de Beauvoir, to post-war visiting North Americans from Norman Mailer, Irwin Shaw and Saul Bellow to Ellsworth Kelly, only 25 when his sojourn in Paris changed his art and life. Alongside those who can be thought of as “Euro-Americans”, such as Alexander Calder, or those primarily now identified with Paris (Samuel Beckett), plenty of less familiar names feature too, in changing international patterns.

Existentialism replaced Surrealism, and the political debates were endless in those heady moments of optimism before the Cold War’s icy clouds cast their shadows. Just a few months after the Occupation ended the magazines burst into life: Jean-Paul Sartre founded Les Temps modernes. Intellectual debates were everywhere, not to mention complicated amorous entanglements (de Beauvoir’s post-war encounters with the younger American writer Nelson Algren were surely one of the most fascinating). Poirier’s subtitles for her detailed accounts of all such kinds of encounters sum up in shorthand her complex stories of real people: husbands, lovers and friends create changing patterns in post-war Paris in the chapter “Love, Style, Drugs and Loneliness”.

French fashion roared back into life, with Christian Dior a prominent figure and the models themselves headed into the high life. For the writers, pills and drink became a way of life, but the work they produced was prodigious. Everybody knew everybody, clique following clique, rivals as well as friends: the density of acquaintance produced endless permutations in what we would now call the creative industries. This New Dawn encompasses the birth of New Wave cinema, and Poirier concludes with a convincing description of the teenage upper-middle-class Brigitte Bardot training as a dancer in Paris in 1949, epitomising a child of Existentialism with a new freedom from social constraints, doing what she pleased.

Some 30 pages of notes hardly do justice to this extraordinarily fact-filled narrative – the author clearly delved deeply into archives, as well as interviewing all those she could, including the octogenarian Juliette Gréco. Poirier makes a convincing case for the lasting influence of the eruption of the ferment of ideas that had been more or less forced undercover during the Occupation, and of the high spirits that burst forth even under the difficult circumstances that followed.

- Left Bank: Art, Passion and the Rebirth of Paris 1940-1950 by Agnès Poirier (Bloomsbury, £25)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Shon Faye: Love in Exile review - the greatest feeling

Love comes under the microscope in this heartfelt analysis of the personal and political

Shon Faye: Love in Exile review - the greatest feeling

Love comes under the microscope in this heartfelt analysis of the personal and political

Add comment