All Too Human, Tate Britain review - life in the raw | reviews, news & interviews

All Too Human, Tate Britain review - life in the raw

All Too Human, Tate Britain review - life in the raw

Bacon and Freud dominate but don't overwhelm in a fleshy century of painting

Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud are here to draw in the crowds, but also to set the tone of a Tate Britain exhibition that explores the equivalence of flesh and paint in depictions of the body that even at their most tender and sensual rarely stray far from the brutal and disturbing.

Stanley Spencer is a canonical figure now, but he was a source of embarrassment only a generation or so ago when his paintings, which had to go somewhere, occupied a staircase leading to the Tate Gallery’s lavatories. Here he is feted as a seminal figure, alongside Sickert, Soutine, and even David Bomberg, whose reputation has finally been secured this year by a long overdue retrospective. In a chronological arrangement that takes us through artists either working, or simply influential in Britain from the early 20th century to now, these four are presented as pioneers of an art dealing in the physical and psychological sensations of being alive, in all the mundane and glorious complexity that implies.

Spencer’s portraits of Patricia Preece present the body, even the adored body of a lover, as a site of mixed responses and impulses. A portrait from 1933 (pictured right) confronts us with a frankly unlovely face, and yet harshly described bulging eyes and a wonky mouth soon meet the pearly skin of neck and shoulders, the dark recess of collarbone as it disappears beneath fabric a place of palpable erotic charge.

Spencer’s portraits of Patricia Preece present the body, even the adored body of a lover, as a site of mixed responses and impulses. A portrait from 1933 (pictured right) confronts us with a frankly unlovely face, and yet harshly described bulging eyes and a wonky mouth soon meet the pearly skin of neck and shoulders, the dark recess of collarbone as it disappears beneath fabric a place of palpable erotic charge.

Landscapes by David Bomberg and Chaïm Soutine, pulsing with expressive force, introduce influences beyond the purely figurative, and certainly some of the exhibition’s most intense evocations of human presence are found in London cityscapes by Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach, both of whom were pupils of Bomberg’s at Borough Polytechnic. As well as acknowledging the influence of a painter whose work the critic David Sylvester described as “the finest, by a long way the finest, English painting of its time”, the inclusion of Bomberg introduces an enriching counter-narrative. William Coldstream was Professor of Fine Art at the Slade in the Fifties, his coolly empirical approach to painting from life discernible in the work of students and associates including Euan Uglow and Lucian Freud. At approximately the same time, Bomberg, a misfit and outsider, who had taken up the only teaching post he could find, was instilling in his devoted band of students an approach quite at odds with that of Coldstream. Dismissive of academic, observational rigour, Bomberg sought, in his own cryptic phrase, “the spirit in the mass”, with visual likeness of secondary importance to the intangible essence of an object as it is experienced.

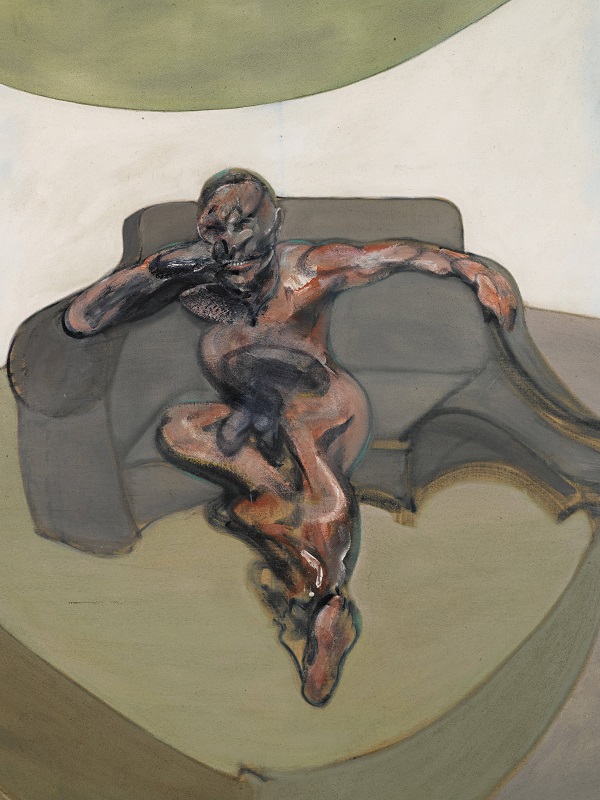

There are neat connections made through the hang, which although often apparently incidental lend a persuasive depth to the show’s narrative. Landscapes placed side by side make vividly apparent the reasons why in 1955 a critic wrote that Bomberg "might have been our English Soutine". The very presence of Soutine and Giacometti goes some way to dislodging the isolated status habitually accorded to Freud and Bacon, who tend to be connected more closely with each other, and to historical antecedents than to the contemporary European art scene (pictured left: Francis Bacon, Portrait, 1962). For all the value of considering Bacon alongside Giacometti, their distortions of the human figure presented as evidence of a shared project born out of the anxieties of their age, Giacometti is a conspicuous oddity as the show's lone sculptor.

There are neat connections made through the hang, which although often apparently incidental lend a persuasive depth to the show’s narrative. Landscapes placed side by side make vividly apparent the reasons why in 1955 a critic wrote that Bomberg "might have been our English Soutine". The very presence of Soutine and Giacometti goes some way to dislodging the isolated status habitually accorded to Freud and Bacon, who tend to be connected more closely with each other, and to historical antecedents than to the contemporary European art scene (pictured left: Francis Bacon, Portrait, 1962). For all the value of considering Bacon alongside Giacometti, their distortions of the human figure presented as evidence of a shared project born out of the anxieties of their age, Giacometti is a conspicuous oddity as the show's lone sculptor.

Michael Andrews, another artist only recently recovered from the sidelines, is represented here through three paintings, including one of The Colony Room, the Soho drinking club favoured, notably, by Bacon, Freud and the photographer John Deakin. The painting serves as a pivot around which to gather a whole cast of disparate characters associated with that place, and in doing so draws together the narrative tendencies of a much wider group of artists including Andrews, RB Kitaj and Paula Rego, for example, with the existential concerns of Bacon and Freud, whose focus on the isolated human figure tends to set them apart. The Colony Room I, 1962, immerses us in the ebb and flow of a crowded room, partially registered faces contorted by the demands of social interaction. It's a painting that immerses us in the intense loneliness of social discourse, just as Freud's single figures impose on us an uncomfortable familiarity, a bond even, with individuals isolated and scrutinised. The many connections brought about through an intelligent hang make this a truly thought-provoking show, but the headline artists are solidly represented too, enough to satisfy visitors keen to simply take their fill of Bacon and Freud.

- All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life at Tate Britain until 27 August

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment