Francis Bacon: A Brush with Violence, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

Francis Bacon: A Brush with Violence, BBC Two

Francis Bacon: A Brush with Violence, BBC Two

Portrait of the artist as disaster area

Francis Bacon died in April 1992, aged 82, but heaven knows how he managed to live that long.

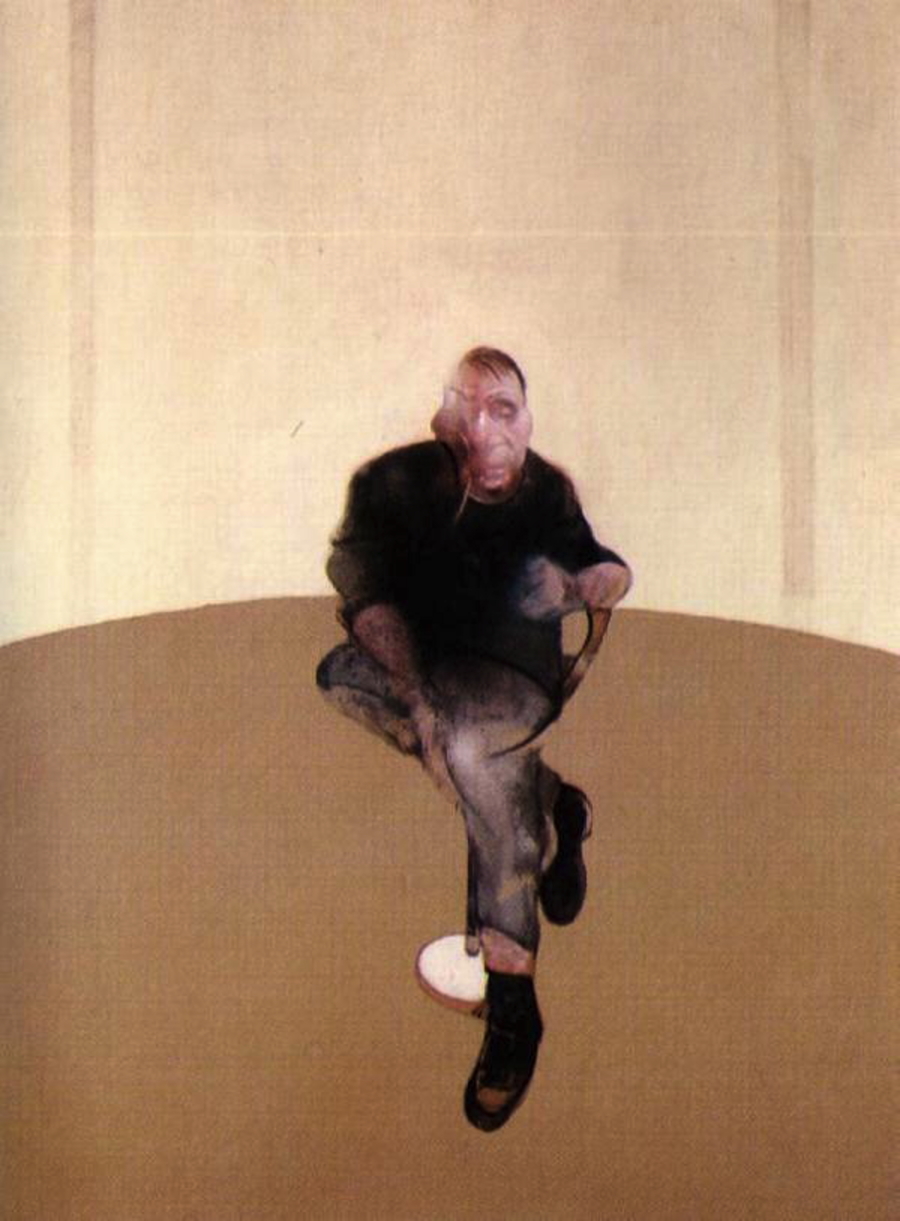

The film lit the blue touch paper by looking at Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, which, when exhibited in London in 1945, did little to enhance any sense of euphoria at the prospect of a Nazi-free world. Critics and public were shaken by Bacon’s ghastly, misshapen figures, which may look to us now like antecedents of HR Giger’s appalling Alien. Nonetheless, it was clear that a major talent was on the loose, and horror and pain would become familiar traits in his work (below, panel from Bacon's Study for a Self-Portrait – Triptych, 1985-86).

He ended up for a time in Weimar Berlin, chaperoned by an exploitative bisexual friend of his father, then moved to Paris, where a Picasso exhibition made a deep impression on him. Back in London, he moved into John Everett Millais’s old house in South Kensington (partially bombed), where he held riotous gambling parties and was attended by his childhood nanny, Jessie Lightfoot. Although blind and forced to sleep on the kitchen table, Nanny Lightfoot diligently supplied visitors with cannabis.

Though we saw scenes of the convivial, bon viveur Bacon (bearing an odd resemblance to Dudley Moore), sometimes babbling enthusiastically in fluent though thoroughly Anglified French, his emotional life was driven by his masochistic urges. He fell into an arduous love affair with ex-Spitfire pilot and sadist Peter Lacy, who beat him mercilessly and (as one contributor recalled) once hurled the artist through a second-floor window. In later years he became infatuated with George Dyer, an East End criminal and acquaintance of the Krays, but instead of the brutal, dominant lover Bacon wanted, the disappointing Dyer was a borderline alcoholic who suffered from erectile dysfunction.

Yet Dyer’s suicide in Paris in 1971, as Bacon launched a major exhibition at the Grand Palais, shocked the artist deeply, and prompted some of his most powerful work including the “Black Triptychs”, which fixated on the Dyer suicide in agonising close-up. Artist and friend Maggi Hambling (pictured above), in one of several astute comments, noted how it was almost considered “a dirty habit” to go and look at Bacon’s paintings, and also pointed out how he defied the prevailing tides of abstract expressionism and “American stuff” to concentrate on depictions of the human body. Bacon’s instinct proved unerring, as his legacy of screaming popes and crucifixion scenes, Figure with Meat, the Study for a Self-Portrait – Triptych, 1985-86 and his sequence of late landcapes attests.

Yet Dyer’s suicide in Paris in 1971, as Bacon launched a major exhibition at the Grand Palais, shocked the artist deeply, and prompted some of his most powerful work including the “Black Triptychs”, which fixated on the Dyer suicide in agonising close-up. Artist and friend Maggi Hambling (pictured above), in one of several astute comments, noted how it was almost considered “a dirty habit” to go and look at Bacon’s paintings, and also pointed out how he defied the prevailing tides of abstract expressionism and “American stuff” to concentrate on depictions of the human body. Bacon’s instinct proved unerring, as his legacy of screaming popes and crucifixion scenes, Figure with Meat, the Study for a Self-Portrait – Triptych, 1985-86 and his sequence of late landcapes attests.

In the end, could some sort of salvation be dragged from the wreckage? Hambling suggested that “his work can be seen as a search for God,” while art critic John Richardson reckoned that Bacon is now seen “almost as a religious painter”. He certainly wouldn’t have been deterred by the prospect of flagellation and crucifixion.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment