Victorian Giants, National Portrait Gallery review - pioneers of photography | reviews, news & interviews

Victorian Giants, National Portrait Gallery review - pioneers of photography

Victorian Giants, National Portrait Gallery review - pioneers of photography

Artistic searches, technical advances fuel the discoveries of the Victorian age

It is a very human crowd at Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography. There are the slightly melancholic portraits of authoritative and bearded male Victorian eminences, among them Darwin, Tennyson, Carlyle and Sir John Herschel.

From the discovery of photography, at some point in the late 1820s, with the chemical fixing on a paper, glass or metal surface of a world observed through mechanical lenses, the new medium embraced any scientific advance that came its way, vastly accelerating its progress until it became the mass medium that we know today. But in the 19th century, photography must have seemed as astonishing to its practitioners and audience then as digital does to us today. Technology is not always an advance, however, and photography’s relation to art was always complicated: historical photography’s detailed beauties are now subsumed into digital, which does not approach as yet the aesthetic quality of such earlier forms.

For the quartet of artists at Victorian Giants, it was the wet collodion method of developing negatives and also albumen prints invented in the 1850s – there is an excellent show-and-tell video in the show – that enabled the creation of these images. The processes and materials were elaborate and painstaking, as careful as the relatively long exposures required in early photography that is vital for understanding the careful thought behind the images: we are decades before the ability to take snapshots, although manipulation in the darkroom is as old as photography.

For the quartet of artists at Victorian Giants, it was the wet collodion method of developing negatives and also albumen prints invented in the 1850s – there is an excellent show-and-tell video in the show – that enabled the creation of these images. The processes and materials were elaborate and painstaking, as careful as the relatively long exposures required in early photography that is vital for understanding the careful thought behind the images: we are decades before the ability to take snapshots, although manipulation in the darkroom is as old as photography.

The work of these four artists offers a fascinating insight into the visual preoccupations of 19th century Britain. They were, in different ways, at the heart of the establishment: photography was expensive at the time, and required other necessities not given to all, such as suitable premises, and lots of time. The new medium had royal approval, with Prince Albert himself pioneering its potential as a reproductive medium to bring the images of great art – painting and sculpture – to the masses, while the royal couple themselves commissioned work. (The NPG has cleverly worked with its new patron the Duchess of Cambridge, an enthusiastic photographer herself, to publicise this exhibition.) These photographers was relatively privileged. Only the mysterious Swedish emigré Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875) would be called a professional. Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was one of the famous Pattle sisters, and took up photography in her 40s, encouraged by her family desperate that she use up some of her inexhaustible energy, and turn her domestic scrutiny outwards (top picture, Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty, 1866). She went on not only to have her work collected from the 1850s by the Victoria and Albert Museum, but to act effectively as the museum’s first photographer in residence.

These photographers was relatively privileged. Only the mysterious Swedish emigré Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875) would be called a professional. Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was one of the famous Pattle sisters, and took up photography in her 40s, encouraged by her family desperate that she use up some of her inexhaustible energy, and turn her domestic scrutiny outwards (top picture, Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty, 1866). She went on not only to have her work collected from the 1850s by the Victoria and Albert Museum, but to act effectively as the museum’s first photographer in residence.

Clementina, Lady Hawarden (1822-1865) photographed her family, in particular her daughters, not a stone’s throw from the new museum. She has only relatively recently been rediscovered, with a V&A exhibition some 20 years ago, to enter the ever-expanding canon of significant photographers (pictured below, Photographic Study (Clementina and Isabella Grace Maude, 1863-4). Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), the Oxford mathematics don world famous as the author of Alice in Wonderland, has received a lot of attention for his passion for photography, some of it suspicious because of his frequent choice of pre-pubescent girls as subjects (although they were almost invariably chaperoned: main picture, Alice Liddell, 1858)

This fascinating quartet all knew each other, and all were taught to a varying degree by Rejlander. There is an 1857 self-portrait by Lewis Carroll – what a hair-do! – and a portrait of Carroll from six years later with even more elaborate curls, his expression wistful as he almost caresses a camera lens, by Rejlander. The group moved in intersecting circles: both Cameron and Carroll photographed the young Ellen Terry, who was briefly married to the artist GF Watts, 30 years her senior, with both part of the Holland House set that was at the centre of English intellectual and political life. Cameron photographed Watts too, and also depicted Alice Liddell in the guise of various mythical characters.

This fascinating quartet all knew each other, and all were taught to a varying degree by Rejlander. There is an 1857 self-portrait by Lewis Carroll – what a hair-do! – and a portrait of Carroll from six years later with even more elaborate curls, his expression wistful as he almost caresses a camera lens, by Rejlander. The group moved in intersecting circles: both Cameron and Carroll photographed the young Ellen Terry, who was briefly married to the artist GF Watts, 30 years her senior, with both part of the Holland House set that was at the centre of English intellectual and political life. Cameron photographed Watts too, and also depicted Alice Liddell in the guise of various mythical characters.

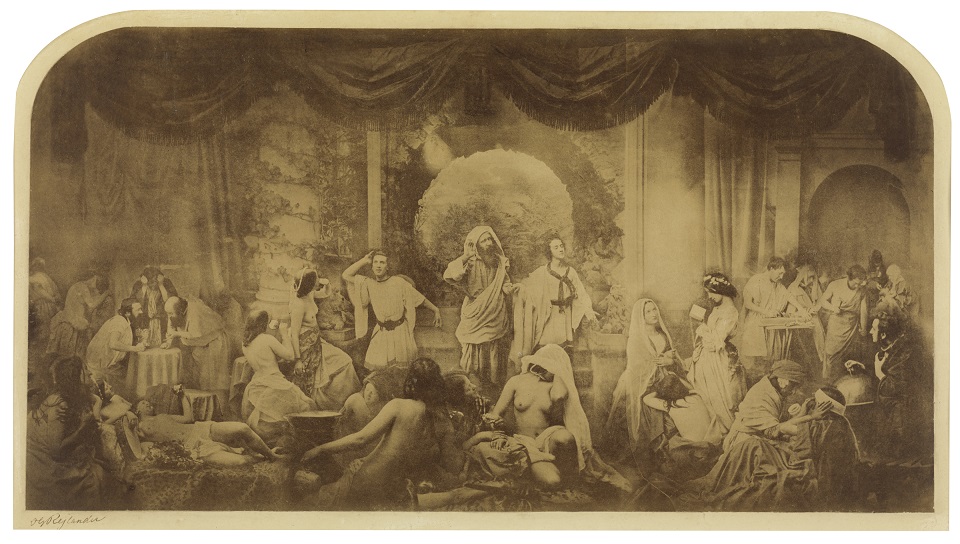

Some of their work seems to our taste now risibly melodramatic. Myth brings out the worst – Rejlander’s The Evening Sun (Iphigenia) – even more so especially when the photographer attempts an ensemble that is imitative of Renaissance composition. Rejlander’s Two Ways of Life (centre picture) is beloved because of his innovative combinations of some 30 negatives (he has been nicknamed the father of Photoshop). Its rather outlandish human spectacle certainly pre-empts Cecil B DeMille and epic silent movies, now appearing endearingly ridiculous. Yet he can use existing paintings to advantage in a rather straightforward Non Angeli sed Angli (Not Angels but English) image of two plump-faced baby angels lifted directly from the winged cherubs of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna.

Anonymous servants, family members, friends and acquaintances were also pressed into acting as models for mythological characters, riffing on the knowledge of the classics that these Victorians could almost take for granted. This exhibition seamlessly presents two contrasting sides to Victorian preoccupations: the acting out of classical myths, and the passion for portraying real people. The mythical poses may seem now a tad too melodramatic, but the incisive thoughtful portraits of real people make for an informative and captivating exhibition.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment