The London Mastaba, Serpentine Galleries review - good news for ducks? | reviews, news & interviews

The London Mastaba, Serpentine Galleries review - good news for ducks?

The London Mastaba, Serpentine Galleries review - good news for ducks?

Rockstar artist’s floating oil drums provoke questions around the purpose of public art

It’s not as immersive as New York’s The Gates, 2005, nor as magnificent as Floating Piers, 2016, in Italy’s Lake Iseo – it has also, according to Hyde Park regular Kay, “scared away the ducks,” – but superstar artist Christo’s The London Mastaba looks quite absurdly unreal and is totally free for the public.

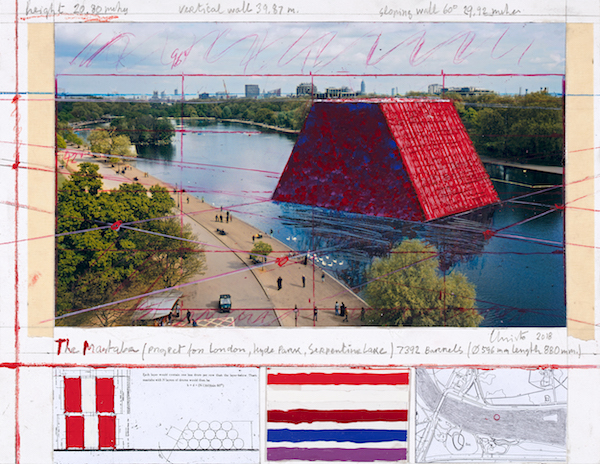

Constructed with 7,506 brightly painted oil barrels, the 600 tonne sculpture – which is shaped as and named by the bench found outside ancient Mesopotamian houses – floats like a serene 3D gif between bridge, lido and island. The Serpentine Gallery's synchronous exhibition on Christo and Jean-Claude’s work (also free) tracks how the initial use of tin cans became the larger oil drums and how early projects such as Wall of Barrels – The Iron Curtain, 1962, which barricaded the rue Visconti in Paris a year after the Berlin Wall went up, and the never-realised Ten Million Oil Barrel Wall, 1967, which was intended to link both sides of the Suez Crisis following the Six-Day War, were overtly political architectural-artistic interventions intended for the public space.

It also shows how the London Mastaba emerged from an unrealised million-barrel mastaba project for Houston, Texas, and may be a precursor for a 150m high one at the edge of Liwa Oasis, Abu Dhabi. In this light, it suffers the littleness of being a less committed version of these other megaliths – because thousands of stacked oil drums shimmering with Texan heat or towering over a road-scarred desert have a different kind of resonance to when they are floating on top of the Serpentine. But under the changeable London sky the ruffled lake surface trembles with the reflections of the painted barrels, yoking together river bed, water, art work and sky into a slick perpetual dance. The intended effect isn’t always apparent but when it is, the very strangeness of the installation is powerful enough, the assimilation of disparate parts alluring, and its mass and colour irrefutable.

Around the park, people aged from six to grandparent remark how much it looks like a slide (“It makes me feel fun,” says Noah (7) tucking into chicken nuggets) and while the penny-sweet colours fizz gently against greenery they also definitively block out the few buildings which peek above the canopy surrounding the park. How restful that Westminster disappears behind pink and blue dots! How easeful that the towers of Kensington and Hyde Park Corner are erased. London’s summer park culture is gloriously louche, mixed and frequently semi-naked, and the Mastaba becomes the Serpentine’s very own carnivalesque navel. The ancient Mesopotamian bench was intended as a place for visitors to rest a while – a built metaphor betokening hospitality. To walk the lake’s perimeter then, is to encounter this inscrutable floating mass at every step and to entertain its playfulness, perhaps thoughtfully.

Around the park, people aged from six to grandparent remark how much it looks like a slide (“It makes me feel fun,” says Noah (7) tucking into chicken nuggets) and while the penny-sweet colours fizz gently against greenery they also definitively block out the few buildings which peek above the canopy surrounding the park. How restful that Westminster disappears behind pink and blue dots! How easeful that the towers of Kensington and Hyde Park Corner are erased. London’s summer park culture is gloriously louche, mixed and frequently semi-naked, and the Mastaba becomes the Serpentine’s very own carnivalesque navel. The ancient Mesopotamian bench was intended as a place for visitors to rest a while – a built metaphor betokening hospitality. To walk the lake’s perimeter then, is to encounter this inscrutable floating mass at every step and to entertain its playfulness, perhaps thoughtfully.

But public art is arranged by individuals and a photograph of Hans Ulrich Obrist pasted onto one of the collaged London Mastaba plans in the exhibition provokes a ripple of unease for its coterie in-joke chumminess. Is this art genuinely in service of the public or merely servicing the institutions involved? The answer, of course, is a mix of both – but while Serpentine Galleries Chairman (and ex New York Mayor) Michael Bloomberg is clear that “the benefits that art brings to cities aren’t always recognised,” he is equally clear that quantitative benchmarks on the civic worth of art (how much extra revenue the Mastaba brings to the already tourist-saturated businesses round the park) outweigh the platitudinous qualitative catch-all about “bringing diverse communities together.” Yet most artworks can do that – it's merely a matter of curatorial effort.

That said, there is genuine effort behind this installation. As with all his other projects, the £3m cost is borne by Christo and defrayed through selling artworks, and attention has been paid to the afterlife of the piece: once the sculpture is dismantled its unrented components will be recycled and the lake will receive ecological improvements to encourage biodiversity and prevent algal bloom (good news for the ducks). And while the (now obligatory) mobile app explaining the work is touted as a way of connecting people, it’s actually the jolly gallery staff cannily stationed round the park who really get visitors talking.

That said, there is genuine effort behind this installation. As with all his other projects, the £3m cost is borne by Christo and defrayed through selling artworks, and attention has been paid to the afterlife of the piece: once the sculpture is dismantled its unrented components will be recycled and the lake will receive ecological improvements to encourage biodiversity and prevent algal bloom (good news for the ducks). And while the (now obligatory) mobile app explaining the work is touted as a way of connecting people, it’s actually the jolly gallery staff cannily stationed round the park who really get visitors talking.

Should public art find its main justification in not coming out of public budgets? It’s great when it happens, but absolutely not. Should there be active efforts to engage all kinds of people who might otherwise not? For sure. Should you pay attention to my judgment of the London Mastaba? Up to you. The exhibition is cleanly curated, informative and gloriously free; the sculpture is magnificently weird and very definitely there. Both are worth a look. But it’s public art and the true measure of its success is its reception. “Any interpretation is important,” Christo remarked at its unveiling – but Instagram post or talking point? Skin or substance? It makes a big difference.

- The London Mastaba will float on the Sepentine until 23 September; the exhibition Christo and Jean-Claude: Barrels and the Mastaba will be at the Serpentine Galleries until 9 September 2018, both free

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment