Romeo and Juliet, Barbican review - plenty of action but not enough words | reviews, news & interviews

Romeo and Juliet, Barbican review - plenty of action but not enough words

Romeo and Juliet, Barbican review - plenty of action but not enough words

Erica Whyman's RSC production finds youthful energy but not clarity

It’s clear from the start – from a Prologue that quickly dissolves familiar rhythms and words into a Babel of clamour and sound.

Tom Piper’s set is an unprepossessing thing. A giant concrete cube revolves in the centre of a uniformly grey-brown space – urban at its most generic – and only a distant slither of greenery for Friar Lawrence’s cell offers any variation. It’s all self-consciously spare, an empty playground for this young cast (supplemented with students from local schools) to clamber over and run around to the accompaniment of throbbing dance music.

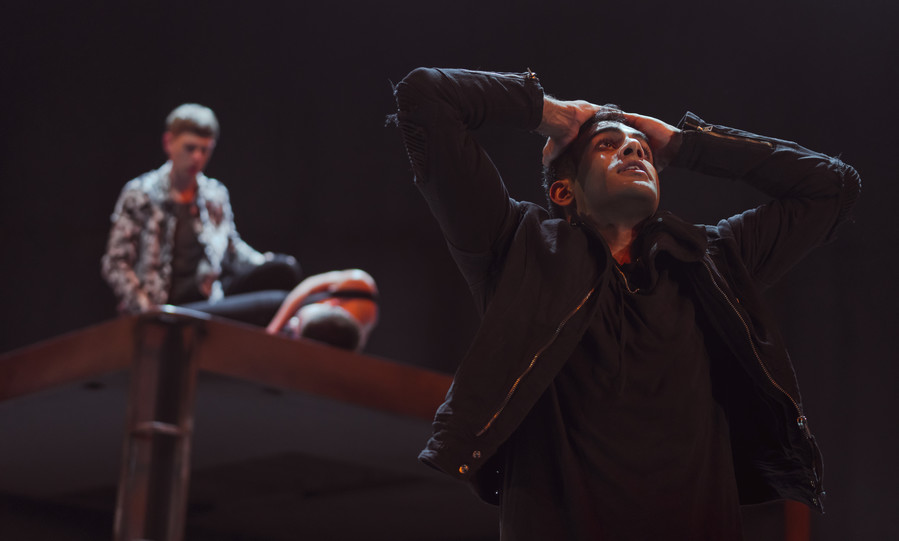

But the games played here are far from childish. Violence is always in view. Everyone in this dystopian Neverland – even the mothers – carries a knife, and stabbings become the punctuation to every war of words; wounds are fleshy full stops, carved into the body. In a week where knife crime is on the front page, a year in which unprecedented numbers of teenagers are dying on London’s streets, it feels like a natural part of the conversation, even if it’s not a contribution that gets us much further.The production is at its best with the young. Bally Gill’s Romeo (pictured above) is an impetuous hot-head, quick to love and even quicker to lash out, but endearingly self-aware, seen in some lovely gestures of self-dramatising at the start. His streetwise swagger is neatly punctured by Karen Fishwick’s ingenuous Juliet – more child than woman, even by the end. Her struggles against a system (and a script) loaded against her come into focus in a startling confrontation with Michael Hodgson’s erratic Capulet. We see in his nervy, instinctive violence the image of a Romeo or a Mercutio in adulthood, passionate beliefs fossilised into entitlement, anger into tyrannical authority.

But the games played here are far from childish. Violence is always in view. Everyone in this dystopian Neverland – even the mothers – carries a knife, and stabbings become the punctuation to every war of words; wounds are fleshy full stops, carved into the body. In a week where knife crime is on the front page, a year in which unprecedented numbers of teenagers are dying on London’s streets, it feels like a natural part of the conversation, even if it’s not a contribution that gets us much further.The production is at its best with the young. Bally Gill’s Romeo (pictured above) is an impetuous hot-head, quick to love and even quicker to lash out, but endearingly self-aware, seen in some lovely gestures of self-dramatising at the start. His streetwise swagger is neatly punctured by Karen Fishwick’s ingenuous Juliet – more child than woman, even by the end. Her struggles against a system (and a script) loaded against her come into focus in a startling confrontation with Michael Hodgson’s erratic Capulet. We see in his nervy, instinctive violence the image of a Romeo or a Mercutio in adulthood, passionate beliefs fossilised into entitlement, anger into tyrannical authority.

The role of women in Whyman’s gender-blind world (five principal roles, Mercutio chief among them, are switched) is oddly uncertain. Charlotte Josephine’s fists-and-foul-mouth Mercutio (pictured above) feels overworked and ill at ease, unsettled by some awkward verse-speaking that robs the role of its eloquence without offering much in return. Beth Cordingly’s Escalus is better – a figure of embattled female authority and reason in a man’s world. More interesting than either though is Josh Finan’s Benvolio, quietly heartsore for his charismatic cousin, outmanned even by a female Mercutio.

The role of women in Whyman’s gender-blind world (five principal roles, Mercutio chief among them, are switched) is oddly uncertain. Charlotte Josephine’s fists-and-foul-mouth Mercutio (pictured above) feels overworked and ill at ease, unsettled by some awkward verse-speaking that robs the role of its eloquence without offering much in return. Beth Cordingly’s Escalus is better – a figure of embattled female authority and reason in a man’s world. More interesting than either though is Josh Finan’s Benvolio, quietly heartsore for his charismatic cousin, outmanned even by a female Mercutio.

The energy here is right, the emotion too. But in sacrificing verse for action, offering us the generalised sense of every speech rather than the space and clarity to grasp the specifics, Whyman gives us a Romeo and Juliet that is too literal. Her teenagers need knives because they can’t use their words. Shakespeare’s need knives because words – even his words – are simply not enough. That’s the real tragedy, and that’s what we miss here.

- Romeo and Juliet is at the Barbican until 19 January, 2019

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

@AlexaCoghlan

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue