Downstate, National Theatre review - controversial but also clear-eyed and compassionate | reviews, news & interviews

Downstate, National Theatre review - controversial but also clear-eyed and compassionate

Downstate, National Theatre review - controversial but also clear-eyed and compassionate

Bruce Norris's ever-provocative play puts people first, labels second

"Some monsters are real," notes a retribution-minded wife (Matilda Ziegler) early in Downstate, Bruce Norris's beautiful and wounding play that has arrived at the National Theatre in the production of a writer's dreams.

A co-commission and co-production with Chicago's invaluable Steppenwolf Theatre company, where the play premiered last autumn with an Anglo-American cast amidst worries that some might find its content to be too much, Downstate couples Norris's ongoing interest in pushing the topical envelope with a compassion one might not necessarily expect from a dramatist best known for his much-prized Clybourne Park.

At first, one is presumably on the side of the (unseen) community surrounding this gathering of putative undesirables, a quartet regularly subjected to multiple forms of abuse – so much so that they keep a baseball bat by the door just in case. (As the play opens, they are being isolated still further, which will make shopping and transport that much more difficult.) But without for a moment soft-pedalling the brutality or lasting scars left by their actions, the playwright insists on these men as worthy at the very least of a hearing, at least for as long as we can be said to be part of the collective known as humankind (which, admittedly, in Trump's America looks less easy by the day).

At first, one is presumably on the side of the (unseen) community surrounding this gathering of putative undesirables, a quartet regularly subjected to multiple forms of abuse – so much so that they keep a baseball bat by the door just in case. (As the play opens, they are being isolated still further, which will make shopping and transport that much more difficult.) But without for a moment soft-pedalling the brutality or lasting scars left by their actions, the playwright insists on these men as worthy at the very least of a hearing, at least for as long as we can be said to be part of the collective known as humankind (which, admittedly, in Trump's America looks less easy by the day).

Carefully and across two acts whose determined naturalism marks something of a contrast with Norris's style to date, we glean the specifics that have brought these men to this place. The Bible-spouting Gio (Glenn Davis) proffers abundant good cheer to all who are ready to receive it and is counting the months until he can exist back in the world, away from the older housemates whose past actions, in his view, are beyond the pale.

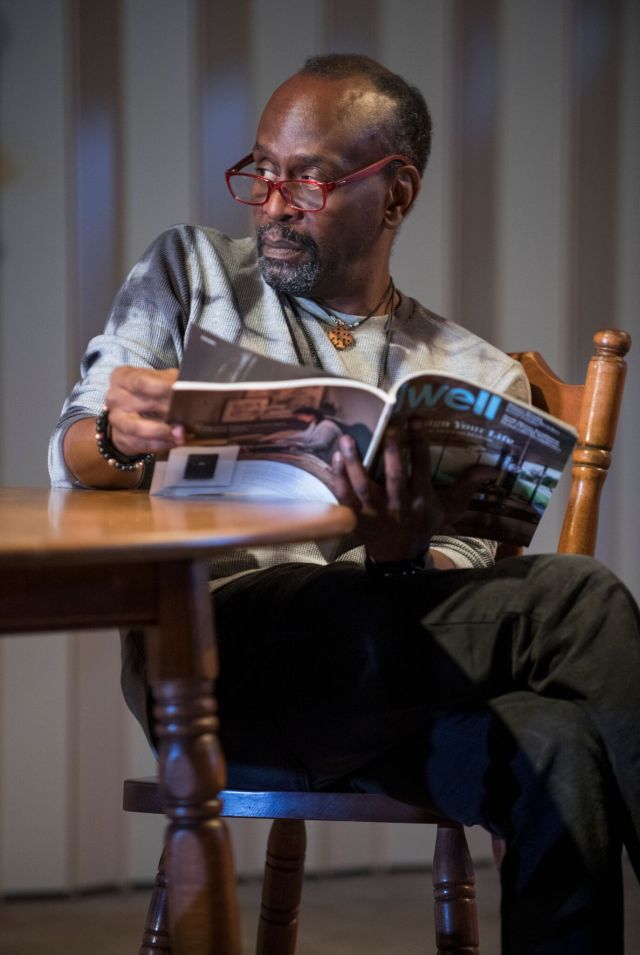

While Gio's is a statutory offense with an adolescent who he thought was of age at the time, the tearful Felix (Eddie Torres) has mistaken love for his young daughter with sexual attraction. The senior generation is represented – thrillingly so in these Steppenwolf actors' indelible performances – by the wheelchair-bound, Chopin-loving Fred (Francis Guinan), who speaks a sort of babyish patois like "shooty shoot shoot", and Dee (K Todd Freeman, pictured above), a onetime dancer who had an affair with an underage cast member in a touring production of Peter Pan. The 14-year-old's role at the time was a Lost Boy (indeed) by the name of Toodles.

The outside world, so to speak, comes to offer recrimination, judgment, or sometimes not. We first glimpse Fred in combative conversation with one of his victims, the now-grown Andy (Tim Hopper), whose wife Em (Ziegler, pictured below with Hopper) feels emboldened on her husband's behalf by the #MeToo movement. Deflecting a degree of vitriol that he seems unable to absorb, Fred is confronted anew after the interval with Andy, who arrives solo ostensibly to retrieve a forgotten phone. That exchange enfolds within it the reason for Fred's immobility in a speech for the ages which also turns Downstate on its axis. Further complicating matters of right and wrong is Dee's de facto presence as his friend Fred's best advocate, Dee quick to argue to anyone who will listen that there is no such thing as "death by blow job". (Other lines from the play are less readily quoted.)  Returning to the auditorium where she arched a comically roof-raising eyebrow or two in Nine Night, the English actress Cecilia Noble is even better here as a parole officer called Ivy possessed of a keen morality who nonetheless can't help but see the men in her charge in the round. Funny when necessary (her line about the family labrador is a darkly comic classic), Ivy exists as a bridge between the men's widening physical isolation and the psychic self-isolation that they will clearly carry with them to the end.

Returning to the auditorium where she arched a comically roof-raising eyebrow or two in Nine Night, the English actress Cecilia Noble is even better here as a parole officer called Ivy possessed of a keen morality who nonetheless can't help but see the men in her charge in the round. Funny when necessary (her line about the family labrador is a darkly comic classic), Ivy exists as a bridge between the men's widening physical isolation and the psychic self-isolation that they will clearly carry with them to the end.

Small wonder, in context, that the altogether rending final passage puts one in mind of Chekhov in its suggestion of sleep and rest as possibly the only final salvation. Downstate isn't perfect: a few moments betray the author's hand, as if Norris is carefully parcelling out his own arguments amongst his characters. And while I remain grateful for the bursts of levity, one or two feel unearned, as if the playwright doesn't quite trust his own expert conversational ebb and flow to vary the mood. Yet as so often with this writer, he is gifted with a director in Pam MacKinnon who shares his clear-eyed embrace and who ensures that the beats land, large and small, whether that means Dee memorialising Diana Ross's screen turn in Lady Sings the Blues or Fred nursing a Chopin disc with the tender embrace he might in another life have extended to a child. You exit Downstate bruised, yes, but oddly blessed as well to be in such achingly empathic company: there are no monsters here, just fallible, flawed, simultaneously fearsome and fearful men.

- Downstate at the National Theatre/Dorfman to 27 April

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Add comment