Van Gogh and Britain, Tate Britain review - tenuous but still persuasive | reviews, news & interviews

Van Gogh and Britain, Tate Britain review - tenuous but still persuasive

Van Gogh and Britain, Tate Britain review - tenuous but still persuasive

The artist's London years provide an insight into his inner life

Soon after his death, Van Gogh’s reputation as a tragic genius was secured. Little has changed in the meantime, and he has continued to be understood as fatally unbalanced, ruled by instinct not intellect.

Van Gogh was a voracious reader with a surprising appetite for Victorian novels and particularly Dickens, whose books he read from boyhood, both in English and in translation. He moved to London in 1873 aged 20 to work for the art dealer Goupil, and his daily walks from Stockwell and the Oval to his office in Covent Garden immersed him in city life. The famous landmarks of London were there to see, but also the social inequalities, which to a young and sensitive man from the relatively provincial city of The Hague must have struck him much as if he were stepping into the pages of a Dickens novel.

London in the 1870s was ripe for social reform: the first Barnardos home was established in 1870, the same year that compulsory education was introduced for children up to the age of 12. Van Gogh was clearly receptive to these concerns, as he was to popular religion, and in the latter part of his stay in England, having lost his job at Goupil, he tried both teaching and preaching before returning to the Netherlands in 1876 (pictured right: The Prison Courtyard, 1890).

London in the 1870s was ripe for social reform: the first Barnardos home was established in 1870, the same year that compulsory education was introduced for children up to the age of 12. Van Gogh was clearly receptive to these concerns, as he was to popular religion, and in the latter part of his stay in England, having lost his job at Goupil, he tried both teaching and preaching before returning to the Netherlands in 1876 (pictured right: The Prison Courtyard, 1890).

Though Van Gogh did not take up painting until 1880, his experience of London was viewed not just through the prism of literature, but also through art. His job at Goupil took him to galleries and salerooms, his signature in the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s visitor book a tantalising trace of his wanderings. In a superbly well-researched room, a selection of paintings seen by Van Gogh while he was in London gives a vivid sense not only of the artist’s own visual experiences, but of prevailing tastes in the early 1870s. His fondness for the Pre-Raphaelites, and the historical and literary subjects that today are categorised as the most extravagant Victoriana, is unexpected perhaps, though Millais’s bleak Chill October, 1870, is echoed in Van Gogh’s own atmospheric landscapes.

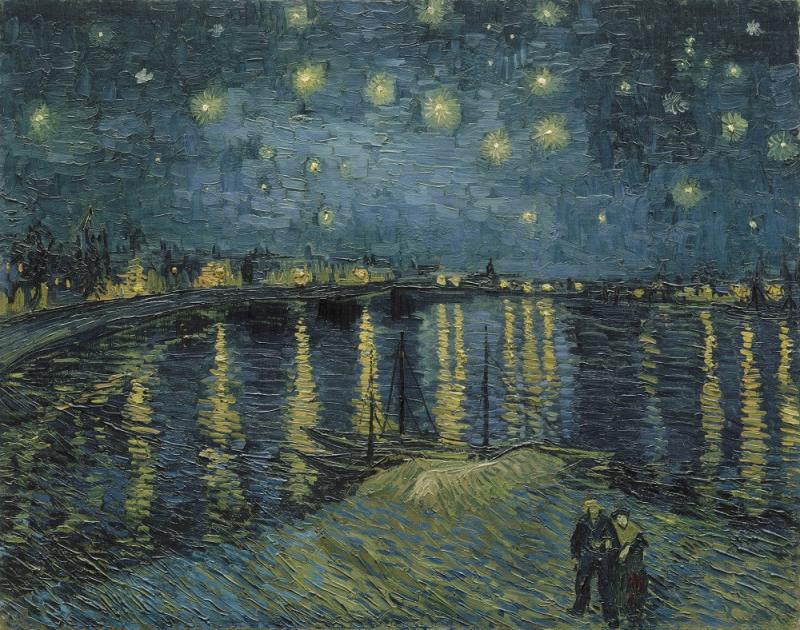

In some cases, Van Gogh kept these works with him by acquiring prints, and his 1882 painting Bleachery at Scheveningen draws heavily on Richard Parkes Bonington’s A Distant View of St-Omer, c.1823, of which Van Gogh had a print. London in the 1870s was at the heart of a thriving market for prints – black and whites, as they were known – and the black and white aesthetic, and a fashion for depicting types, emerges in his early portraits, such as Old Man with Umbrella and Watch, 1882, which though made back in The Hague is persuasively Dickensian in character. Even Van Gogh’s celebrated painting Starry Night, 1888 (main picture), with its pulsating southern sky, is treated here as a memory of London, those streaky lights reflected in the water reminiscent perhaps of gaslights reflected in the Thames. If this connection seems tenuous, it is surely because Van Gogh’s vivid colours and gestural brushstrokes are so far removed from Victorian England that this exhibition triggers an unsettling cognitive dissonance that requires an imaginative leap to resolve. Perhaps this is a hangover from Van Gogh’s late introduction into British cultural consciousness, which only occurred in 1910, 20 years after his death, as part of Roger Fry’s now legendary exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists. It is hard to appreciate now just how significant this exhibition was, but it was sufficiently transformative that Virginia Woolf described its opening as the day “human character changed”.

If this connection seems tenuous, it is surely because Van Gogh’s vivid colours and gestural brushstrokes are so far removed from Victorian England that this exhibition triggers an unsettling cognitive dissonance that requires an imaginative leap to resolve. Perhaps this is a hangover from Van Gogh’s late introduction into British cultural consciousness, which only occurred in 1910, 20 years after his death, as part of Roger Fry’s now legendary exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists. It is hard to appreciate now just how significant this exhibition was, but it was sufficiently transformative that Virginia Woolf described its opening as the day “human character changed”.

Something of its impact, and specifically that of Van Gogh, is marked in a room dedicated to British artists, including Vanessa Bell, Samuel Peploe and Matthew Smith, who all experimented with aspects of his idiosyncratic style, applying vivid colours in bold dashes and sweeps (pictured above: Vanessa Bell, The Vineyard). Van Gogh was by no means the only modernist painter to revive the staid and rather scorned genre of flower painting, but Van Gogh is here credited with its rehabilitation as a subject well-suited to experiments in colour and form, with Christopher Wood’s Yellow Chrysanthemums, 1925, recruited as a homage to Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, 1888. Some of the claims made by this exhibition seem more hopeful than accurate, but the insights are so instructive and thought-provoking that one is inclined to take them in good spirit: for an artist as thoroughly picked over as Van Gogh, this journey through his early years in Britain only reinvigorates the works we thought we knew so well.

- Van Gogh and Britain at Tate Britain until 11 August

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment