Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light, National Gallery review - a national treasure comes to London | reviews, news & interviews

Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light, National Gallery review - a national treasure comes to London

Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light, National Gallery review - a national treasure comes to London

A comprehensive introduction to a little known painter

The National Gallery is on a roll to expand ever further our understanding of western art, alternating blockbusters dedicated to familiar and bankable stars, with selections of work by lesser known figures from across the centuries.

Now it is the turn of the Spaniard Joaquín Sorolla, (1863-1923) billed in 1908 as the "World’s Greatest Living Painter" for an exhibition at London’s Grafton Galleries, the first and last time he was to be shown in Britain. His reception in London was tepid, but in Europe and North America the prizes rained down like confetti and the sales were awesome. He is still adored in Spain, and remains their best loved native painter no matter how little known he is elsewhere.

Here, 60 paintings represent his entire career: portraits of family, friends, fellow artists; social realism; and perhaps above all the beach, the sea, and gardens. He was addicted to light, and to light glinting off the sea, and declared that he wanted to represent nature in reality, and to go beyond conventionality. Born in Valencia, a city drenched in sunlight, Sorolla was orphaned by the age of two and brought up by his uncle and aunt, who recognised his talent early on. By his early thirties he had an international reputation, had travelled and exhibited extensively in Europe, and would conquer America under the auspices of the American millionaire Archer Milton Huntington, founder of the Hispanic Society in New York. He painted the young King of Spain (Alfonso XIII), also the King’s English mother in law, Princess Beatrix, Victoria’s daughter (the only Sorolla in a British national collection) and William Howard Taft, the US President. In his fifties, he was to spend three years on one of the most enormous commissions conceivable, Vision of Spain – fourteen panels, extending 70 metres, of the regions of Spain, all painted in situ on his travels throughout the country, and installed in the Hispanic Society which is the most extensive collection of Hispanic materials outside Spain.

Born in Valencia, a city drenched in sunlight, Sorolla was orphaned by the age of two and brought up by his uncle and aunt, who recognised his talent early on. By his early thirties he had an international reputation, had travelled and exhibited extensively in Europe, and would conquer America under the auspices of the American millionaire Archer Milton Huntington, founder of the Hispanic Society in New York. He painted the young King of Spain (Alfonso XIII), also the King’s English mother in law, Princess Beatrix, Victoria’s daughter (the only Sorolla in a British national collection) and William Howard Taft, the US President. In his fifties, he was to spend three years on one of the most enormous commissions conceivable, Vision of Spain – fourteen panels, extending 70 metres, of the regions of Spain, all painted in situ on his travels throughout the country, and installed in the Hispanic Society which is the most extensive collection of Hispanic materials outside Spain.

Sorolla was a friend to John Singer Sargent, knew Whistler, and was among those artists from Manet on who were passionate not only about the artists of the past but in particular were part of the rediscovery internationally of the wonders of Velázquez, not to mention Goya.

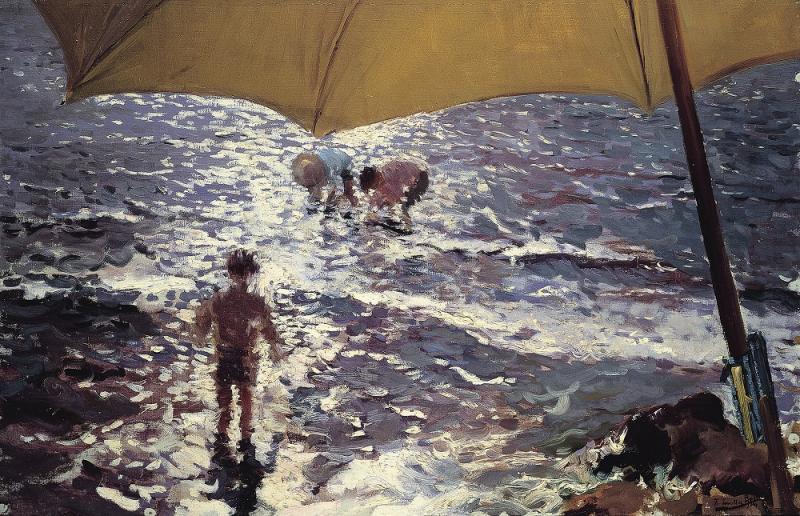

Sorolla seems to have been someone absolutely sure of his vocation. He was a very quick painter who painted his beach scenes en plein air. His 1904 Afternoon at the Beach in Valencia (main picture) frames a trio of playful youngsters in the shallows of the glittering sea with a depiction of the vast umbrella which sheltered the working artist. Other scenes show us young girls running along the beach, boys sunning themselves, a young fisherman with a basket full of silvery fish as glinting in the sun as the ruffled water, fishermen pulling up a small sailing dinghy, a white boat gliding towards us pulled through the water by two exuberant young boys. These paintings are full of the artist's delight in the scenes before him.

Earlier in his career, Sorolla had produced a clutch of social realist paintings, in which the sea featured both as a work place and as a form of therapy. Sad Inheritance shows a host of disabled young boys, brought to bathe in the sea by a monk from their orphanage. And They Still Say Fish is Expensive! using a justifiably dark and shadowy range of colour depicts a badly wounded young fisherman tended by two anxious older men in the hull of their working boat (pictured above). In The Return from Fishing (pictured below) two huge oxen guided by three young men pull a fishing boat onto shore; brilliantly composed with artful diagonals and verticals – sail, boat, beasts, men – dignifies the sheer hard work involved making a living by the sea. Sorolla was a passionately devoted family man, and one of his most imaginative renderings is the vast Madre, where only his wife’s head peeps out from among a swathe of white linens, gazing across at the tiny form of her new born daughter, her hand gently touching the baby. Various portraits of his children hint at the psychological complexity of siblings, but are not quite as fascinating John Singer Sargent’s investigations of families - perhaps Sorolla was just too close to his subjects, his emotions softening insight.

Sorolla was a passionately devoted family man, and one of his most imaginative renderings is the vast Madre, where only his wife’s head peeps out from among a swathe of white linens, gazing across at the tiny form of her new born daughter, her hand gently touching the baby. Various portraits of his children hint at the psychological complexity of siblings, but are not quite as fascinating John Singer Sargent’s investigations of families - perhaps Sorolla was just too close to his subjects, his emotions softening insight.

The paintings which are studies for the awesome Hispanic Society murals are, in the 21st century, simply too quaint and picturesque, illustrations of regional customs rather than interpretations. For subjects chosen by himself there are marvellous highlights in paintings that are both more relaxed and more adventurous: the great gardens in Granada and Seville, vistas of the great curved beach at San Sebastián seen from above, and dashingly exuberant images of his favourite models, his wife and daughters, sitting in the garden dappled with sunlight, having a siesta on the lawn.

Sorolla’s 2009 monographic exhibition was the most popular this century at the Prado, Madrid, but in the context of London’s National Gallery the paintings show him as a major minor master, neither as imaginative nor unexpected enough to rank among the innovators who have changed the way we see the world.

- Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light at the National Gallery until 7 July

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment