Lake Keitele: A Vision of Finland review, National Gallery - light-filled northern vistas | reviews, news & interviews

Lake Keitele: A Vision of Finland review, National Gallery - light-filled northern vistas

Lake Keitele: A Vision of Finland review, National Gallery - light-filled northern vistas

One of the National Gallery's most popular postcards comes under the spotlight

Finland is celebrating its centenary this year and the National Gallery's exhibition of four paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kalela (1865-1931) of a very large lake in central Finland is a beguiling glimpse of the passion its inhabitants attach to its scenic beauty, in winter darkness and here, summer night. Finland possesses almost 190,000 lakes, depending on your definition.

Finland has not been Finland very long: dominated by Sweden for centuries, and a Russian duchy until 1917. Its language is complex and barely related to any other European tongue, its culture except for a handful of architects and designers – its own distinctive art nouveau, the Saarinens, Alvaar Aalto, Marimekko – little known beyond its boundaries. And perhaps because of this history its people are fiercely patriotic.

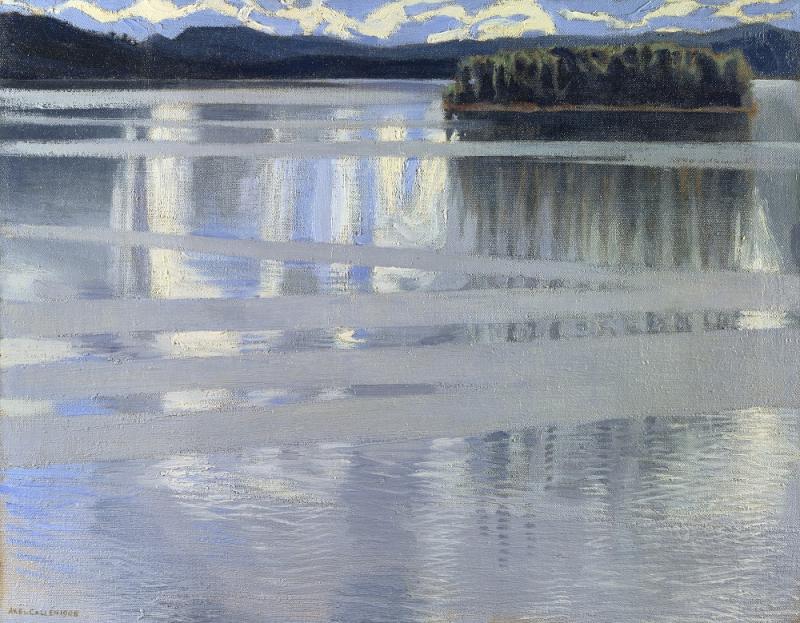

Thus in Anglophone territory the immensely accomplished Gallen-Kalela is little known. This painting of Lake Keitele was bought by the National Gallery in 1999, and has become one of the gallery’s most popular postcards (main picture). But it is even now, despite the renewed attention to Nordic art in general over the past few decades, his only work in a British public collection.

Thus in Anglophone territory the immensely accomplished Gallen-Kalela is little known. This painting of Lake Keitele was bought by the National Gallery in 1999, and has become one of the gallery’s most popular postcards (main picture). But it is even now, despite the renewed attention to Nordic art in general over the past few decades, his only work in a British public collection.

The British, though, are quite addicted to landscapes (the more urban we become) and these light-filled vistas of water and sky are supremely fulfilling in ways that are hard to put into words. The paintings are not meticulously realistic, if my own memories of Finnish lakes and landscapes are accurate, but exceptionally telling in the emotions they evoke, especially in a transcendant response to light. The light crisscrosses the surface of nearly still water in ribbons and pathways while ripples of light in waving horizontals underline broader meandering strokes of light greyish blues, varied whites, the texture of the canvas providing enlivening support. In several views there are tree-filled islands, while on the lake side the land emerges in a series of softly contoured hills, and over all the clouds dance, echoing the dancing water (pictured above right: Lake View, 1901).

A very fine, large-scale pastel from 1915, recently rediscovered, shows a lake festooned with islands, under the softening reddish glow of sunset. The image is curiously poignant, serene and somehow resigned, suggestive of changing light and thus evoking the passage of time. The view is quietly gleaming, misty and shimmering, recalling in mood the kind of pathway from shore to water and back to shore that somehow evokes subtly and quietly the notion of journeys well beyond a single day, stretching far beyond, a visionary journey expressed in what seems simply a skilled rendering of water, land and sky. What comes to mind are other northern views that go beyond the literal and mundane, from Casper David Friedrich to Turner. Gallen-Kallela yearned, he wrote, “for light so powerful that the sun blackens, and for colours that sparkle and explode”. His depictions of the lakes were nurturing and symbolic, the landscapes he found calming in times of stress.

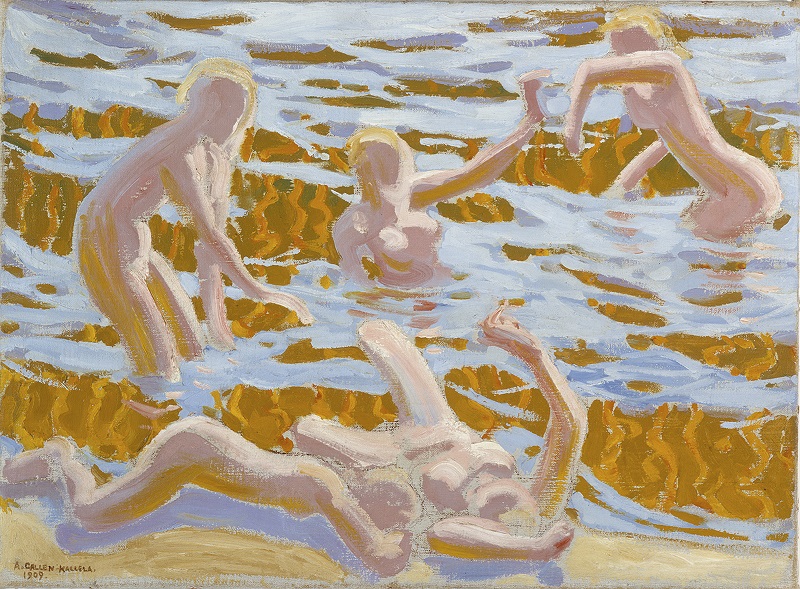

Gallen-Kallela studied art extensively in continental Europe, and spent significant periods studying and working, notably in Paris, and also travelled, unusually, to East Africa. At home he is perhaps better known for his attention to visualising folklore and sagas, notably the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic, written down in the 19th century from oral traditions, ballads and stories narrated down the generations. He was a very fine decorative arts practitioner as well, with many a design to his credit, and also an accomplished maker of furniture. Thus, underlying his landscapes is an exceptionally strong sense of structure, a foundation and composition on which to play with light, texture and colour. He was also an accomplished portraitist when he wished, exploiting awkwardness to fervent effect, but here his several paintings of naked figures in the water, or a boat, are more awkward than secure, and curiously discomforting (pictured above: Oceanides, 1909). But the landscapes where there are no figures evoke a whole range of feelings, an acknowledgement of grandeur and an embracing serenity: somehow we feel at home in a landscape that is both sublime and accessible.

He was also an accomplished portraitist when he wished, exploiting awkwardness to fervent effect, but here his several paintings of naked figures in the water, or a boat, are more awkward than secure, and curiously discomforting (pictured above: Oceanides, 1909). But the landscapes where there are no figures evoke a whole range of feelings, an acknowledgement of grandeur and an embracing serenity: somehow we feel at home in a landscape that is both sublime and accessible.

- Lake Keitele: Visions of Finland at the National Gallery until 4 February 2018

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment