Appropriate, Donmar Warehouse review - fraught family reunion blisteringly told | reviews, news & interviews

Appropriate, Donmar Warehouse review - fraught family reunion blisteringly told

Appropriate, Donmar Warehouse review - fraught family reunion blisteringly told

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s 2013 play is tensely dark, as well as very funny

You can’t fail to feel the ghosts in Appropriate at the Donmar Warehouse: they are there in the very timbers of the ancient Southern plantation house that is the setting for Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s fraught&nb

But Jacobs-Jenkins is surely engaging with another set of ghosts too, those of American drama itself, with the likes of O’Neill, Miller and many more – Tracy Letts and August: Osage County comes particularly to mind – in the way that he subjects this family unit to unforgiving scrutiny. It’s a lineage into which Jacobs-Jenkins fits very well, not least for his sheer command of theatrical form: closely adhering to the dramatic unities, Appropriate concentrates its blistering energy into a cauldron of dysfunctional action that is consistently tight in dramatic structure.  Now 34, Jacobs-Jenkins has a handful of plays behind him – The Octoroon reached the National last year in a transfer from Richmond’s Orange Tree; Gloria was staged at the Hampstead Theatre in 2017 – and he again shows himself here to be a slyly referential writer, who slots a deconstructive postmodern slant into his stories. The Octoroon particularly revealed such a tendency in the way that its treatment of slavery was leavened by subversive engagement with melodrama. Appropriate is similarly self-conscious, exact in its exploitations of timed entrances, concealments and revelations, and incorporating knowingly long speeches that evince an explicit artifice of structure, one that plays perhaps even on farce.

Now 34, Jacobs-Jenkins has a handful of plays behind him – The Octoroon reached the National last year in a transfer from Richmond’s Orange Tree; Gloria was staged at the Hampstead Theatre in 2017 – and he again shows himself here to be a slyly referential writer, who slots a deconstructive postmodern slant into his stories. The Octoroon particularly revealed such a tendency in the way that its treatment of slavery was leavened by subversive engagement with melodrama. Appropriate is similarly self-conscious, exact in its exploitations of timed entrances, concealments and revelations, and incorporating knowingly long speeches that evince an explicit artifice of structure, one that plays perhaps even on farce.

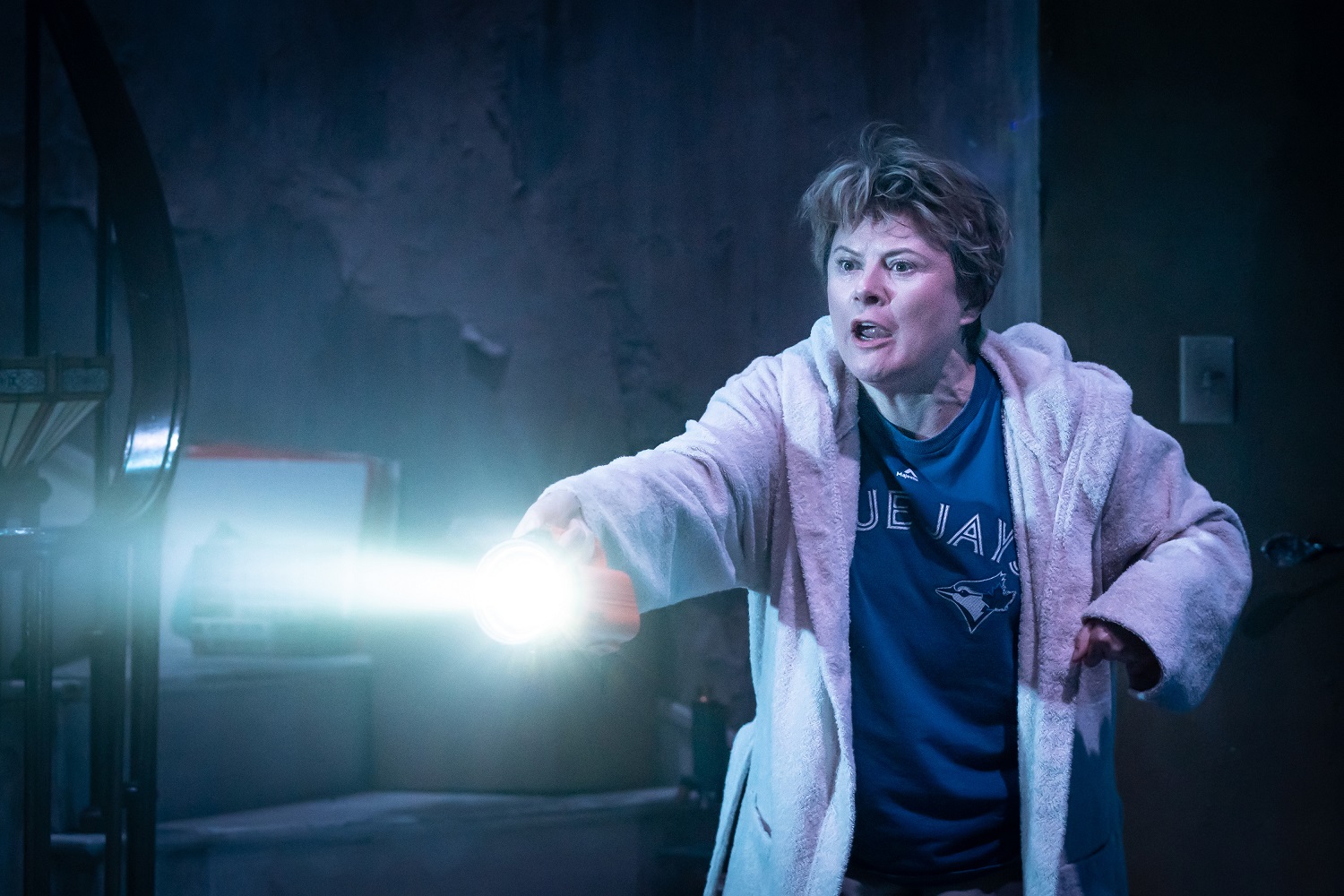

But if the form is hardly naturalistic, the protagonists of Appropriate are painfully raw in their emotional confrontations. For much of the time Monica Dolan (pictured above) moves between angry and positively furious as eldest child Toni, the daughter who paid most attention to her father after her siblings scattered, and still defends his memory; recently divorced, her relationship with her teen son Rhys (Charles Furness) is showing the strain. One brother, Bo (Steven Mackintosh), has long ago become a New Yorker, absorbing there a materialistic concern that makes him indecently eager to monetise family secrets; the other, Franz (Edward Hogg), has returned unexpectedly from a long absence during which he seems to have tamed past demons.

He has the recovering addict’s determination to apologise – it proves a rare moment of calm sincertty in an otherwise frenetic action – and he's helped along by his much younger fiancée River (Tafline Steen), who has a refreshing poise related to her being outside this toxic triad. Which is not something you can say of Bo’s wife, the brittle Rachel (Jaimi Barbakoff), who has absorbed all the family strife and added her own, her certainty about past anti-Semitic slights matched by her sarcasm. (Pictured below, from left: Edward Hogg, Steven Mackintosh, Jaimi Barbakoff)  The deceased patriarch must have been a complicated figure, his character split between the liberal Washington where he nearly became a Supreme Court judge, and the more ancient prejudices of the region to which he retreated (as well as the photographs, a startling final-scene reveal includes other familiar elements of that racist past). It certainly gives the three siblings enough to flay one another with, the slight consolation being that the generation of their children – Rhys is close to his younger cousin Cassidy (Isabella Pappas) – seems more emotionally mature. There’s a nice irony in Cassidy’s repeated assertion to her parents, as they try to keep things hidden from her, that she’s “almost an adult” – in many ways, she’s already more of one than any of them.

The deceased patriarch must have been a complicated figure, his character split between the liberal Washington where he nearly became a Supreme Court judge, and the more ancient prejudices of the region to which he retreated (as well as the photographs, a startling final-scene reveal includes other familiar elements of that racist past). It certainly gives the three siblings enough to flay one another with, the slight consolation being that the generation of their children – Rhys is close to his younger cousin Cassidy (Isabella Pappas) – seems more emotionally mature. There’s a nice irony in Cassidy’s repeated assertion to her parents, as they try to keep things hidden from her, that she’s “almost an adult” – in many ways, she’s already more of one than any of them.

The febrile brilliance of the writing is well served by Ola Ince’s tautly controlled direction, which modulates the stress flows of the piece, a balance that’s there in a set by Fly Davis that combines remnants of faded grandeur with the hoarder chaos that provides a memorable opening stage picture. Anna Watson’s lighting catches restrained interior hues, with a sense of outside brightness and heat slatted through closed shutters, while the sound design of Donato Wharton is almost a presence in itself, its insistent cicada humming nervously counterpointing the human action. Dip into Jacob-Jenkins’s elaborately poetic closing stage direction, in which he writes of the cicadas’ “long, enormously complicated, deeply layered, entirely improvised, ancient song”, and you may wonder whether his insects are wiser than his people. Superbly inventive theatre.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Add comment