'This goes beyond music and drama': tenor Nicky Spence on Martinů's 'The Greek Passion' | reviews, news & interviews

'This goes beyond music and drama': tenor Nicky Spence on Martinů's 'The Greek Passion'

'This goes beyond music and drama': tenor Nicky Spence on Martinů's 'The Greek Passion'

On his Christ-playing character in Opera North's new production of a Czech masterpiece

I’m a big fanboy of Czech music, Janáček and Martinů especially, but I’d never seen The Greek Passion before being cast as Manolios in Opera North’s new production, as it remains quite a rarity in the opera house. For those who don’t know the work, it tells of a group of refugees who arrive in a villa

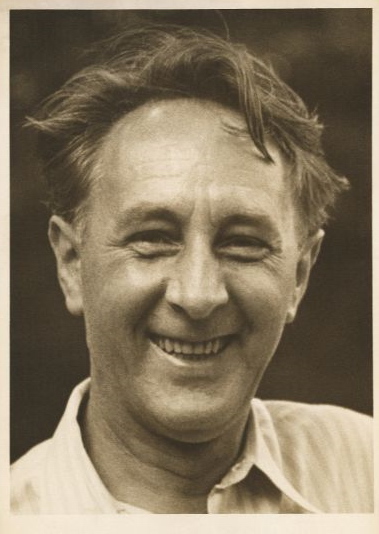

Martinů (pictured left in his American exile in 1943, a a decade and a half before he composed the opera) was displaced himself when he wrote the opera, having left his native Czechoslovakia some years before. The work was originally written for the Royal Opera House in the 1950s but, on receiving it, they decided it wasn’t intellectual enough for their audience. Martinů was devastated by this rejection and so he distributed pieces of his original score to various friends and acquaintances. He basically gave it all away. When he found out that Zurich Opera wanted to premiere it, instead of gathering it back together, he rewrote it in a more traditional grand opera style. At Opera North, we’re doing the first version which is more immediate and, to my mind, more appealing to a modern audience.

Martinů (pictured left in his American exile in 1943, a a decade and a half before he composed the opera) was displaced himself when he wrote the opera, having left his native Czechoslovakia some years before. The work was originally written for the Royal Opera House in the 1950s but, on receiving it, they decided it wasn’t intellectual enough for their audience. Martinů was devastated by this rejection and so he distributed pieces of his original score to various friends and acquaintances. He basically gave it all away. When he found out that Zurich Opera wanted to premiere it, instead of gathering it back together, he rewrote it in a more traditional grand opera style. At Opera North, we’re doing the first version which is more immediate and, to my mind, more appealing to a modern audience.

Musically when preparing to appear in an opera, you’re a joyous slave to the score until you’ve learned it by heart. The Greek Passion is interesting as it weaves spoken text with sung passages, Greek Orthodox chant sections together with folk strains, so it’s as much about the transitions between scenes as the music itself. Dramatically, I did as much preparation as I could beforehand so I could bring something to the rehearsal room, but it wasn’t until I met a refugee and asylum seeker personally through Opera North that I was able to flesh out my own thoughts, something which I found incredibly moving.

I think the way in which Christopher Alden, who’s directing the piece, is representing the refugees in the opera in a new way is incredibly effective. We often lump people together into palatable parcels when there is suffering on a universal scale, but their corresponding column inches rarely reflect the human story. In this production, the refugees are depicted as white effigies (pictured towards the end of the article) which are carried by the members of the Chorus of Opera North who give voice to both the villagers and the exiled. In this way, they entwine with society and we’ve done everything we can to humanise them; to let their individual plight speak with the correct weight it deserves.  In preparation for taking on the role, I also got hold of a copy of Christ Recrucified by Nikos Kazantzakis which was the book which inspired the opera. Reading it was a bit like having a user manual for the character itself. It’s filled with sensual details which helped add layers to my interpretation and fill out some of the plot which isn’t always addressed in the opera itself. Like the best composers, Martinů was gloriously economical in terms of what he decided to include in his self-penned libretto from the book’s text (which is rather epic at over 400 pages long in a tiny wee font). It’s interesting that this was encouraged by Kazantzakis in correspondence between himself and Martinů, and I certainly think it keeps the action vital for the audience.

In preparation for taking on the role, I also got hold of a copy of Christ Recrucified by Nikos Kazantzakis which was the book which inspired the opera. Reading it was a bit like having a user manual for the character itself. It’s filled with sensual details which helped add layers to my interpretation and fill out some of the plot which isn’t always addressed in the opera itself. Like the best composers, Martinů was gloriously economical in terms of what he decided to include in his self-penned libretto from the book’s text (which is rather epic at over 400 pages long in a tiny wee font). It’s interesting that this was encouraged by Kazantzakis in correspondence between himself and Martinů, and I certainly think it keeps the action vital for the audience.

My character, Manolios (Spence pictured above in rehearsal), is a young guy who is called to play the character of Jesus in the Passion Play. Before this, Manolios was disengaged and lost within his own past. He couldn’t find the words to express his unworthiness when confronted with playing the role of Christ. When the new group arrives in the village seeking refuge, Manolios is given the opportunity to put his head above the parapet and, through giving voice to them, finds something new in himself. He discovers a strength and beauty in his own imperfection and leads a provocation for our society to ‘give of yourself what you have too much of.’ It says to us all: do something, make a difference, the opportunity lives in all of us to change what’s happening.

My character, Manolios (Spence pictured above in rehearsal), is a young guy who is called to play the character of Jesus in the Passion Play. Before this, Manolios was disengaged and lost within his own past. He couldn’t find the words to express his unworthiness when confronted with playing the role of Christ. When the new group arrives in the village seeking refuge, Manolios is given the opportunity to put his head above the parapet and, through giving voice to them, finds something new in himself. He discovers a strength and beauty in his own imperfection and leads a provocation for our society to ‘give of yourself what you have too much of.’ It says to us all: do something, make a difference, the opportunity lives in all of us to change what’s happening.

It’s quite rare that you embark upon a piece which resonates so far beyond the opera house, but this goes beyond music and drama. The subject matter of how we treat people who have no choice but to be brave in seeking refuge in a new home isn’t a new one, but our ignorance and general apathy is as rank and fresh as it’s ever been – and feels particularly parlous when the issue of immigration dictates so many political decisions around the world. I personally felt highly embarrassed about how little I knew about the treatment of asylum seekers in this country and really hope that the important messages in The Greek Passion will provoke us to press re-set on today’s empty and uneducated rhetoric.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment