Ravens: Spassky vs Fischer, Hampstead Theatre review - it's game over for this chess play | reviews, news & interviews

Ravens: Spassky vs. Fischer, Hampstead Theatre review - it's game over for this chess play

Ravens: Spassky vs. Fischer, Hampstead Theatre review - it's game over for this chess play

The Cold War 'Match of the Century' fails to translate into compelling drama

We’ve had Chess the musical; now, here’s Chess the play.

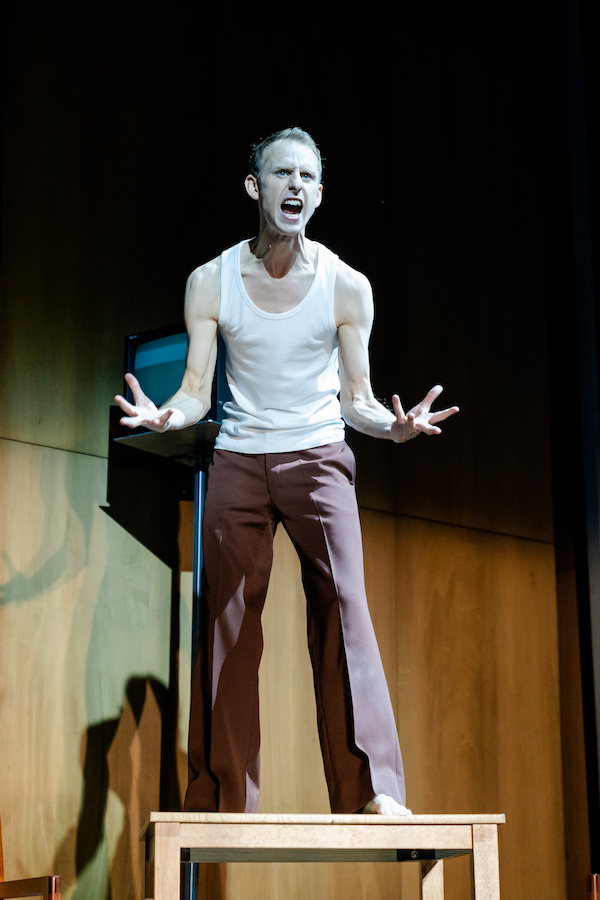

The play follows the tournament through, as both Fischer (Robert Emms, pictured below right) and Spassky (Ronan Raftery) spiral into paranoia, amplified by their various minders; at one point, there’s even talk of poisoning a dog. Meanwhile, the tournament organisers are more concerned with keeping the show on the road – and wondering whether catering to the whims of the diva-like American maverick, opening the floodgates for more like him, is really worth the trade-off of a TV broadcast, international publicity and renewed interest in the game since the brash Fischer gained celebrity status.

Morton-Smith has clearly done his research, and there are lots of fascinating ideas flying around here – some particularly timely, such as governments’ use of soft power, suspicions of cheating or foul play, how a charismatic individual can disrupt the system, and an attack on the very notion of objective truth. There’s also an interesting strand on how we indulge the bad behaviour of those we consider “geniuses”. However, running at an unwieldy near-three hours, this feels like material in search of a play. Crucially, it’s missing a streamlined, compelling dramatic arc, as well as the excitement and tension of a true thriller.

Morton-Smith has clearly done his research, and there are lots of fascinating ideas flying around here – some particularly timely, such as governments’ use of soft power, suspicions of cheating or foul play, how a charismatic individual can disrupt the system, and an attack on the very notion of objective truth. There’s also an interesting strand on how we indulge the bad behaviour of those we consider “geniuses”. However, running at an unwieldy near-three hours, this feels like material in search of a play. Crucially, it’s missing a streamlined, compelling dramatic arc, as well as the excitement and tension of a true thriller.

The title is perhaps misleading, since we spend far more time with the flamboyantly obnoxious Fischer than we do with Spassky. Emms gives a thoroughly committed performance as the former, particularly as Fischer unravels both physically and mentally, spewing antisemitic conspiracy theories (while denying his own Jewish heritage) and descending into a childlike state. However, a little of Fischer goes a very long way, and it begins to feel like we’re just repeating the same points: he’s terrified of losing, he needs to not just beat but destroy his opponents, he has a confused hatred of communism tied into his relationship with his mother, and – though he’s their boy wonder – he has no great love for America, or anyone else, since they all look down on him. It’s Fischer versus the world.

Ironically, Spassky, too, dislikes the nation he purportedly represents, but his position is perhaps the more interesting, and, as presented here, more nuanced. Being chess champion affords him the luxury of being apolitical in a feverishly political sphere, stepping outside Soviet strictures and into the escape of a comparatively clean, simple endeavour. Yet Fischer’s dubious gamesmanship – he turns up late to matches, demands a special chair, questions the chessboard – gets under Spassky’s skin, and his gradual loss of control is beautifully portrayed by Raftery. It’s just a shame that we only get to know Spassky in the second half, and that there’s little interaction between these two chess masters, who, despite their differences, understand one another on a profound level.

Part of the problem is that the chess matches themselves are confusing and undramatic. It’s unclear to the relative novice how the tournament and the scoring works, how Fischer and Spassky’s playing styles compare, and what we should be looking out for in their various encounters. Surely there are some theatrical devices that could be employed to open the game up to an audience? Or even something as simple as the use of commentary, since these matches were broadcast? What should be riveting duels are mainly incomprehensible.

Part of the problem is that the chess matches themselves are confusing and undramatic. It’s unclear to the relative novice how the tournament and the scoring works, how Fischer and Spassky’s playing styles compare, and what we should be looking out for in their various encounters. Surely there are some theatrical devices that could be employed to open the game up to an audience? Or even something as simple as the use of commentary, since these matches were broadcast? What should be riveting duels are mainly incomprehensible.

It’s also difficult to get a handle on the wider context, and how important this event was to those watching around the world. Other than brief use of video, we mainly spend time with people in suits standing around arguing in this one place – and the supporting characters lack definition. The exception is perhaps Soviet minder Nikolai Krogius, thanks to a commanding performance from Rebecca Scroggs (pictured above). There’s some much-needed levity, too, from Gary Shelford’s Icelandic policeman.

Annabelle Comyn’s production is most engaging when the tale descends into farce – Jamie Vartan’s set collapsing in on itself as the poor tournament organisers are forced, by the crazed Soviet and American teams, to search light fixtures for sabotage devices and x-ray chairs to hunt radio transmitters. But a key phone call between Henry Kissinger and Fischer pre-tournament is too muffled to understand, and – other than one match with some inventive movement from Mike Ashcroft – the piece generally feels static and repetitive. There’s an awful lot of pontificating about metaphorical readings of chess, not enough demonstrating through drama, or allowing the audience to connect to the characters and reach our own conclusions. There’s almost certainly a pertinent play somewhere in here, but it’s yet to fully emerge.

- Ravens: Spassky vs. Fischer is at Hampstead Theatre until 18 January

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Add comment