In photographer Jim Marshall’s heyday in the 60s and 70s, before the music business became corporate and restrictive, and before Marshall unravelled – he was partial to cars, cocaine and guns as well as cameras – musicians asked for him, they trusted him, and he never violated their trust because, he said, “these people have let you into their life”. The pictures he took of the Beatles, Janis Joplin (pictured below), John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Duane Allman, Joni Mitchell and countless others are startlingly intimate, as if, one of his friends observes, there is no one else in the room.

Alfred George Bailey’s absorbing documentary leaps back and forth between decades, often confusingly, with talking heads that include his assistant and archivist Amelia Davis – she is also a producer on the film and author of a book of the same name – as well as Anton Corbijn, Michael Zagaris, Metrropolitan Museum photography curator Jeff Rosenheim and Graham Nash.

An ex-girlfriend, Michelle Margetts, says he looked like a malevolent gnome when they met in 1984, though as she reads aloud an unpublished article she wrote about him she dissolves into tears (Marshall died in 2010 at the age of 74). “There was a hole in him that was unfillable,” she says. But their relationship remains impenetrable and hazy.

Marshall himself never quite comes into focus, though Davis conveys some of his contradictions. His friend Michael Douglas, whom he photographed on set on The Streets of San Francisco (Marshall was a native of the city) describes a guy with a big schnozz, who was always trying to get you to relax, but who was the “most uptight, strung-out guy you’ve ever seen” with his fingers “chewed down to the bone”. Maybe this endeared him to strung-out stars.

Marshall himself never quite comes into focus, though Davis conveys some of his contradictions. His friend Michael Douglas, whom he photographed on set on The Streets of San Francisco (Marshall was a native of the city) describes a guy with a big schnozz, who was always trying to get you to relax, but who was the “most uptight, strung-out guy you’ve ever seen” with his fingers “chewed down to the bone”. Maybe this endeared him to strung-out stars.

As Corbijn says, “However good you are, unless you have the access you don’t have the picture”, and Marshall certainly had access and a genuine, deep connection with his subjects. For Corbijn, his picture of Bob Dylan rolling a tire along a Greenwich Village sidewalk in 1963 is “close to perfection” and you can only agree.

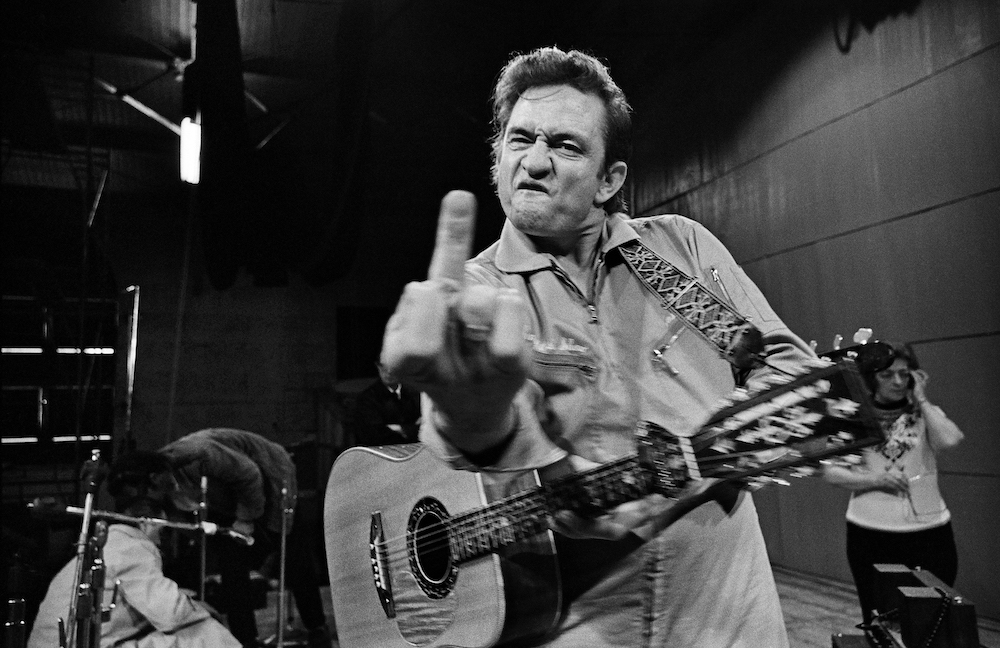

He was a soul mate of Johnny Cash (that says quite a lot), who asked him to document the concerts at Fulsom prison in 1968, and then a year later at San Quentin. Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, says he’s glad that there’s no video of Fulsom because Marshall’s photographs capture it better than any other format could. Especially that iconic one of Cash flipping the bird (below). “After the sound check I said, ‘Johnny, let’s do a shot for the warden’”, says Marshall, who was on probation himself at the time. He could be a nightmare, “the biggest asshole and then the sweetest guy in the world”, says Amelia Davis. She reckons the cocaine habit was his downfall. She quit her job twice, tired of the benders when he’d lock himself in his studio “to avoid hurting people”, but she always came back to clear up the mess, which was often bloody. “It comforted him to know that someone loved him enough to stay.” His wives weren’t so tolerant. He nailed his second one, a banker, in a closet – she left soon after, plunging him into more self-destruction. Dennis Hopper, it’s said, modelled his crazed photojournalist character in Apocalypse Now on Marshall.

He could be a nightmare, “the biggest asshole and then the sweetest guy in the world”, says Amelia Davis. She reckons the cocaine habit was his downfall. She quit her job twice, tired of the benders when he’d lock himself in his studio “to avoid hurting people”, but she always came back to clear up the mess, which was often bloody. “It comforted him to know that someone loved him enough to stay.” His wives weren’t so tolerant. He nailed his second one, a banker, in a closet – she left soon after, plunging him into more self-destruction. Dennis Hopper, it’s said, modelled his crazed photojournalist character in Apocalypse Now on Marshall.

He was convicted of attempted murder after shooting a friend of his first wife in 1968 – he got a fine and a suspended sentence – and in 1983 cops busted his San Francisco apartment and found a small arsenal, though he managed to do work furlough rather than jail time, luckily, as “he would have annoyed everyone in jail”. When he was on tour with the Stones in 1972 for Life magazine, he says he was taking more cocaine than they were.

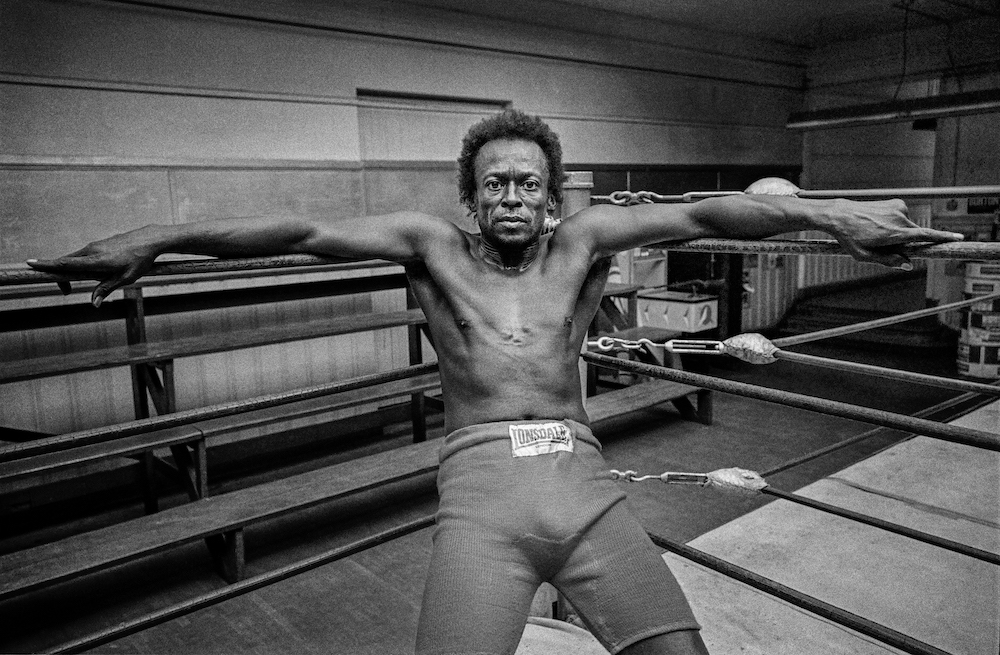

For years, he was in all the right places at the right time. In 1965 he was part of the “core Haight family”, taking pictures of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane before they were famous, and later Cream, the Who and Jimi Hendrix at the Fillmore. He was the photographer the Beatles requested for the last show they ever did, in Candlestick Park in San Francisco in 1966. And as well as taking wonderful portraits of jazz and rock stars (Miles Davis, pictured above) and music festivals, he also documented New York City street scenes, the civil rights movement and coalminers in Kentucky for a series on poverty in America.

For years, he was in all the right places at the right time. In 1965 he was part of the “core Haight family”, taking pictures of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane before they were famous, and later Cream, the Who and Jimi Hendrix at the Fillmore. He was the photographer the Beatles requested for the last show they ever did, in Candlestick Park in San Francisco in 1966. And as well as taking wonderful portraits of jazz and rock stars (Miles Davis, pictured above) and music festivals, he also documented New York City street scenes, the civil rights movement and coalminers in Kentucky for a series on poverty in America.

But in the mid-Eighties, people stopped calling. He and his gun habit weren’t welcome backstage. Later, when Davis threatened to leave for good if he didn’t sober up, he took her at her word and got clean. “I’ve been my own worst enemy,” he said. Cannily, he owned the copyright of everything he shot so he could live off his back catalogue when times got rough. And what a back catalogue it is. We may not like Marshall’s persona much, but in the end, the pictures tell the story.

Add comment