Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, Barbican review – a must-see exhibition | reviews, news & interviews

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, Barbican review – a must-see exhibition

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, Barbican review – a must-see exhibition

The masculine identity seen under the microscope

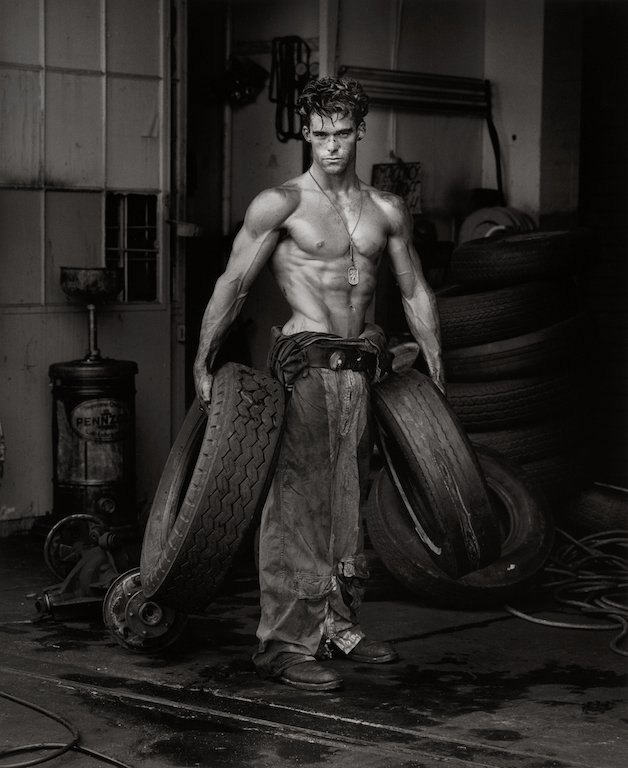

The exhibition starts on the Barbican’s lift doors, which are emblazoned with photographs from the show. They include one of my all-time favourites: Herb Ritts’s Fred with Tyres 1984 (pictured below right), a fashion shoot of a young body builder posing as a garage mechanic, in greasy overalls. Despite his powerful muscles, he looks tired and petulant.

Introducing the show is a quote from writer James Baldwin summing up the limitations of the simplistic role models held up as the norm in America and copied in so many countries. “The American ideal of masculinity,’ he writes, “has created cowboys and Indians, good guys and bad guys, punks and studs, tough guys and softies, butch and faggot, black and white. It’s an ideal so paralytically infantile that it is virtually forbidden – as an unpatriotic act – that the American boy evolve into the complexity of manhood.” Manhood is examined from every viewpoint in this visual feast of a show and I spent over three hours revelling in these wondrous complexities.

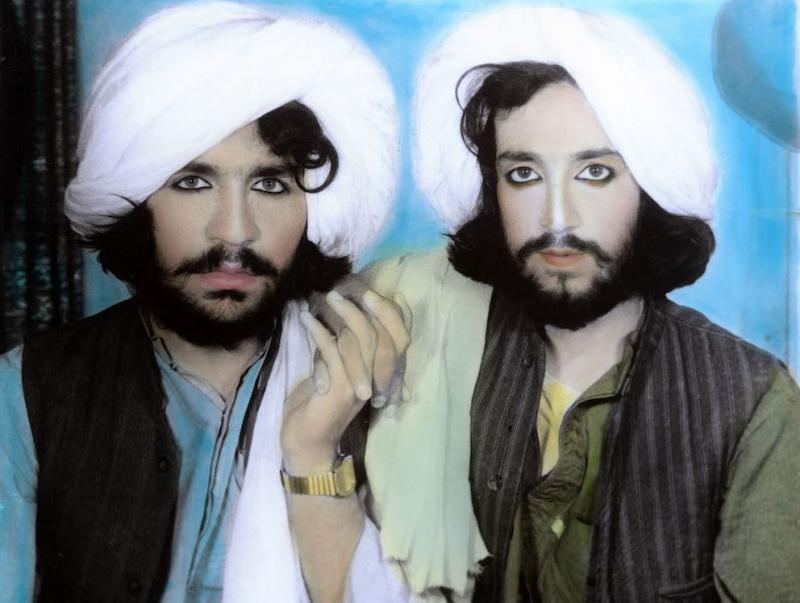

The show is divided into sections and under the rubric Disrupting the Archetypes, tough guys reveal their soft side. The Taliban may be portrayed in the West as ruthless fanatics, but here they are, eyes rimmed with kohl, holding hands like young lovers (main picture) or posing with bouquets of flowers before colourful backdrops. These astonishing shots were discovered in 2002, in a photography studio in Kandahar, by Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak, when on assignment in Afghanistan.

Snoozing Israeli soldiers also look as innocent as the day in Adi Nes’s 1999 photograph. In her photos of American High School footballers, Catherine Opie reveals the young lads hidden under huge shoulder pads that make them look like the incredible hulk. Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits of bull fighters fresh from the ring show them dishevelled, bloodied, traumatised and extremely relieved to be alive.

Snoozing Israeli soldiers also look as innocent as the day in Adi Nes’s 1999 photograph. In her photos of American High School footballers, Catherine Opie reveals the young lads hidden under huge shoulder pads that make them look like the incredible hulk. Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits of bull fighters fresh from the ring show them dishevelled, bloodied, traumatised and extremely relieved to be alive.

Overturning the mantra that grown men don’t cry, Dutch artist Bas Jan Ader sobs inconsolably in his video I’m Too Sad to Tell You, 1971 while in Pissing, 1995 Knut Asdam focuses on the stain spreading across a crotch as a grown man wets his pants. Jeremy Deller has created a shrine to Welsh wrestler Adrian Street, “King Kong in lipstick”. So Many Ways to Hurt Yourself, 2010 charts the rise of the flamboyant World Champion who was drawn to wrestling as much for the cross dressing as the fight. “I’m as tough as Marciano and as sexy as Mae West,” he chants and attributes his desperate need for attention to his father, “a bible bashing, bigoted bully, who never said a kind word to me, the hateful bastard.”

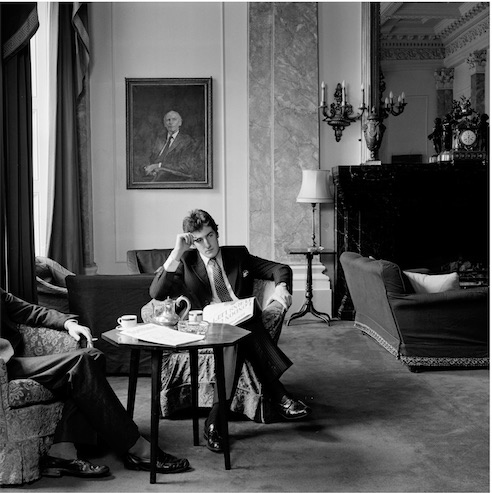

Other authoritarian bullies are herded into a section titled Male Order. Karen Knorr uses quotes to elucidate the nauseating mindset of entitlement she uncovers in members of gentleman’s clubs. “Newspapers are no longer ironed, coins no longer boiled; so far have standards fallen,” complains one disgruntled sitter. (pictured below left: detail of Newspapers are no longer ironed… from Gentlemen, 1981-3 by Karen Knorr). For what he describes as “a performance of masculinity and elite white male rage”, Richard Mosse invited members of the Yale Fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon to yell at full volume to camera for as long as possible. The winner, a no-neck bruiser, got a keg of beer for his efforts. Polish artist, Piotr Ulanski fills a whole wall with head shots of film actors playing Nazis to point up Hollywood’s ongoing love affair with fascists and bullies.

Family and Fatherhood is the most troubling section; both seem to be vexed issues. Richard Billingham’s photos of his alcoholic father, Ray, elucidate his abject failure as a parent; and by inserting himself into family photographs in place of the missing father, Dutch artist Hans Eijkelboon highlights a more common form of absence. Anna Fox’s little pink book My Mother’s Cupboards 1999 makes your heart bleed for brow-beaten housewives. Pictures of her mother’s neat closets suggest a life of dreary constraint, especially when juxtaposed with her husband’s insults. “She should be fried in hot oil” and "Beastly bitches, filthy cows” (vis a vis his wife and daughter) are written opposite the pictures in elegant copperplate, like poems in greeting cards. This exquisitely understated piece ticks in the brain like a time bomb waiting to explode into murderous rage.

Family and Fatherhood is the most troubling section; both seem to be vexed issues. Richard Billingham’s photos of his alcoholic father, Ray, elucidate his abject failure as a parent; and by inserting himself into family photographs in place of the missing father, Dutch artist Hans Eijkelboon highlights a more common form of absence. Anna Fox’s little pink book My Mother’s Cupboards 1999 makes your heart bleed for brow-beaten housewives. Pictures of her mother’s neat closets suggest a life of dreary constraint, especially when juxtaposed with her husband’s insults. “She should be fried in hot oil” and "Beastly bitches, filthy cows” (vis a vis his wife and daughter) are written opposite the pictures in elegant copperplate, like poems in greeting cards. This exquisitely understated piece ticks in the brain like a time bomb waiting to explode into murderous rage.

Queering Masculinity features Nigerian artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s delicious shots of black bodies, which range from the surreal to the fetishistic. A striding man brandishes a huge pair of tailor’s sheers at crotch level like a castrating demon, while in Untitled 1985 (pictured below right) a crouching man sends out mixed messages with his wild Afro hair and vulnerable posture.

I’ve never managed to catch Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston, although it was filmed back in 1989. His black and white tribute to the Harlem poet Langston Hughes is a lyrical fusion of fact and fiction overlaid with extracts from the poetry. Suavely beautiful black men sip champagne and smoke incessantly as they eye one another over in a smart night club.

I’ve never managed to catch Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston, although it was filmed back in 1989. His black and white tribute to the Harlem poet Langston Hughes is a lyrical fusion of fact and fiction overlaid with extracts from the poetry. Suavely beautiful black men sip champagne and smoke incessantly as they eye one another over in a smart night club.

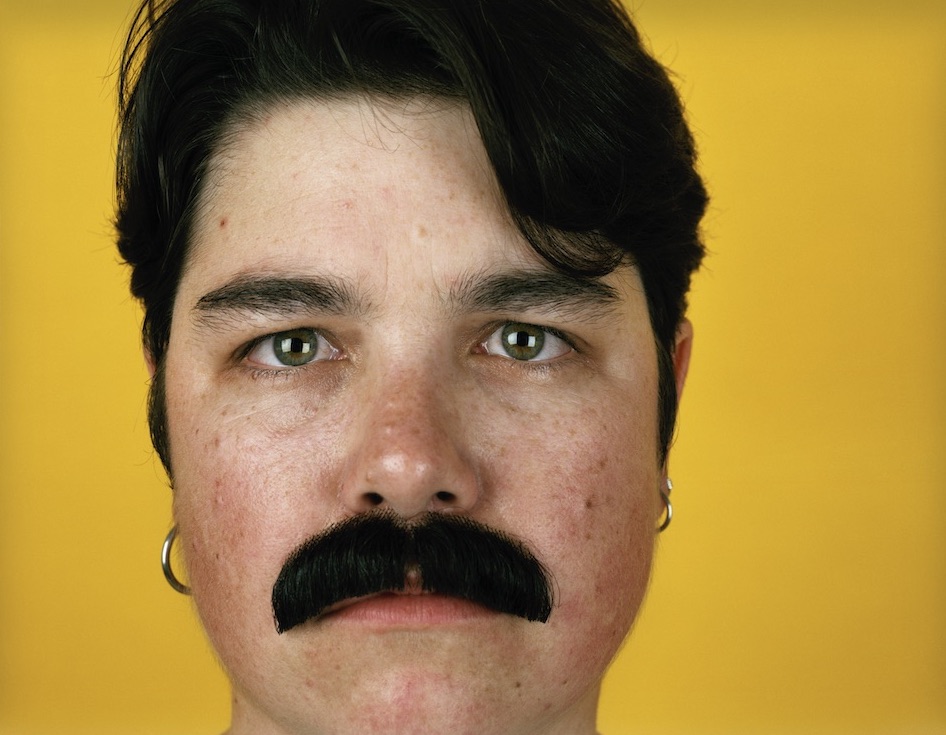

If the elegance of Julien’s characters seems effortless, in Being and Having 1991, Catherine Opie emphasises the degree to which masculinity is a performance. Donning a moustache, she becomes her male alter ego, Bo (pictured below). I found it impossible to gauge the gender of her companions, all of whom sport similarly flamboyant moustaches and go by deliberately ambiguous names like Whitey and Con. In her 1972 video, Ana Mendieta also uses facial hair to change her identity; as her friend snips off strands of his beard, she glues them onto her chin, until he is clean shaven and she has a full beard.

With works by women appearing throughout the show, the Women on Men section feels a tad sparse. In Heaven 1997 Tracey Moffatt films surfers in Australia stripping off their wetsuits. As she gets braver and goes in close, her targets become bashful, unsure how to respond to the intrusion. Laurie Anderson reversed the usual roles more emphatically by photographing men who propositioned her on the streets of Manhattan. Unnerved by this change in the rules, the predators become coyly apologetic. To protect their identities and also to further deny them the gaze, Anderson blanks out her subject’s eyes with white strips.

Many of the images on show are familiar and most pre-date the millennium, yet they still feel relevant and timely. Instead of feeing shocking or confrontational, much of the work has mellowed into an affectionate appraisal of traditional stereotypes. The way men behave impacts on both sexes, so it’s in all our interests to loosen the grip of harmful role models and open the way for more humane identities to emerge. In the meantime, don’t miss this wonderful show; it may just change your life.

Many of the images on show are familiar and most pre-date the millennium, yet they still feel relevant and timely. Instead of feeing shocking or confrontational, much of the work has mellowed into an affectionate appraisal of traditional stereotypes. The way men behave impacts on both sexes, so it’s in all our interests to loosen the grip of harmful role models and open the way for more humane identities to emerge. In the meantime, don’t miss this wonderful show; it may just change your life.

- Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at the Barbican until 17 May

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment