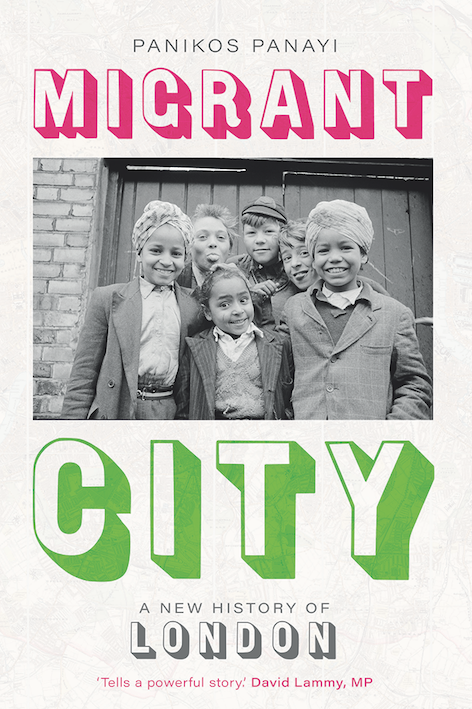

Panikos Panayi: Migrant City review – the capital of the world | reviews, news & interviews

Panikos Panayi: Migrant City review – the capital of the world

Panikos Panayi: Migrant City review – the capital of the world

A sprawling, sweeping history of London as an immigrant metropolis

Some menus never change. In 1910, the Loyal British Waiters Society came into being, prompted by “xenophobic resentment at the dominance of foreigners in the restaurant trade”. London’s German Waiters Club, one symptom of the alien rot the bulldog servers aimed to stop, was itself founded in 1869.

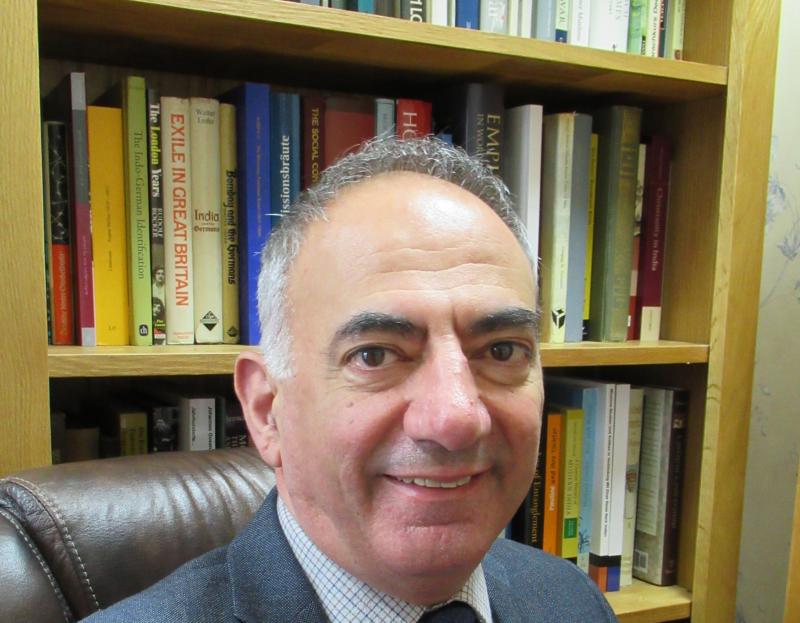

Britain’s all-powerful metropolis hardly wants for erudite, eloquent chroniclers. It remains “the capital of everything”, historical writing included. Organised according to theme and sector rather than chronology, Panayi’s account of the city as a global “magnet” for everyone from cleaners to oligarchs does not compete with broad-brush narrative histories from the likes of Peter Ackroyd, Stephen Inwood, Dan Cruickshank, or the great Jerry White. With his chief focus on the 19th and 20th centuries, and briefer excursions back as far as Roman times, Panayi excels at economic history, patterns of settlement, and the long-term evolution of migrant communities from Huguenots and Jews to Poles and Bangladeshis. He switches his attention between century-crossing trends (the millennium-old record of both Irish and Jewish immigration to London, for example) and the close-focus detail that packs Migrant City with glinting nuggets on almost every page. Did you know, for example, that Greek Cypriot settlement routes in London followed the stops on the 29 bus route? That particular community is Professor Panayi’s own. In occasional flashes, he opens the door on the historian’s own life, from the already-embedded multiculturalism of his primary school in 1960s Hornsey (“a lack of diversity makes me feel uncomfortable”) to his pastry cook father’s progress, within a decade, from East End bedsit to four-bedroom house in Crouch End.

London’s labour market, and its role as in recruiting and sorting migrant groups, lends this history its special forte. From the “cheap labour” of navvies, maids and sailors to the international bankers and entrepreneurs who have moved to the capital ever since the 18th century, migration to London has tracked the city’s changing but consistent role as a European, imperial and global entrepôt. Over the centuries, migrants have experienced both upward and downward mobility as “the London economy eats up and spits out people on all parts of the social scale”. Panayi’s hard-headed grasp of “the working life of the world’s capital” grounds his book in the struggle for survival – and the aspirations to prosperity – that migrants and their offspring have always shared with their fellow-citizens. From Jewish rag-trade workers in the East End and the West Indians recruited by the postwar transport system (in 1956, London Transport went shopping for them in Barbados) to Irish building labourers and the Bangladeshi grip on “Indian” restaurants, he throws new light on the “ethnic clustering” that has drawn migrant communities to specific crafts, trades and businesses. At every class level, from Jewish tailors to Sikh food preparers, Greek ship owners to German bankers, not only do strong networks based on kinship and origin knit the pieces in London’s migrant patchwork together. They may endure over many generations. Known and trusted routes take people to London, to particular suburbs and districts, then into occupations that may evolve into family or ethnic standbys. This process explains absences as much as presences: the dearth of Asian (as opposed to Caribbean- or African-origin) professional footballers, for example, may owe a lot to “the role of networks and career paths which appear to last for decades or even centuries”.

Panayi tells well-known stories of “ethnic clustering” but also lays stress on less familiar trades: the long-standing concentration of London Germans in baking and other food businesses, for example. By 1913, 40 out of 138 stores on Charlotte Street had German names over the door; the “Austro-Bavarian Lager Beer Company” began brewing in 1880s Tottenham. And, in the vicious anti-German pogroms of the First World War, the numerous and seemingly well-assimilated Germans of London suffered one of the worst bouts of the foreigner-bashing rage that punctuate this history, from the “Evil May Day” riots of 1517 to the sporadic outbursts of today. Panayi writes, hopefully, that the large-scale violent racism of the 1930s or 1970s “appears consigned to the past”. But he insists that prejudice – public and private – recurs, and that “the capital has not moved from a situation of racist hell to multicultural paradise”. Collective hatred may always break out like “a type of thunderstorm”.

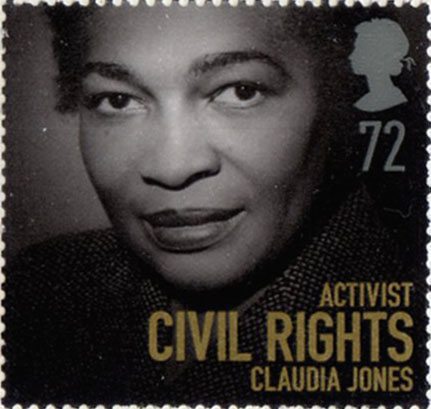

In the 21st century, “difference has become the norm” in this cosmopolitan metropolis. By 2011, almost three million of the capital’s fast-expanding 8.2 million population were born outside the UK. Panayi explains how this “superdiversity” happens but never makes a fetish of it. Rather, the lives of migrants and their children “run parallel” to their neighbours’ and, frequently, intersect or intertwine with them. He rightly questions the aptness of “ghetto” terminology to any London area, even Jewish Whitechapel or Caribbean Brixton in their heyday, and shows that the city-wide spread of migrant families has always balanced any hotspots of “ethnic concentration”. In any case, boundary-busting love and friendship, as much as racism and xenophobia, threads across his social panorama of a city where, by the 2011 census, 5 per cent of Londoners “described themselves as mixed race”. Maverick outsiders become pillars of mainstream culture: Claudia Jones, for example, a left-wing activist from Trinidad via Harlem (pictured above on a 2008 stamp), founded the Notting Hill Carnival. Migrant communities now have metropolitan roots as deep – no, deeper – than fish-and-chips, that novelty hatched in the Jewish East End of the Victorian age.

In the 21st century, “difference has become the norm” in this cosmopolitan metropolis. By 2011, almost three million of the capital’s fast-expanding 8.2 million population were born outside the UK. Panayi explains how this “superdiversity” happens but never makes a fetish of it. Rather, the lives of migrants and their children “run parallel” to their neighbours’ and, frequently, intersect or intertwine with them. He rightly questions the aptness of “ghetto” terminology to any London area, even Jewish Whitechapel or Caribbean Brixton in their heyday, and shows that the city-wide spread of migrant families has always balanced any hotspots of “ethnic concentration”. In any case, boundary-busting love and friendship, as much as racism and xenophobia, threads across his social panorama of a city where, by the 2011 census, 5 per cent of Londoners “described themselves as mixed race”. Maverick outsiders become pillars of mainstream culture: Claudia Jones, for example, a left-wing activist from Trinidad via Harlem (pictured above on a 2008 stamp), founded the Notting Hill Carnival. Migrant communities now have metropolitan roots as deep – no, deeper – than fish-and-chips, that novelty hatched in the Jewish East End of the Victorian age.

Sometimes, though, Panayi’s choice of figures and histories can seem arbitrary. Why cite Marc Bolan and Alma Cogan as examples of London Jewish pop stars but overlook the immortal Amy Winehouse? Although Migrant City offers an eye-opening chapter on religion (or its neglect) among migrant communities, it pretty much ignores literature, science and non-musical entertainment. Beyond a brief segment on the city as “a crucible for the development of international revolutionary ideas” among political exiles from Marx and Mazzini to jihadi preachers such as Abu Hamza, it has little to say on London as a global hub of thought, from Erasmus to Freud and beyond. Other writers have paid, and should pay, more attention to these themes. Migrant City shines above all as a sprawling treasure-house of immigrant trajectories framed by an unusually firm grasp of the capital’s economic realities. I expect to see novelists, journalists and TV researchers plunder it – with due credit, let’s hope – for years to come. With his sweeping perspective, Panayi reminds us that migrants can be rich, middling or poor: Harry Gordon Selfridge from Chicago earns his place as much as the Latin Americans who today may clean his eponymous store. And he traces the “gradual intergenerational process” of social mobility – perhaps best exemplified by London’s Jewish communities, en route from Stepney to Stanmore – with zest and heart as well as scholarship. An absurdly polarised property market, plus the current Brexit-era spasm of nativist politics, may mean that the immediate future of London migration does not exactly mirror its fluid past. Still, as this always-absorbing and often moving book explains, the ghosts of those Loyal Waiters will have to wait a lot longer before they see a full-English staff at Pret.

- Migrant City: a new history of London by Panikos Panayi (Yale University Press, £20)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment