Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse, Royal Academy, Exhibition on Screen/Facebook Premiere - a hardy perennial returns | reviews, news & interviews

Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse, Royal Academy, Exhibition on Screen/Facebook Premiere - a hardy perennial returns

Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse, Royal Academy, Exhibition on Screen/Facebook Premiere - a hardy perennial returns

Monet's garden at Giverny provides an escape back to a hit exhibition from 2016

Anyone lucky enough to have a garden will be newly appreciative of the oasis that even the humblest of outdoor spaces can provide. Based on the Royal Academy’s hugely successful 2016 exhibition of the same name, and broadcast on Monday evening by Exhibition on Screen via Facebook, Painting the Modern Garden opened the door to a different world.

Monet, the painter of water-lilies, might be the most famous of artist-gardeners, but he is one of many who found in his garden not just an ever-ready, ever-changing subject to return to again and again, but a place to experiment and to refresh body and mind. Their tranquility might seem at odds with the frenetic, urban preoccupations of the avant-garde, but gardens were a vital component in the modernist projects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

For Kandinsky, Matisse, and Nolde, gardens were living palettes, allowing them limitless scope to experiment with pure colour. The German impressionist Max Liebermann created a series of gardens, providing himself with a variety of subjects to paint, while Joaquín Sorolla’s Islamic-inspired gardens were popular with his American clientele. For Monet, painting and gardening were perhaps uniquely entwined, the head gardener at Giverny speaking with insight about the connection between the planting at Giverny and Monet’s canvases. Monet’s garden became, over time, a work of art in itself, the forerunner of Robert Smithson’s land art.

For Kandinsky, Matisse, and Nolde, gardens were living palettes, allowing them limitless scope to experiment with pure colour. The German impressionist Max Liebermann created a series of gardens, providing himself with a variety of subjects to paint, while Joaquín Sorolla’s Islamic-inspired gardens were popular with his American clientele. For Monet, painting and gardening were perhaps uniquely entwined, the head gardener at Giverny speaking with insight about the connection between the planting at Giverny and Monet’s canvases. Monet’s garden became, over time, a work of art in itself, the forerunner of Robert Smithson’s land art.

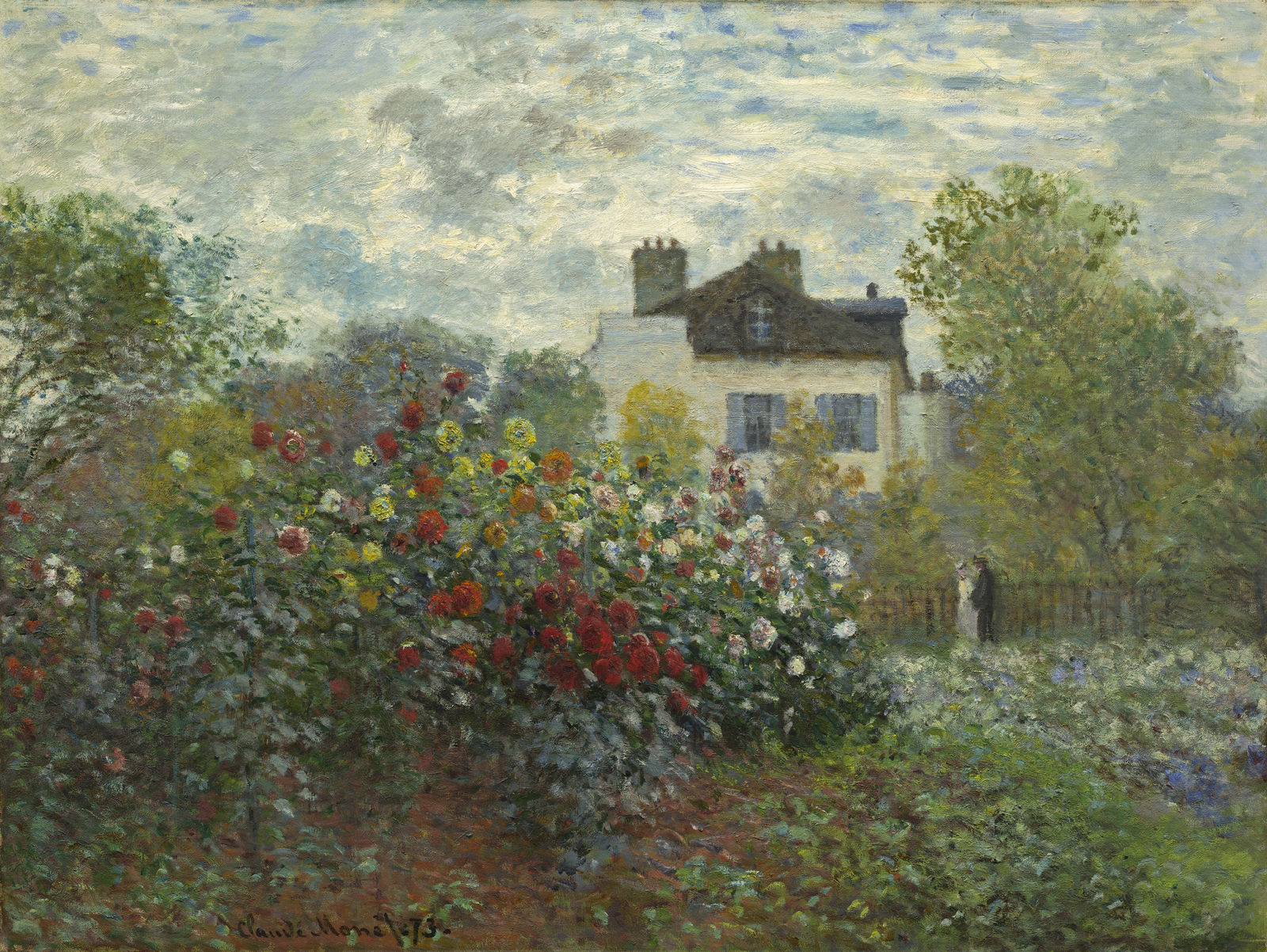

Gardening was a pastime that emerged with the middle-classes in the 19th century, against the backdrop of the new science of horticulture, and the discovery of exotic species across the globe. In the wake of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published to much controversy in 1859, Monet and Caillebotte’s shared trips to flower shows seem more subversive than quaint, the cultivation of plant varieties a conspicuous intervention in the natural world (pictured above: Monet, The Artist's Garden in Argenteuil, 1873).

Gardens have been depicted in painting since ancient times, accumulating symbolic resonances over the centuries as expressions of the Virgin Mary’s purity, or of pure power at Versailles in the 17th century. Munch didn’t just paint an apple tree, but each time explored afresh the Garden of Eden, and the Tree of Good and Evil.

Made within the sound of the western front, Monet’s immersive expanses of waterlilies generated new resonances, with the artist giving a vast panorama to the French state following the Armistice in 1918. Increasingly abstract, Monet located the universal in the smallest detail, finding within a ripple on the pond not just respite, but the painterly impulses that would blossom anew in the mid-20th century.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment