Caroline Maclean: Circles and Squares review - adventurous art, progressive living and a good gossip | reviews, news & interviews

Caroline Maclean: Circles and Squares review - adventurous art, progressive living and a good gossip

Caroline Maclean: Circles and Squares review - adventurous art, progressive living and a good gossip

Maclean's captivating narrative reveals the period when British art was at the vanguard

There was a moment in the 1930s when it seemed that contemporary art, as practised in Britain, might join the mainstream of the Western avant-garde.

Maclean’s entertaining book presents its serious subject in an easy colloquial style, inviting us into the adventurous art world in Britain (which was then so small that everyone knew everyone) as if into a good gossip. Artists from Henry Moore to Ben Nicholson, and Barbara Hepworth to Jack Pritchard, meet, seek to make their living, fall in love, wreak havoc, and throughout remain passionate about their art as well as one another.

As a tale of journeys both geographical and emotional, and relationships that withstood conflicting ideals and frequent rearrangements, the book is captivating and wide-reaching. It’s also a challenge to keep everything straight, despite the handy map: Isokon (also known as the Lawn Road Flats: an experiment in modernist small apartments), Ernö Goldfinger’s trio of houses in Willow Road, the Everyman cinema, the Mall Studios and Parkhill Road are all clearly noted, amongst other landmarks. While London is the fulcrum for Maclean’s book, she also tracks journeys within Britain (Cornwall, Yorkshire, Cumbria) as well as from the continent: emigrés from Walter Gropius (founder of the Bauhaus) to Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who escaped across the Channel as the political crisis deepened, amplifying contemporary debate and influencing artistic practice.

The captivating narrative begins with Ben Nicholson falling for the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, leaving his first wife, painter Winifred Nicholson. From there, Maclean focuses on the interplay between personal relationships and creative achievement: engineer Jack Pritchard and his wife Molly, for example, who completed the Isokon building with architect Wells Coates while maintaining a ménage à trois. From sculptor Henry Moore and his painter wife, Irina; to writer and editor Herbert Read married to musician "Ludo"; the giants Piet Mondrian (who loved London but felt he had to go to New York) and Alexander Calder, Maclean’s broad cast are all characters who managed, against all the odds, to be innovative, deeply committed artists striving for a new progressive form of living in a Britain that was basically conservative.

In complement to the shifting personal liaisons, the groups formed and reformed, as did the publications and the arguments. Various "isms" jostled against one another: surrealism, romanticism, constructivism. Nicholson, in particular, was concerned his colleagues’ art might be tinged with surrealism as opposed to pure abstraction. Debate raged; art really mattered.

Astonishingly, it was only in 1936 that the first exhibition purely centred on abstract art was organised. "Abstract & Concrete" was its title. It travelled to Liverpool, Oxford, Cambridge and the Lefevre Gallery in London, including a spectrum of artists from Wassily Kandinsky to Calder, and Gabo Miro to Alberto Giacometti, alongside their British peers. The same year, a mixed exhibition of applied and fine art included Constantin Brancusi, Moholy-Nagy, Hepworth, Moore, Nicholson and Giacometti, as well as furniture by Marcel Breuer and a radio by Wells Coates. Nothing was sold.

When war came, despite the War Artists Commission and other attempts to sustain British art, the period of innovation faded. Today, amid the screaming cacophony of the international art world, the British contribution is hardly dominant. Caroline Maclean’s enthusiastic, even breathless, canter through British art in the 1930s shows us where this country was once almost at the vanguard, with a momentum that dissipated understandably in the war years, and which has never quite been recaptured.

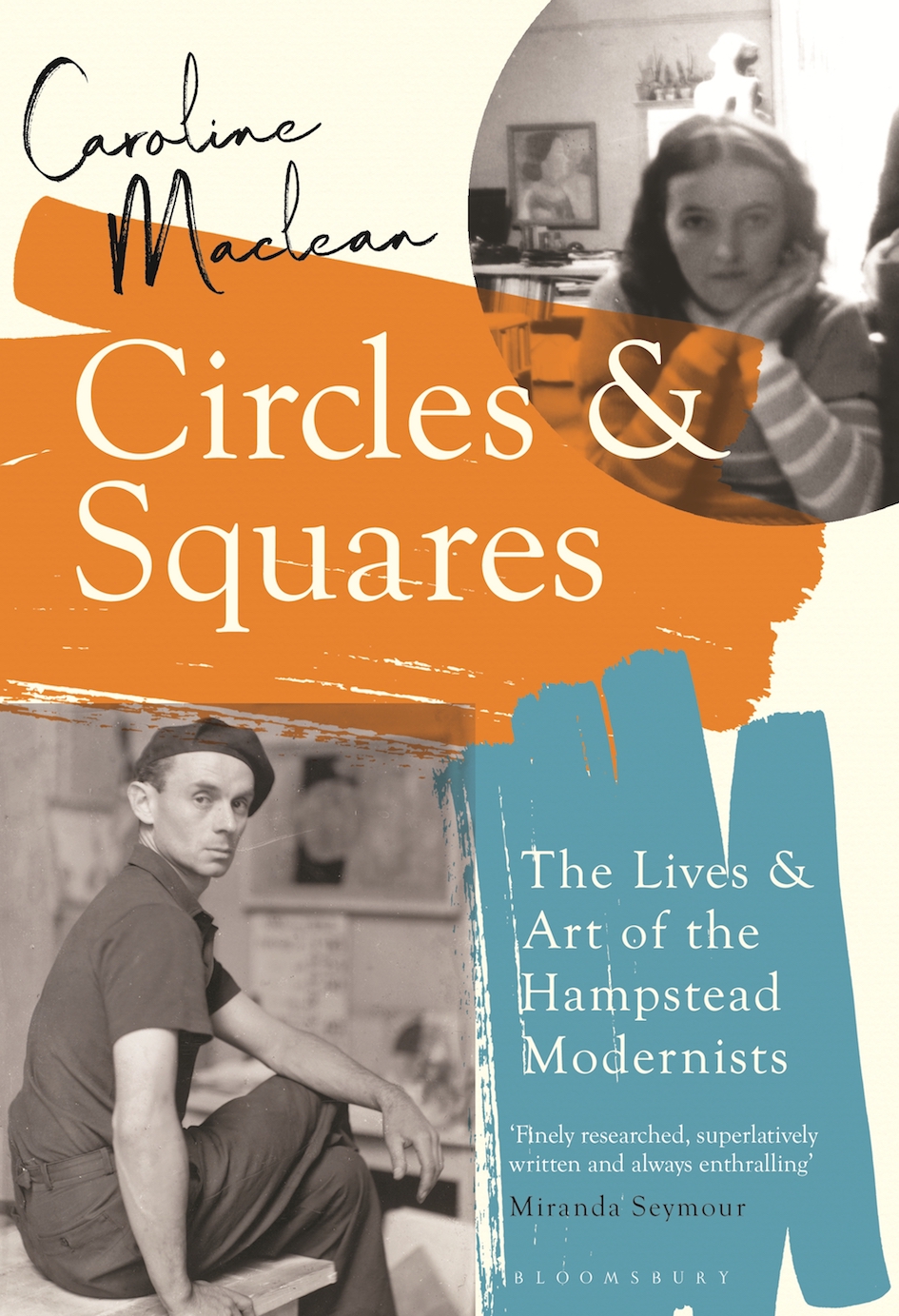

- Circles and Squares: The Lives and Art of the Hampstead Modernists by Caroline Maclean (Bloomsbury £30.00)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Add comment