Joseph Mazur: The Clock Mirage review – brief histories of time | reviews, news & interviews

Joseph Mazur: The Clock Mirage review – brief histories of time

Joseph Mazur: The Clock Mirage review – brief histories of time

How planets, people and proteins count the days and years

The Greek philosopher Zeno’s paradoxes, which have plagued thinkers for around 2500 years, tell us that super-speedy Achilles can never outrun the tortoise and that an arrow in flight must always occupy a fixed position at intervals of time – and so can never hit its target.

It would be otiose to say that Mazur – an emeritus professor of mathematics and prolific popular-science author – has taken on an impossible task in his “curious tour of time”. Of course he has, as the notion (in his words) “slips through every attempt to corral it”. It infuses almost every domain of human thought from microbiology to astrophysics, not to mention all the arts, and the history of philosophy throughout every ancient culture. Our elusive ideas of time, Mazur admits, stubbornly belong in “that realm of thought that blocks satisfaction”. But that’s no reason not to keep on trying to refine them for the rest of our allotted span – especially, perhaps, during this time-halting, time-bending pandemic that, for many people, made March drag by for a decade while May flashed past in a week.

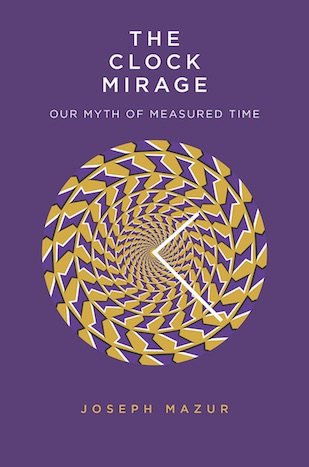

In spite of his glancing allusions to novels, movies and music, Mazur by and large keeps to the core scientific disciplines, which he expounds with practised fluency and frequent charm. The Clock Mirage begins with the mathematics that holds the time-bound cosmos together, and proceeds through physics, astronomy (and cosmology) as they develop through millennia and across the observed universe. It tracks the evolving technologies of human-measured time, then withdraws back into the human body and its own complex internal clocks. Along the way, Mazur takes time out to introduce snippets of interviews and anecdotes that highlight the different kinds of time experienced by truckers, astronauts, prisoners and sportspeople, among others. These episodes divert and sometimes move – as when we hear of the incalculable tedium of the iPhone assembler in China, or the jailed lifer’s “severe agony of timelessness” in solitary confinement – but don’t always mesh closely with the main arguments.

Within a mere 230 pages of text, this all makes for a feature-packed, multi-dial super-watch of a book. It bristles with intellectual widgets cunningly squeezed into a machine of modest size. Mazur does the heavy lifting of scientific synopsis and explanation with polished assurance, but sometimes the reader does yearn to slow down and take a breather. Meanwhile, his more reflective passages have a quirky idiosyncrasy that can delight but baffle (“We also know that when we scramble an egg, we have moved the existence of that egg to whatever it has become in time”). Yes, his topic calls for the poet’s as well as the physicist’s eye, but in that case why not yield more space to the real pros – such as TS Eliot’s time-obsessed Four Quartets, or the Modernist artworks from Proust to Dali (pictured below: ‘The Persistence of Memory’, 1931; MoMA, New York) that have creatively warped and fractured time?

Still, for all the breadth of Mazur's canvas and the intricacy of its detail, he does keep his narrative ticking along at a steady and engaging beat. Zeno’s antique posers recur through the ages: pure thought, science and technology tease out the relationship between time, space, motion, and the human consciousness that seeks to combine all into a plausible whole. For the mind, and maybe for the universe, time remains forever “both continuous and discrete”. It is divisible into concrete units and measures, yet felt and observed as an uninterrupted flow, river or stream. The perennial gap between the “subjective perceptual” and “objective conceptual” notion of time, and human attempts to bridge it, lends The Clock Mirage the regular rhythm of a swinging pendulum. From the first astronauts to visit the Moon to experimental dwellers in a darkened cave, the book fills with examples of the disparity between the “scaled measure” of time mandated by scientists, horologists and bureaucrats, and the mind’s own plastic “sense of duration”. The latter shrinks, bends or magnifies moments or years as experienced in boredom, excitement, fear or sickness.

Still, for all the breadth of Mazur's canvas and the intricacy of its detail, he does keep his narrative ticking along at a steady and engaging beat. Zeno’s antique posers recur through the ages: pure thought, science and technology tease out the relationship between time, space, motion, and the human consciousness that seeks to combine all into a plausible whole. For the mind, and maybe for the universe, time remains forever “both continuous and discrete”. It is divisible into concrete units and measures, yet felt and observed as an uninterrupted flow, river or stream. The perennial gap between the “subjective perceptual” and “objective conceptual” notion of time, and human attempts to bridge it, lends The Clock Mirage the regular rhythm of a swinging pendulum. From the first astronauts to visit the Moon to experimental dwellers in a darkened cave, the book fills with examples of the disparity between the “scaled measure” of time mandated by scientists, horologists and bureaucrats, and the mind’s own plastic “sense of duration”. The latter shrinks, bends or magnifies moments or years as experienced in boredom, excitement, fear or sickness.

“We are all living in different time worlds,” Mazur notes. Yet, from the Babylonian sundial to the caesium atomic clock that will be “off by just short of a second every twenty million years”, human communities have grown up around shared fictions of a uniform perception of its passing. Just as industrial societies demanded ever-more accurate timepieces to ensure that “Time was in control of everything one did”, so Newtonian physics created the cosmos in the image of “some intangible clock that beats out the pulse of the universe”. Mazur shows, as many writers have before, how this mechanistic “absolute time” broke down into the relativistic space-time of Einstein and his contemporaries.

Our bookshelves hardly lack for affable beginner’s guides to relativity. Mazur, however, writes as a veteran teacher who knows how deeply this “crazy… messing of the mind” can disrupt our everyday sense of reality. However blasé, we will struggle to grasp how an astronaut on the International Space Station, Scott Kelly, could return to earth 8.6 milliseconds younger than his earthbound twin brother, Mark. And, if Mazur’s discussion of the possibilities of time-travel and its practical limitations has a certain sense of déjà vu for any pop-science or SF buff, it’s always good to be reminded why you shouldn’t go back and take out young Hitler (even if you theoretically can…)

As he pivots between subjective and objective time, two sets of data help Mazur cross the gulf between the “imaginary” time in our heads and the arbitrary calibrations that make human communities tick. First, of course, comes the earth’s daily cycle of rotation on its axis, as divided by Egyptian and later cultures into hours, minutes and finally seconds, and its yearly revolution around the sun. How, though, does this non-human astronomical time – which societies and eras have carved up in many different ways – take root in our embodied sense of duration? The most distinctive, and revealing, aspects of The Clock Mirage appear in Mazur’s discussion of recent research into body-clocks, circadian rhythms, and the evolutionary attunement between our physical being and the cycles of days and seasons. Miss a few nights’ sleep, work an irregular night-shift, or just take a long-haul flight (if we ever can again), and learn about the objective reality of circadian systems the hard way. “Like trains, our bodies run on a timetable.” From jet-lag to the sickness that sleep disruption brings, our internal clocks, controlled by a “master pacemaker” in the brain’s hypothalamus, prove every day that time is not merely “a fabrication built in my head”. Yet organic causes also lie behind its perceived elasticity. Mazur explores the reasons why the ageing brain feels the years to be speeding up, while threat and terror slow our seconds down in “a temporal illusion that benefits survival”.

As he pivots between subjective and objective time, two sets of data help Mazur cross the gulf between the “imaginary” time in our heads and the arbitrary calibrations that make human communities tick. First, of course, comes the earth’s daily cycle of rotation on its axis, as divided by Egyptian and later cultures into hours, minutes and finally seconds, and its yearly revolution around the sun. How, though, does this non-human astronomical time – which societies and eras have carved up in many different ways – take root in our embodied sense of duration? The most distinctive, and revealing, aspects of The Clock Mirage appear in Mazur’s discussion of recent research into body-clocks, circadian rhythms, and the evolutionary attunement between our physical being and the cycles of days and seasons. Miss a few nights’ sleep, work an irregular night-shift, or just take a long-haul flight (if we ever can again), and learn about the objective reality of circadian systems the hard way. “Like trains, our bodies run on a timetable.” From jet-lag to the sickness that sleep disruption brings, our internal clocks, controlled by a “master pacemaker” in the brain’s hypothalamus, prove every day that time is not merely “a fabrication built in my head”. Yet organic causes also lie behind its perceived elasticity. Mazur explores the reasons why the ageing brain feels the years to be speeding up, while threat and terror slow our seconds down in “a temporal illusion that benefits survival”.

Time, at the close of Mazur’s brief history, sports a double clock-face. One consists of a necessary fiction, rewound from age to age – an imaginary “planner of our presence in the world”, from the water-cloaks of Ancient Greece to today’s Google alerts. The other dwells deep in our cells, as biochemical markers toil to keep corporeal time through each alternation of light and dark, all devoted to “the necessity of keeping us alive”. Mazur doesn’t pretend to find a final synthesis, but he does show why these various versions of temporality offer “a dialectic with no obvious resolution”. Readers will learn plenty from The Clock Mirage, be stretched by it, and have fun en route. It passes the time enjoyably and productively. Even if, as Beckett’s Estragon bleakly retorts in Waiting for Godot, “It would have passed in any case”. “Yes,” Vladimir replies, “but not so rapidly.” Precisely so.

- The Clock Mirage: Our Myth of Measured Time by Joseph Mazur (Yale University Press, £20)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment