Proxima review - family frays before lift-off | reviews, news & interviews

Proxima review - family frays before lift-off

Proxima review - family frays before lift-off

Eva Green reaches for the stars while raising a daughter in a sober space movie

This sober French space movie is concerned with what a female astronaut leaves behind on Earth, not what she finds in the cosmic dark. Sarah (Eva Green) has been selected for a European Space Agency mission towards Mars, realising a childhood dream.

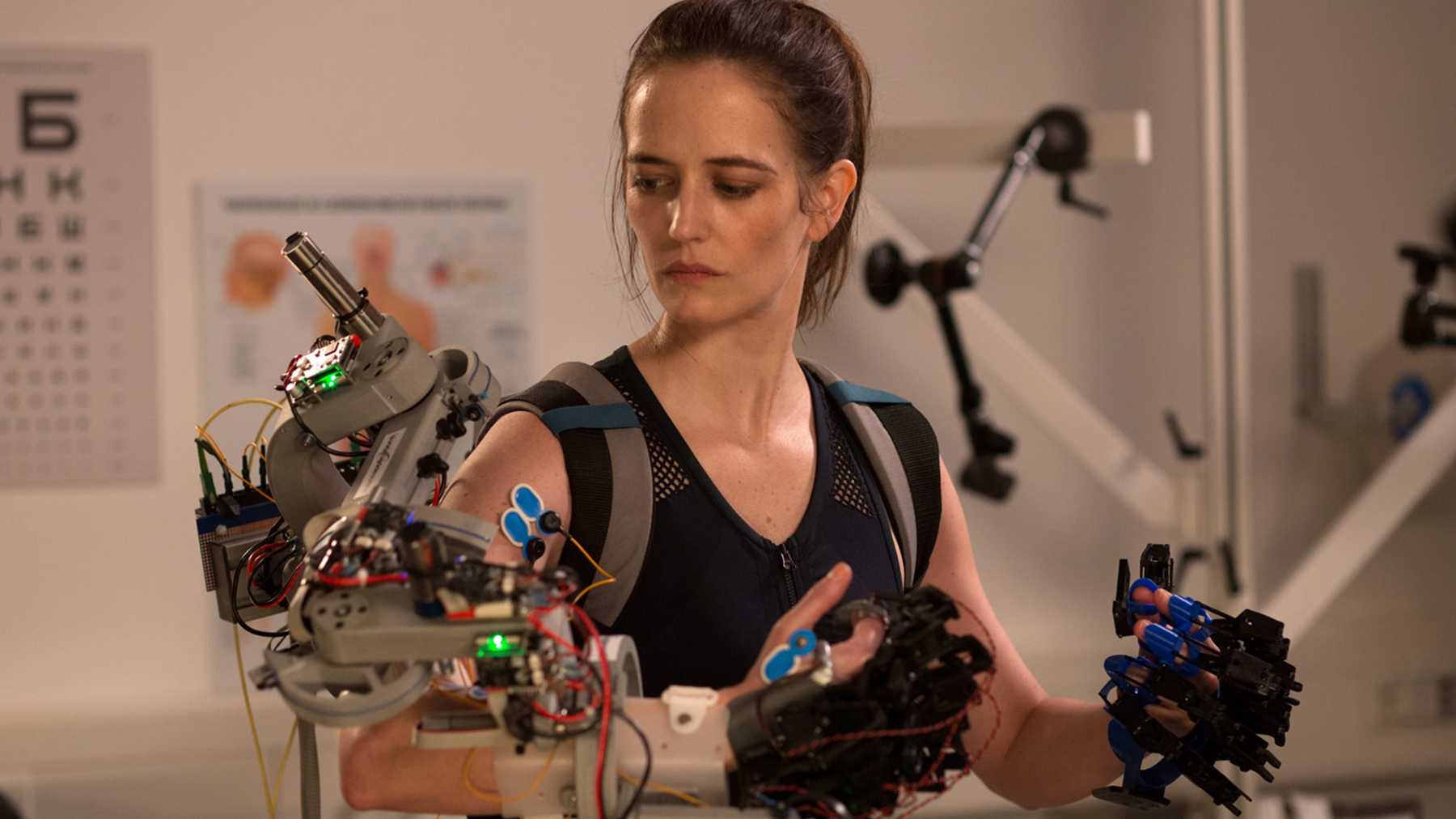

Green’s layered performance of female strength rebukes Hollywood's erotic exotic typecasting, letting rage and tears ripple through her then striding on. Men aren’t Sarah’s enemies, but privileged, different and to be negotiated: American crewmate Mike (Matt Dillon, pictured below right with Green) is a rangy, challenging cowboy whose space sexism is blatant, her German ex-husband Thomas (Lars Eidinger) sarcastic and grudgingly supportive. Dillon and Green’s eventually touching though chaste relationship strikes intimate sparks. Early interiors are lit dull lunar blue, emphasising earthbound apartments' enclosure. Director Alice Winocour filmed subsequent training at ESA’s real Cologne facility and Russia’s Star City. When Sarah’s car glides into the latter’s showpiece sprawl, as pine forests and blue minarets pass by her window, we are already in another world. Ryuichi Sakamoto’s score replaces dreamy synth washes with orchestral grandeur as this portal is passed.

Early interiors are lit dull lunar blue, emphasising earthbound apartments' enclosure. Director Alice Winocour filmed subsequent training at ESA’s real Cologne facility and Russia’s Star City. When Sarah’s car glides into the latter’s showpiece sprawl, as pine forests and blue minarets pass by her window, we are already in another world. Ryuichi Sakamoto’s score replaces dreamy synth washes with orchestral grandeur as this portal is passed.

The pressure of the looming mission makes lives bifurcate and translate themselves in other ways. Staying with Thomas in Cologne, Stella speaks German, to French Sarah’s dismay. The crew meanwhile find common cultural ground, with cosmonaut Anton and Mike swapping national poetry over a campfire. Sarah practises for an inverted life outside gravity, reading books backwards, and saying farewell to tears and sweat, though choosing to keep periods. Winocour has suggested Cronenberg as a comparison, and shows space voyaging as a process of cellular change. Sarah will be a literally different woman when she returns. Norman Mailer’s epic book on the Apollo 11 moon landing, Of a Fire on the Moon (1969), saw its crew as super-WASPs, ultimate avatars of disciplined, straight America during a time of hippie ferment. First Man similarly made Ryan Gosling’s Neil Armstrong super-cool, with sacred levels of sacrificial discipline. Proxima’s space hero requirements are less grand, and enmeshed with the domestic. Sarah spews blood after G-force testing, then calms Stella on the phone; the peace of space simulation contrasts with schoolgirl anguish. Raising a daughter and exploring space are a single, inseparable goal. Only Sarah's farcically sentimental, mission-endangering late favouring of the former betrays the film's previous careful work, and its feminism.

Norman Mailer’s epic book on the Apollo 11 moon landing, Of a Fire on the Moon (1969), saw its crew as super-WASPs, ultimate avatars of disciplined, straight America during a time of hippie ferment. First Man similarly made Ryan Gosling’s Neil Armstrong super-cool, with sacred levels of sacrificial discipline. Proxima’s space hero requirements are less grand, and enmeshed with the domestic. Sarah spews blood after G-force testing, then calms Stella on the phone; the peace of space simulation contrasts with schoolgirl anguish. Raising a daughter and exploring space are a single, inseparable goal. Only Sarah's farcically sentimental, mission-endangering late favouring of the former betrays the film's previous careful work, and its feminism.

Stella meanwhile watches and worries. “You knew your mother would go away one day?” she’s asked, lift-off and death linked. “First-stage separation” and “cutting the cord” add to the script’s shared metaphors for growing apart. We still powerfully sense that Mum is Stella’s hero, a female pioneer embodying their mutual ache for freedom. The few lyrical scenes studding Winocour’s often prosaic film show this. In one, Sarah stands in full spacesuit in a lake, grinning for Stella’s camera, surreal and stupendous. Later Stella walks across a lunar tableau, picking rocks, the first little girl on the moon.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Add comment