Cosmonauts: How Russia Won the Space Race / The Spaceman of Afghanistan, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Cosmonauts: How Russia Won the Space Race / The Spaceman of Afghanistan, BBC Four

Cosmonauts: How Russia Won the Space Race / The Spaceman of Afghanistan, BBC Four

A history of the Soviet space programme, and the story of one of its more unlikely participants

Cosmonauts: How Russia Won the Space Race (*****) arrived at a strange time. With its remarkable accumulation of Soviet archive material and interviews with key figures, including Alexei Leonov, the first man to walk in space, the programme must have been a long time in the making and the fruit of lengthy collaboration of a kind that might not be so readily forthcoming today.

Thus, there was a scene towards the end in which one of the more recent cosmonauts remembered his impressions on looking down at the darkness of the planet from space, and how the continents were distinguishable. Latin America was green with its forests, the American cities recognisable for the brightness of their grid systems; then there was “Russia with all its might pushing Europe towards the ocean,” and finally the “huge expanse of darkness” that was Russia itself.

It was, metaphorically, from that dark expanse that the Soviet space programme emerged: the Americans were quite simply amazed at its early achievements, marvelling that something so “astonishingly perfect” as Yuri Gagarin’s first manned space flight could come from what one US commentator referred to as a “backward nation of potato-farmers”. It’s easily forgotten how, in the early Sixties, such technical progress made the suggestion that the USSR and Communism would indeed outstrip the achievements of the capitalist world a very real one.

Both Gretchko and Alexei Leonov had a rather wonderful mordant wit to their memories

In such an environment the opposing powers were constantly comparing their achievements. The American development of the atomic bomb had Stalin pressing his scientists to come up with a counterbalance, but when they did it proved much larger in size, necessitating a rocket delivery system to match. Thus Sergei Korolev, the designer genius of the Soviet space programme, devised the R7 rocket, which was less well suited for carrying ballistic missiles but perfect as the basis for space exploration. From there on it was indeed a space race, with Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev pushing his scientists towards each new achievement. Space dog Laika was followed very soon by the smiling Gagarin, the first man in space (main picture: Yuri Gagarin with Sergei Korolev).

Running at 90 minutes Cosmonauts had the time to tell its story in detail as the competition continued, the next challenge being to get the first man on the moon. The film had second generation testimony from Natalya Koroleva, daughter of the scientist, and Sergei Khrushchev, son of the Soviet leader, and revealed that the USSR could have beaten the Americans to the moon. Asked by Khrushchev what such progress would cost, Korolev replied “it’s not important”, only to be rebuked: “It may not be important for you, but it is important for me.” Khrushchev was all too mindful that the Soviet standard of living had to be raised, and that the food industry needed the investment more than space.

What was lost with the moon was made up by Soviet advances in the development of the space stations like Mir, which saw scientists and engineers, like the personable Georgy Gretchko, interviewed here, sent into space to work for months on experiments, thus replacing the early generation of cosmonaut-explorers. Both Gretchko and Alexei Leonov had a rather wonderful mordant wit to their memories. Gretchko remembered how after plotting the launch axis for the very first Sputnik on the only computer in the USSR, he popped out for a sausage. “We didn’t appreciate what we’d done,” he recalled, and indeed that first launch was only covered with a small paragraph in Pravda, while it made headlines all around the world.

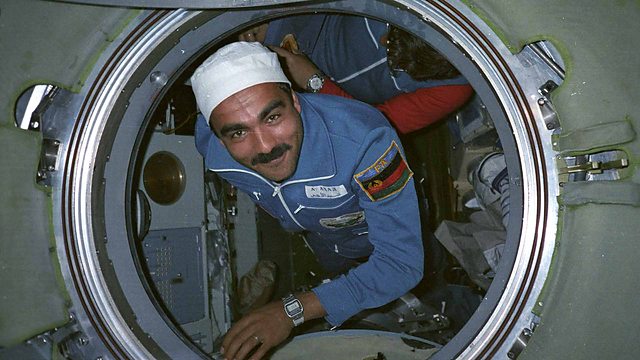

For a story from the Soviet space programme told in miniature, Janette Ballard’s engaging The Spaceman of Afghanistan (****) introduced us to Abdul Ahad Momand, the only Afghan to go into space. His boyhood journey from the remote countryside of his birth to become one of the top pilots in the Afghan air force seemed in some ways no less momentous than his 1988 mission to the Mir space station. “Fraternal” Soviet satellites were accorded such opportunities, and Ahad was one of those chosen to train at Star City, to which we saw him returning in very friendly circumstances to a reunion with his fellow cosmonaut Vladimir Lyakhov: their shared descent through the earth’s atmosphere proved distinctly hairy, but they survived thanks to some impro.

Ahad nearly didn’t make his flight, however: there was competition from a senior Afghan officer who had the bad luck to go down with appendicitis at the last minute. Political circumstances were far from favourable too, and the Afghan launch had to be hurried along; Perestroika meant that the Soviets would withdraw from Afghanistan less than a year later. Ahad returned home a hero, was duly appointed deputy minister of aviation in the Najibullah government, and fled abroad in 1992 only four days before that regime fell to the Mujahedin rebels (his wife movingly remembered how their return tickets remained in their bags for years).

Ahad nearly didn’t make his flight, however: there was competition from a senior Afghan officer who had the bad luck to go down with appendicitis at the last minute. Political circumstances were far from favourable too, and the Afghan launch had to be hurried along; Perestroika meant that the Soviets would withdraw from Afghanistan less than a year later. Ahad returned home a hero, was duly appointed deputy minister of aviation in the Najibullah government, and fled abroad in 1992 only four days before that regime fell to the Mujahedin rebels (his wife movingly remembered how their return tickets remained in their bags for years).

He’s long been living in Germany with his growing family, and now works as an accountant. Ballard’s film took him not only to Moscow, but back to Kabul, where he clearly felt some initial confusion. There was a reunion with his former rival for that space trip, now a general in the Afghan airforce (one which does not, however, have any fighter planes), and as word of his return spread, even a meeting with then president Karzai who would later bestow a medal. One of the ex-Mujahedin he encountered remembered how, although they’d been on different sides, he still felt proud for his country when this unlikely spaceman completed his journey.

Ahad proved a modest subject, and the dynamics of friendships and family were well conveyed. Outside commentators included Rodric Braithwaite, Britain’s final ambassador to the Soviet Union who's now an expert on that country’s Afghan escapade, and – for no particular reason I could fathom, except that it was another “first” – astronaut Helen Sharman, Britain’s first woman into space.

The film’s conclusion saw Ahad meeting young members of a Kabul astronomy association on a dark hillside outside the city to observe the stars. They had to take out a car battery and hook it up to the telescope, but it worked, and left Ahad expressing his hopes for a young generation. You suspect his optimism may be tempered, however, given that, remembering his nine-day space trip (pictured above right), he came out with the best line in the film: “I saw a peaceful Afghanistan from this height.”

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

Add comment