Der Freischütz, Bavarian State Opera online review – marksmen as marketeers | reviews, news & interviews

Der Freischütz, Bavarian State Opera online review – marksmen as marketeers

Der Freischütz, Bavarian State Opera online review – marksmen as marketeers

Tcherniakov’s staging heightens the psychological drama, but his feminist angle falls flat

Bavarian State Opera has led the way for live performances and associated broadcasts during the pandemic. Their series of weekly “Montagsstück” events have presented innovative chamber operas, specifically for web streaming. Their next goal is full-size opera with a live audience. That is not possible yet, so instead they are premiering a new production of Weber’s Der Freischütz.

The production is directed and designed by Dmitri Tcherniakov. He has spent the last 20 years cultivating a reputation as an enfant terrible. The result, ironically, is that he has developed a clearly recognisable vocabulary of devices and signs that clearly mark out his work. Typically, then, this is a modern-dress staging, and during the Overture, we are presented with projections of each of the main characters, along with descriptions telling us how the director has reimagined the roles. The setting is a large foyer of an executive office – it’s a single-set staging – where Kuno (Agathe’s father, sung by Bálint Szabó) is the CEO. We are told that Max (Pavel Černoch) is an employee, aspiring to promotion. Caspar (Kyle Ketelsen) is a senior executive; he’s also a war veteran with PTSD. Kuno and Agathe (Golda Schultz) are estranged, due largely to the influence of Ännchen (Anna Prohaska, both pictured below), a friend rather than cousin of Agathe, who previously helped her to distance herself from her overbearing father.

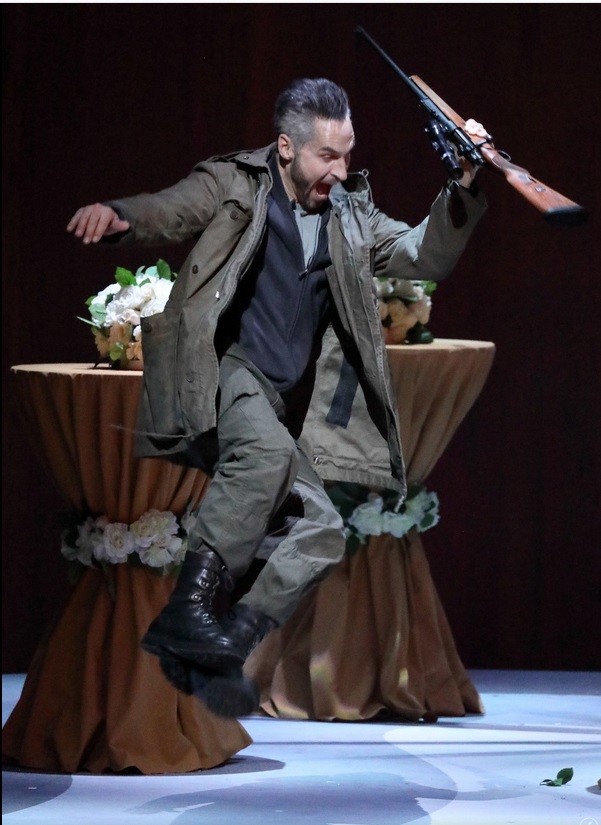

Clearly, then, the opera’s rustic folk setting is all but abandoned. But Tcherniakov is always sensitive to the conventions he is breaking, and every anachronism is cleverly integrated into the Konzept. So, for example, the spirited folk dance mid-way through the first act is here danced by Max alone, as a frenzied act of release from the social constraints of the office environment. The narrative’s central theme of a shooting contest sits uneasily with Tcherniakov’s setting, but he is typically confrontational – the shooting contest at the opening of the opera is presented as Max and the “peasant” taking pot shots out of the office window with a rifle, and the peasant shooting a passer-by in the head. The event is explained away later on, but it’s a powerful opening gesture.

Clearly, then, the opera’s rustic folk setting is all but abandoned. But Tcherniakov is always sensitive to the conventions he is breaking, and every anachronism is cleverly integrated into the Konzept. So, for example, the spirited folk dance mid-way through the first act is here danced by Max alone, as a frenzied act of release from the social constraints of the office environment. The narrative’s central theme of a shooting contest sits uneasily with Tcherniakov’s setting, but he is typically confrontational – the shooting contest at the opening of the opera is presented as Max and the “peasant” taking pot shots out of the office window with a rifle, and the peasant shooting a passer-by in the head. The event is explained away later on, but it’s a powerful opening gesture.

Much of the spoken dialogue is retained – it’s usually the first thing to go in a Regie reimagining – but Tcherniakov finds creative ways to both interpret and present it. In the first act, Max’s spoken confessions to the audience are instead projected as text above the stage, allowing the narrative and music to flow without interruption. In the second act, the dialogue between Agathe and Ännchen is both sung and texted, the two characters typing away on their phones and the texts again appearing above the stage. But Tcherniakov goes further, and the texts diverge significantly from the libretto. The idea here is to reimagine Ännchen as a divisive influence, rather than just the meek companion for Agathe. This dynamic is intended to highlight power struggles within the family, and that also seems to be the reason for the corporate setting. It’s more about hierarchy than commerce, and the production never aims at a critique of capitalism. But the Agathe/Ännchen dynamic doesn’t really work. Weber and his librettist weren’t feminists, and were happy to present social dynamics of their hunting community without criticism, so Tcherniakov has little to work with, in the end trying to resolve the tension he has created through more above-stage texts in the final act, even as the action moves in unrelated directions.

More effective is the presentation of Caspar. Tcherniakov related in a pre-performance interview that he did not read the story as a conflict of Good and Evil, but simple one of human weakness. So there is no Samiel – it’s all in Caspar’s head. That idea is projected powerfully in the Wolf’s Glen scene, where Caspar speaks and sings both parts of the dialogue with Samiel as if it were a schizophrenic episode. It is a chilling effect, beautifully realised by Ketelsen.

Tcherniakov manages to bring all these threads together in the final act. There is a massive twist, of course, but I won’t give it away. In fact, the libretto is quite weak towards the end – the denouement with the Hermit always seems tacked on – so the radically changed ending here feels like the director is doing the opera a genuine service. That said, if this was playing in front of a live Munich audience, the booing would have drowned out the applause.

Musically, this is an imaginative reading, with conductor Antonello Manacorda finding lightness and clarity in the score, and reserving the dark, bass-heavy textures for the moments in the story that really need them. The cast is competent throughout, though with few big names. As Max, Pavel Černoch is agile of tone and able to convey the complex emotions that the director projects onto the character. Golda Schultz is warm and expressive as Agathe. Manacorda puts aside his Classical reserve every time she sings, and the music immediately turns lush and Romantic, much to her benefit.

The greater dramatic significance that Tcherniakov places on Ännchen is handled well by Anna Prohaska. Prohaska has a more commanding vocal presence than Schultz, but the difference in tone between them makes for effective discourse. Best of all is Kyle Ketelsen as Caspar. His voice is rich and powerful, but he keeps most of that in reserve, giving a sense of tenuous control to each of his utterances, which conveys the depth of his psychological turmoil.

Tcherniakov is clearly playing to the strengths of his cast, perhaps even casting against type to heighten his tensions with the text (it is surely no coincidence that both Černoch and Schultz are making their role debuts). That speaks of a subtlety to his art, at odds with both his reputation and with the violent acts that he regularly portrays. If you like what he does, this Freischütz is classic Tcherniakov, with lots of experimental ideas, most of which hit their mark. If you don’t like his schtick, the production is unlikely to convert you to his cause.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Add comment