Henry Woolf's place in theatre history is small but significant, a bit like Woolf was himself. Until his death on November 11, at the age of 91, he was the last survivor of a gang who made friends at Hackney Down grammar school in the 1930s. The most famous member of the group was Harold Pinter. The Room, Pinter’s first play, was more or less commissioned by him.

“Commissioned is an awfully grand word,” Woolf told me when I first met him in 2000. In 1957 he was a postgraduate at Bristol when the new drama department was looking for one-act plays. Pinter was a freshly married actor, toiling pennilessly on the repertory circuit in Torquay. He had mentioned to his pal that he had an idea for a play. “I told a fib,” Woolf recalled, “that I knew a brilliant play, because it wasn’t written yet. The clincher was I said it wouldn’t cost them anything. I said to Harold, ‘Write it. I’ve managed to con them.’ Harold wrote back saying, ‘I can’t write a play in under six months.’ He actually wrote it in two days.” For the rest of his writing life Pinter sent Woolf every fresh manuscript.

The Room was premiered in a converted squash court (pictured below with Henry Woolf in the centre). It was directed by Woolf. He also played Mr Kidd, an elderly man who claims somewhat vaguely to be landlord of a quiet suburban house with rooms to let. He was 28 at the time. Pinter recalled that his friend “wasn’t bad”. He returned to the role when the author directed him in the first professional production at Hampstead Theatre Club in 1960. I once asked Pinter what he remembered of his old chum’s performance. “He was a bit in and out,” he unimprovably replied. Henry Woolf was remarkably short – short enough to play Toulouse-Lautrec in a West End musical. He compensated with energy and enthusiasm. “He was a hell of a livewire when he was 17,” Pinter told me. “He had of course a tremendous wit. Henry was a great table tennis player. He was very cunning. Used to lob it up from under the table. A lot of spin.” “My strokes,” Woolf said, “were redolent of a kind of Hebraic ambiguity.” Pinter’s style, he added, “was completely unorthodox, unlike anybody else's.”

Henry Woolf was remarkably short – short enough to play Toulouse-Lautrec in a West End musical. He compensated with energy and enthusiasm. “He was a hell of a livewire when he was 17,” Pinter told me. “He had of course a tremendous wit. Henry was a great table tennis player. He was very cunning. Used to lob it up from under the table. A lot of spin.” “My strokes,” Woolf said, “were redolent of a kind of Hebraic ambiguity.” Pinter’s style, he added, “was completely unorthodox, unlike anybody else's.”

Their friendship seemed from the outside to be based on an attraction of opposites. But Woolf portrayed Pinter as a generous, loyal man starkly at odds with the received image of a glowering curmudgeon. Among his many kindnesses, in Woolf’s eyes, was to cast him in Monologue, a short drama for the BBC, in 1973. “He could have got any actor, who would have given their left frontal lobe to play a Pinter monologue on TV, but he gives it to H Woolf. You know how I rewarded him? By giving one of the worst performances ever seen on television. Harold never said a word.”

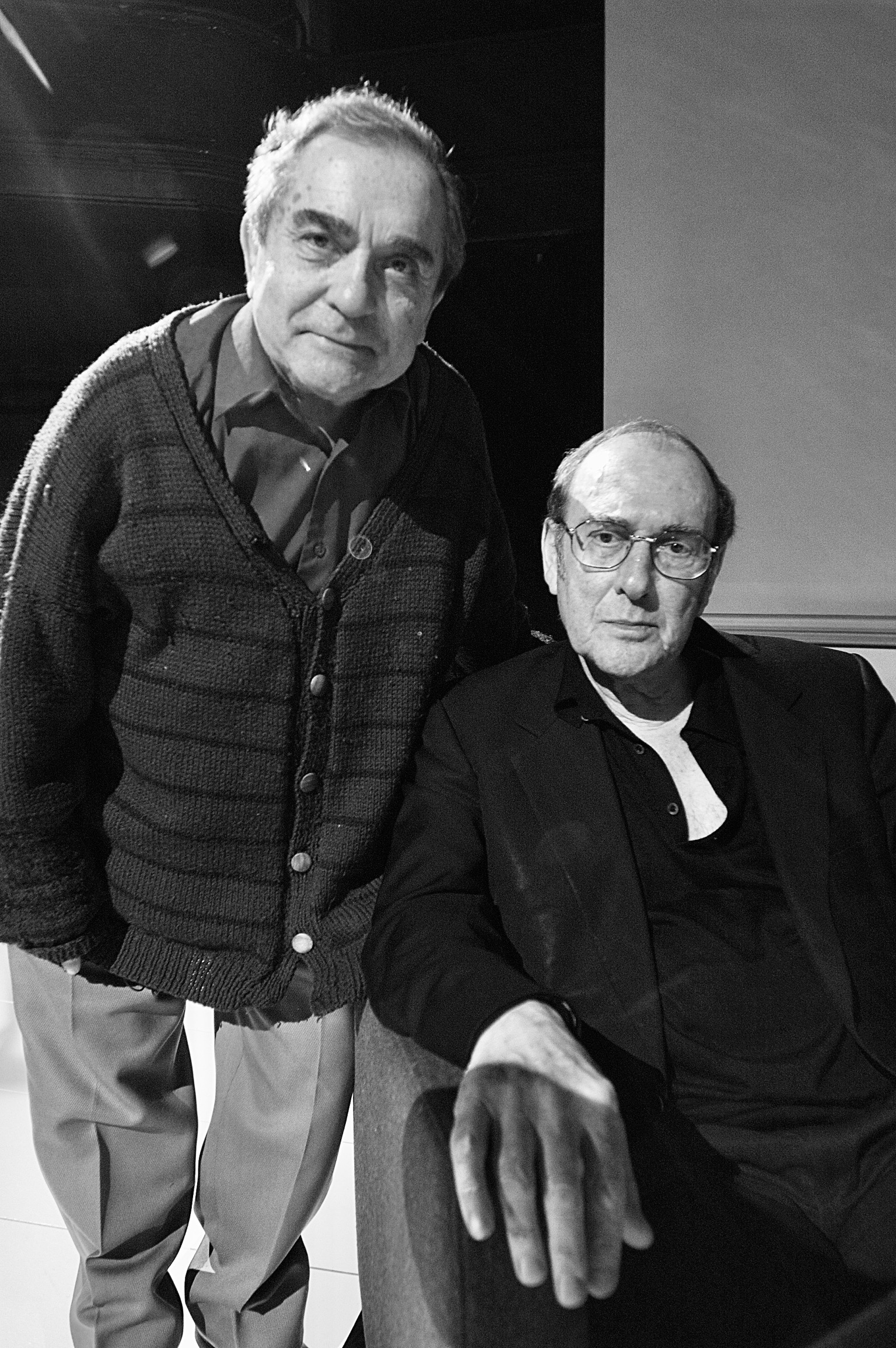

Woolf and Pinter (pictured below together by Gavin Watson) were part of a group of mostly Jewish friends from the East End. The bond was mostly based on left-wing post-war idealism and intellectual self-improvement. Woolf, especially, was politicised from an early age. With his parents, who left Romania in 1913, he remembered following the Spanish Civil War as a five-year-old; at the same age, he was hit on the head with a tennis racket by the daughter of the neighbour, one of Mosley’s lieutenants. “She said, ‘Oh it’s nothing personal, it’s because you’re Jewish.’ It was a Jewish world we grew up in in the sense that if someone chases you down the street with half a brick because you’re a Jew, then it’s a Jewish world. But we all gravitated away from our traditional origins.”

Pinter was always the leader. In their first conversation, he lent Woolf a novel by Henry Miller. “When he was an out-of-work actor without tuppence for a cup of tea, he actually had exactly the same charismatic effect on us. We criticised him constantly, because he was ahead of us – with girls, in reading.” When Pinter became a conscientious objector, refusing to do National Service, his father blamed Woolf. “Henry saw the point I was making,” said Pinter, “and he was very supportive.” “I always used to encourage Harold,” Woolf remembered. “His father said, ‘If he comes round, I’ll knock him downstairs.' But I turned up with classic timing about 10 minutes after he’d said that. Jack Pinter, who was a lovely bloke, opened the door and said, ‘Come in, Henry, have a cup of tea.’”

Pinter was always the leader. In their first conversation, he lent Woolf a novel by Henry Miller. “When he was an out-of-work actor without tuppence for a cup of tea, he actually had exactly the same charismatic effect on us. We criticised him constantly, because he was ahead of us – with girls, in reading.” When Pinter became a conscientious objector, refusing to do National Service, his father blamed Woolf. “Henry saw the point I was making,” said Pinter, “and he was very supportive.” “I always used to encourage Harold,” Woolf remembered. “His father said, ‘If he comes round, I’ll knock him downstairs.' But I turned up with classic timing about 10 minutes after he’d said that. Jack Pinter, who was a lovely bloke, opened the door and said, ‘Come in, Henry, have a cup of tea.’”

In a sense Woolf’s whole life was shaped by Pinter. Pinter recommended Woolf for his first acting job, although not before he’d sent a note saying, “What do you want to go into this shithouse of a profession for? You’ll meet very few people you want to have a drink with.” In 1974, the year after Monologue, he was invited to Canada to act in an adaptation of The Dwarfs and direct The Lover in a Pinter double bill. In Sasktatoon, where he became a professor of drama, he directed the North American premiere of Ashes to Ashes.

The acting career he left behind had some spectacular highs ranging from Peter Brook’s Marat/Sade to The Rocky Horror Picture Show. In the touring production of Chimes at Midnight he played Nym to Orson Welles’s Falstaff. “I got on terribly well with Orson. Partly because I only reached up to his knee. It was what I call a fetlock performance. On the first night in Belfast the Lord Chief Justice didn’t come on when he was supposed to. Orson and myself were alone onstage. Orson began to palpitate a bit. So I said, ‘Get thee behind me, sir.’ This giant! We managed to get quite a few laughs.”

Welles also cast Woolf in the British premiere of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros at the Royal Court, starring Laurence Olivier. “There was a silent contest for authority. Olivier’s iron courtesy never bore any sign of fraying. I remember once approaching the eminence in the wings. He’d just got us tickets to see him in The Entertainer. So I said, ‘Sir Laurence, thank you so much, it was a marvellous performance.’ He turned round to see who was speaking – these huge empty eyes, to be filled with this electricity the moment he stepped onstage – and saw that I was a creature of utter insignificance and said, ‘I am so pleased you’re pleased.’ And turned back. I shrivelled. I used to be a tall fair chap until that moment.”

It was Olivier who indirectly ignited Woolf’s interest in acting. He attended a wartime production of Arms and the Man in the West End during a bombardment of V1 and V2 rockets. “The theatre kept shaking with explosions and these huge candelabra swung over the stalls. We were all of us risking our lives to see an anti-war play. And Olivier would pause while the reverberations stopped and the plaster stopped falling. That was my first temptation.”

He twice came back to London to appear in plays by Pinter. At the age of 70 returned to the role of Mr Kidd when the Almeida revived The Room in a double bill alongside the premiere of Celebration. Then in 2007, when the National Theatre revived The Hothouse, Woolf took the small comic role of Tubb. As with The Room there was a back story to his involvement.

The first time he heard about The Hothouse was when Pinter had just endured a critical drubbing for The Birthday Party, his first professionally staged play. “I was living in a typical bedsit somewhere in Canonbury. He came in naturally rather deflated and he said, ‘You know what I’ve done.’ ‘What?’ He said, ‘I’ve written another play. I’m not sure if it’s right. I’m going to put it away for a bit.’ It struck me as an extraordinary act of moral courage.” The play was not premiered for another 23 years.

Woolf suspected that “there could be a bit of echo of my unworthy self in Monologue”. His character likes a game of ping pong and also boasts, “I’ve got a hundred per cent more energy in me now than when I was 22.” Henry Woolf to a tee.

- Listen to Henry Woolf on Working with Pinter, a series of interviews conducted by Pinter specialist Harry Burton

Add comment