Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Royal Academy review – a life lived in extremis | reviews, news & interviews

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Royal Academy review – a life lived in extremis

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Royal Academy review – a life lived in extremis

From raw emotion to elegant displays of self loathing

Francis Bacon Man and Beast fills most of the main galleries at the Royal Academy. Thankfully, five of the rooms are empty. The exhibition is such a dispiriting experience, I’d have been hollering like a howler monkey if there’d been any more. And as it was, I came out feeling emotionally numb.

It’s not what Bacon intended. He hoped his paintings would “unlock the valves of feeling and therefore return the onlooker to life more violently.” Maybe you need a penchant for violence to respond as he hoped since, for him, living life violently was the norm. When his military father discovered his son trying on his mother’s clothes, he took to beating the sissy out of him. And it turned Bacon into a sadomasochist.

The first room is devoted to a single painting, Head I,1948 (pictured below right). What first grabs you are the bared teeth inside the open mouth. The red lips and tongue are the only touch of colour in this image of a figure sitting in a bare room. Despite the snarl, he seems less threatening than contorted with fear or pain. The left side of the head is human and dangling above his beautifully observed ear is a tassel, a light pull perhaps – a touch of normalcy in an otherwise bleak space. Based on a photo of a chimpanzee, the right side is animal. The fusion suggests that if you peel away the flimsy veneer of civilisation, you reveal our baser instincts.

The picture was part of a series painted by Bacon for his first exhibition and it contains many of the devices he would use again and again throughout his career. Boxes of space resembling rooms, cages, pens, daises, thrones or beds contain figures in which human and animal features merge and morph into creatures contorted with anguish, pain, fear, lust or self loathing.

The picture was part of a series painted by Bacon for his first exhibition and it contains many of the devices he would use again and again throughout his career. Boxes of space resembling rooms, cages, pens, daises, thrones or beds contain figures in which human and animal features merge and morph into creatures contorted with anguish, pain, fear, lust or self loathing.

Mundane props like a tassel, door knob, umbrella or bunch of flowers make the horrifying vulnerability of these specimens appear normal. Stripped of clothing and robbed of status, people are revealed to be naked apes cursed with the guilt, shame, remorse or disgust that self consciousness can bring.

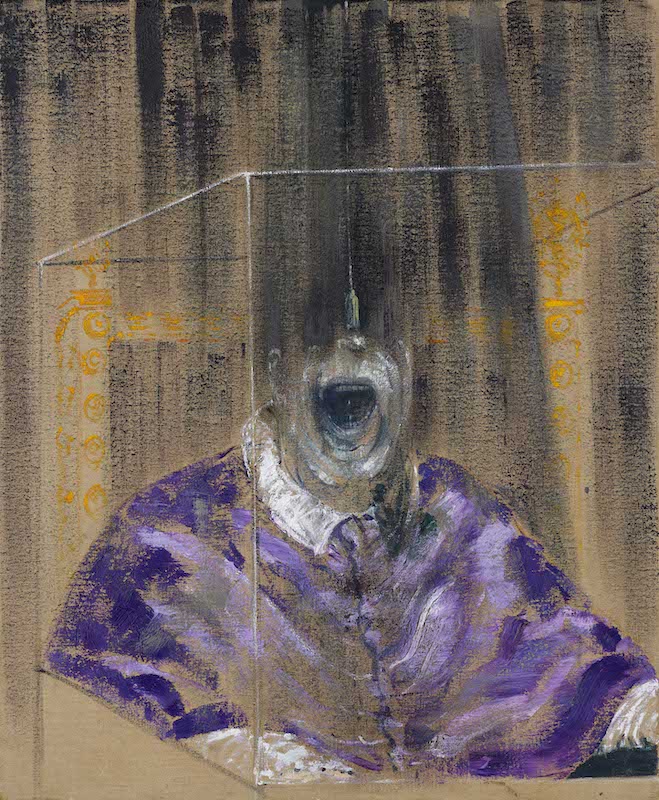

Some of the early works are really powerful. Head VI, 1949 (pictured below left) is the first of nearly 50 versions Bacon made of Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1650. The pontiff’s purple robes are clear, but like the Cheshire cat, the man is rapidly disappearing. What’s left is his mouth, wide open in a scream muffled by the glass box in which he is incarcerated. “I like”, Bacon once said, “the glitter and colour that comes from the mouth, and I’ve always hoped in a sense to be able to paint the mouth like Monet painted a sunset.” The Pope’s mouth is not a sensual delight, though, but an arid chasm leading only to inner darkness.

Then there’s the naked man kneeling on a strip of spiky grass rolled out like a carpet of nails. He seems lost in an inhospitable void, like an animal in a zoo. There’s also the white dog walking beside its owner. No clichés here, just a strip of black sky, grey pavement, dark grey gutter and blue grey road. Behind the dog, the man is nothing but a dark smudge or shadow while beneath the dog is a drain. The picture suggests a Beckett-like view of life as a dreary, monochrome journey, which ends in being flushed down the drain.

The dog is based on a photograph by Edweard Muybridge, published in 1887 as part of an extensive series exploring human and animal locomotion, which Bacon frequently used as a source. Two Figures, 1953 were borrowed from Muybridge’s photographs of wrestlers. By portraying them on white sheets, Bacon turns them into a pair of lovers and by putting them in a glass box, he suggests they are on display.

Voyeurism is an ongoing theme in the work. Bacon referred to viewers as “onlookers” and over the years he invites us to keep watching as his subjects writhe, twist and contort in naked anguish on beds, sofas, chairs, bar stools and lavatories. In the early work we seem to be privy to private moments of doubt or shame. Gradually, though, a sense of spectacle takes over. The boxes become more like display cases, podiums, arenas, rooms or even sets within which his subjects dissolve into pools of disintegrating flesh.

Voyeurism is an ongoing theme in the work. Bacon referred to viewers as “onlookers” and over the years he invites us to keep watching as his subjects writhe, twist and contort in naked anguish on beds, sofas, chairs, bar stools and lavatories. In the early work we seem to be privy to private moments of doubt or shame. Gradually, though, a sense of spectacle takes over. The boxes become more like display cases, podiums, arenas, rooms or even sets within which his subjects dissolve into pools of disintegrating flesh.

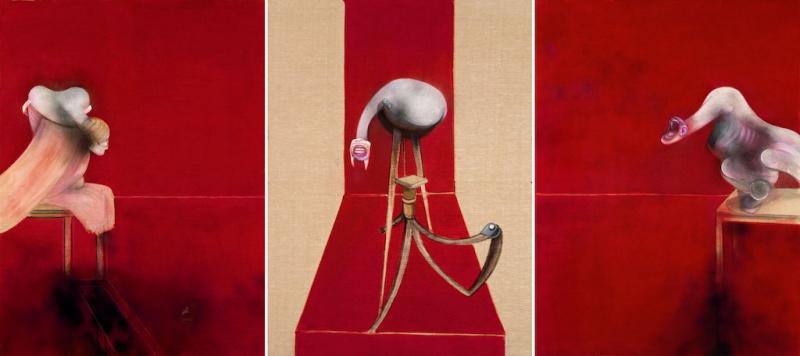

The more colourful, the slicker and more clichéd the paintings become, the less they have emotional heft. His 1988 remake of Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, for instance, has been refined to the point where the shocking rawness of the 1944 original is replaced by elegance (main picture). The harpy in the central panel now poses on a red carpet as if it were a monstrous celebrity or fashion model, while its pedestal resembles a camera stand. Has the crucifixion morphed into a fashion shoot ?

Bacon started out as an interior designer and, in my view, ended up designing paintings of interiors that resemble sets. This is theatre – human misery and despair presented for our delectation as spectacle. Raw emotion has been sacrificed to stage craft. And this, as I've described it in the past, is designer angst.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment