Francis Bacon: Couplings, Gagosian Gallery review - sex and power in double figures | reviews, news & interviews

Francis Bacon: Couplings, Gagosian Gallery review - sex and power in double figures

Francis Bacon: Couplings, Gagosian Gallery review - sex and power in double figures

A small selection focuses on the painter's radical figure paintings

Bacon explores the relationship between two bodies, and specifically two male bodies – though gender is often left in doubt – with a frankness that feels like a physical blow. Vulnerability and intimacy are brought up short by brute strength: primal, animal, but very recognisably human.

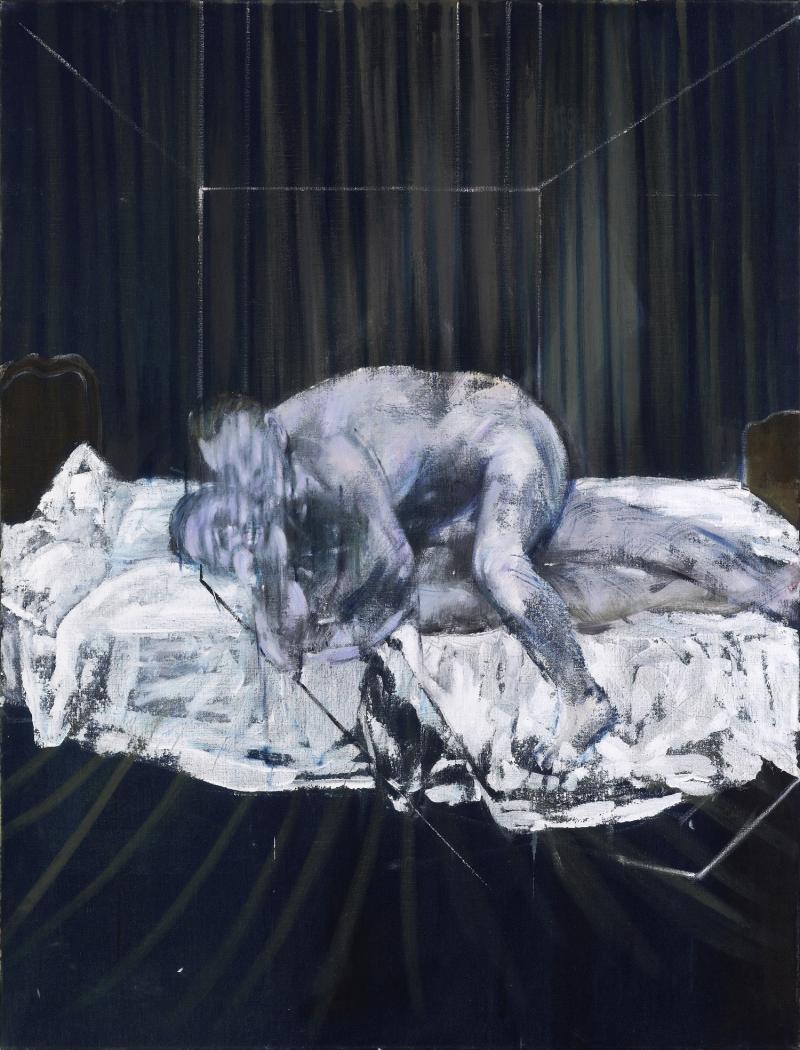

Among the photographs, torn-out pages and press cuttings used by Bacon as visual sources, the motion studies of wrestlers by 19th century photographer Edweard Muybridge are key. Bacon’s Two Figures, 1953 (Main picture), are wrestling alright: in fact in 1953, 14 years before the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK, some viewers were content to see it as a painting of wrestlers and no more. It’s ironic then that though the wrestling figures once gave the painting a semblance of respectability, their adversarial embrace is what makes the painting so unsettling. Their faces, contorted in a blur of ecstasy or agony, look out to us in a plea of need and desperation. Romantic ideas about sex are tossed aside: for Bacon, sex is power and there must always be a victor. In these scenes of battling, copulating figures the remorseless trajectory of a relationship bound for destruction is described in bodily fluids and a tangle of sheets.

Among the photographs, torn-out pages and press cuttings used by Bacon as visual sources, the motion studies of wrestlers by 19th century photographer Edweard Muybridge are key. Bacon’s Two Figures, 1953 (Main picture), are wrestling alright: in fact in 1953, 14 years before the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK, some viewers were content to see it as a painting of wrestlers and no more. It’s ironic then that though the wrestling figures once gave the painting a semblance of respectability, their adversarial embrace is what makes the painting so unsettling. Their faces, contorted in a blur of ecstasy or agony, look out to us in a plea of need and desperation. Romantic ideas about sex are tossed aside: for Bacon, sex is power and there must always be a victor. In these scenes of battling, copulating figures the remorseless trajectory of a relationship bound for destruction is described in bodily fluids and a tangle of sheets.

Sometimes, only one figure is discernible, as in Figures in a Landscape, c.1956. Here two bodies resemble only one, painfully contorted, or perhaps a collection of dismembered body parts, with the second figure overwhelmed by the first and reduced to a pair of legs. It’s as if sex – the “bed of crime” as Bacon called this theme – requires the annihilation of one or other party, the wrestling match that precedes it not so much a rough game, as a battle for survival (Pictured above right: Two Figures on a Couch, 1967).

Bacon’s “male couplings” are inevitably inflected with autobiography, and his two most significant love affairs, with Peter Lacy in the 1950s and then George Dyer in the 1960s were both violent, his dominance of Dyer so complete that according to Bacon scholar Martin Harrison, Dyer’s personality was “cancelled out”. However such characteristics resonate through Bacon’s work, it would be a mistake to think of him simply diarising his relationships, or documenting his pathologies. Instead, fundamental preoccupations, such as the destructive alchemy of human relationships find new voice in paintings like the walking man. Here we find ourselves confronted by a ghostly, besuited man who walks directly at us. Insubstantial and frankly two-dimensional as he is, it is an intimidating encounter with a malign and voracious presence: a black hole in human form.

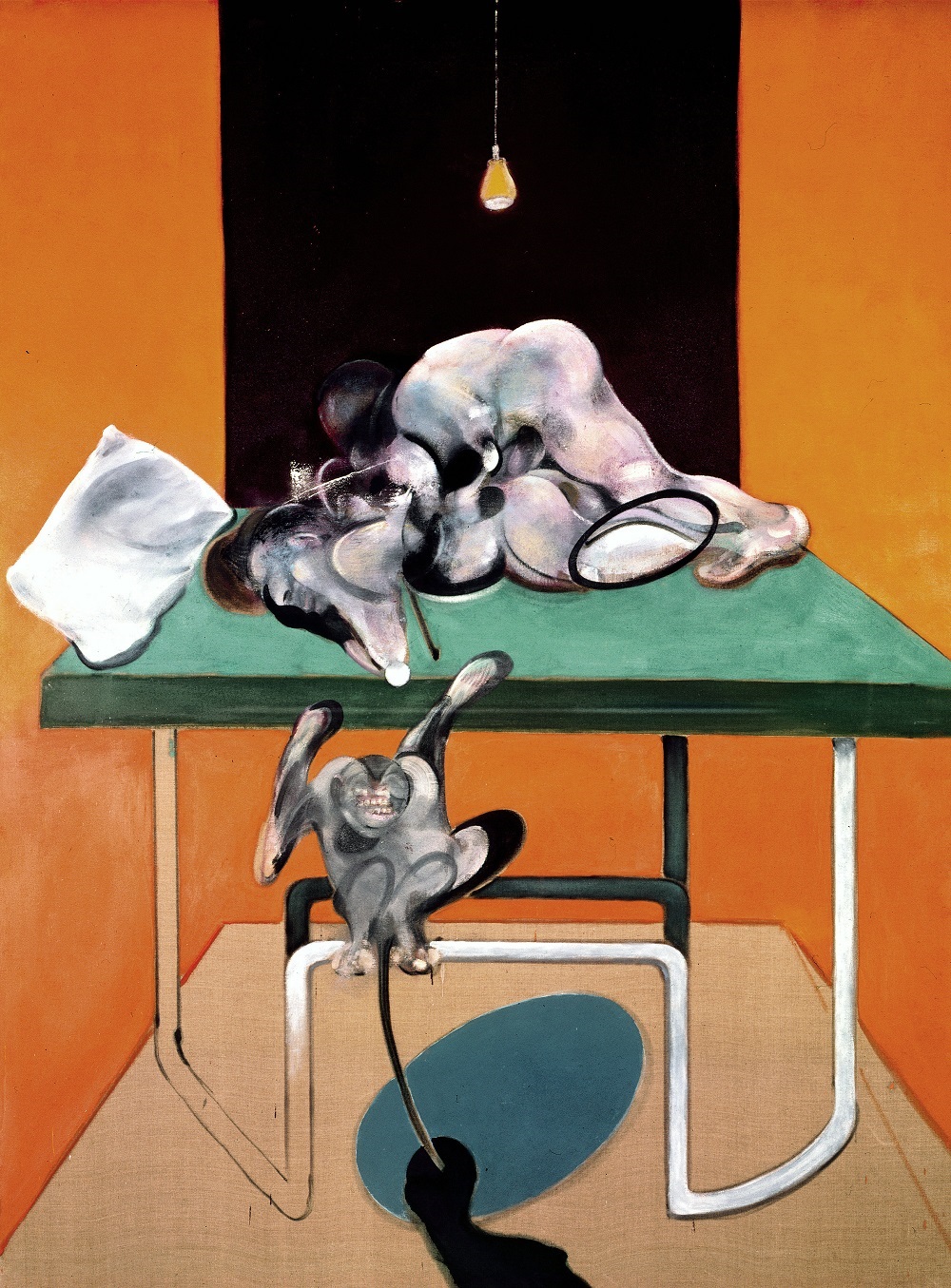

If one person can obliterate another, so an individual can be broken into fragments, with multiple figures representing aspects of a personality. Animal figures serve to disrupt and reveal: in Two Studies of a Human Body, 1975, we might be looking at a man and his (approximate) mirror image. The seated figure with his back to us though is distinctly ape like, a somewhat more advanced version of the heavily muscled body in the foreground. In Two Figures with a Monkey, 1973 (Pictured left), a screaming monkey makes a terrifying inquistor, apparently demanding a reaction from us as it crouches between us and two lovers on a clinical green table.

If one person can obliterate another, so an individual can be broken into fragments, with multiple figures representing aspects of a personality. Animal figures serve to disrupt and reveal: in Two Studies of a Human Body, 1975, we might be looking at a man and his (approximate) mirror image. The seated figure with his back to us though is distinctly ape like, a somewhat more advanced version of the heavily muscled body in the foreground. In Two Figures with a Monkey, 1973 (Pictured left), a screaming monkey makes a terrifying inquistor, apparently demanding a reaction from us as it crouches between us and two lovers on a clinical green table.

In this painting, a strange, disembodied shadow lurks under the table, a presence that seems substantial and unsettling enough to be counted as a further figure in this already overcrowded scene.

One of Bacon’s most intriguing works, Painting, 1950, also uses a shadow to create uncertainty and the sense of a lurking, other presence. Here the shadow is clearly that of a man, and yet it does not belong to the indeterminate, though probably female figure before us, whom we see, illicitly, through partially closed curtains. Named after his own occupation, the work casts the painter – and viewer – as voyeur, complicit in the exertion of power over the painted subject. Confused spatial arrangements and an ambiguous narrative begin to set out some of the possibilities and limitations of the art of painting and in doing so serve as a reminder that however horrifying and apparently pertinent Bacon’s personal life was, it is ultimately through his paintings that we must consider him.

- Francis Bacon: Couplings at Gagosian Gallery, Grosvenor Hill until 3 August 2019

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment