Dogs of Europe, Belarus Free Theatre, Barbican Theatre review - doom art with doom reality | reviews, news & interviews

Dogs of Europe, Belarus Free Theatre, Barbican Theatre review - doom art with doom reality

Dogs of Europe, Belarus Free Theatre, Barbican Theatre review - doom art with doom reality

An apocalyptic vision of an insatiable, all-obliterating Russia has dreadful timeliness

Hindsight is everything. In the light of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, political intrigues have suddenly taken on a far more menacing face, disbelief has been pulverised by reality – and theatre has become actuality.

A few weeks ago, the Belarus Free Theatre’s Dogs of Europe was listed at the Barbican as a psychological drama set in a dystopian near future, a “fantasy and political thriller about the dangers of looking away when authoritarianism takes root.” The thrill of doom art without doom reality.

But at the weekend the production seemed to have been projectile-vomited onto the stage by events. Staged by refugee performers who have all been penalised by the Lukashenko government and are now exiled in London, its three-plus hours howled and groaned, a chaos of fearful scenes of cultural catastrophe whose impact on the senses one would ordinarily compare – not thinking too much about it – with the experience of being bombed or brainwashed. Except that those comparisons can’t be made any more, and it's impossible to use usual critical criteria.

Based on a novel by Alhierd Bacharevič that was banned in Belarus, the play leaps between 2019 and 2049, where President Lukashenko’s ongoing reappropriation of Belarus for Russia leads to a future “Russian reich” that’s wound the clock back more than 100 years to Stalin’s Soviet Union, an absurdist, perpetually episodic, disconnected world populated by reprogrammed neo-Russians, where ignorance, suspiciousness and alcohol-fuelled inertia are the human condition, and books and ethnic languages are enemy material.

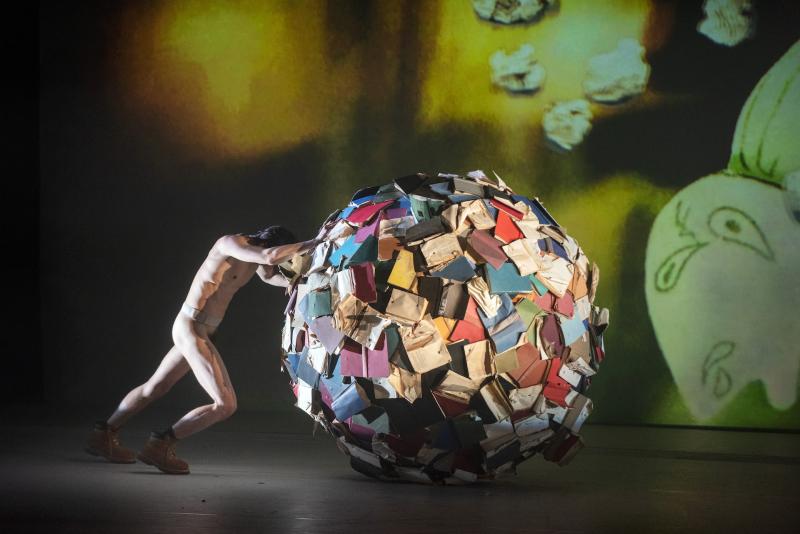

This depersonalisation and anti-civilisation is brilliantly rendered by some staggering digital animation and film work, which projects quasi-realist settings – a vast vacant hall, a grim little house, a blasted field – as if through a drunk’s eye view, always tottering or quivering, never steady, and sometimes decorating them with cute, scrappy scribbles and animated pandas. Childishness is never far away (pictured above, Aliaksei Naranovich and Raman Shytsko). The visuals – slightly reminiscent of Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python work – make you grab for stability, and their maniacal contrasts of bleakness and whimsy define the non-sense of the concept, disguising the rough and ready nature of some of the text and performing.

This depersonalisation and anti-civilisation is brilliantly rendered by some staggering digital animation and film work, which projects quasi-realist settings – a vast vacant hall, a grim little house, a blasted field – as if through a drunk’s eye view, always tottering or quivering, never steady, and sometimes decorating them with cute, scrappy scribbles and animated pandas. Childishness is never far away (pictured above, Aliaksei Naranovich and Raman Shytsko). The visuals – slightly reminiscent of Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python work – make you grab for stability, and their maniacal contrasts of bleakness and whimsy define the non-sense of the concept, disguising the rough and ready nature of some of the text and performing.

Buried somewhere in this cacophony is a two-act narrative split over some 30 years, linked by a time capsule jar prepared by giggling, cynical schoolchildren in the village of White Dews No 13 in modern Belarus. The kids sign their inconsequential letters; meanwhile soon all books will be erased of their titles and authors’ names, making every book look the same as every other, anonymised to meaninglessness, and mostly good only for burning. (A lot of time the theatre’s filled with the acrid smell of burning paper, and of the pungent cigarettes being chainsmoked by some of the cast.)

Meanwhile older lads are driven to desperate measures to discover their original identity. They jig in a raucous rap, and plan to buy a radioactive island to establish an independent state of Kryvia (the word echoes the Russian for “blood”). Shades of Golding’s Lord of the Flies – they seize on a crone in a wheelchair, making this granny their totem, a last source of true Belarusian blood and of the ethnic memories they seek.

One boy stumbles upon a parachutist who is a spy from “Spyland”, a land of much interest to the curious kid, but which we gradually discover to be an almost equally decayed "League of European States", whose democratic institutions have lost all meaning and direction. In the second act, 30 years later, the boy is now an official (the very good Aliaksei Naranovich) hunting fruitlessly through the remains of Europe for the identity of a poet whose verses he found in one of those anonymised books.

Bluntly speaking – very bluntly – it’s all gloom ahead, whichever way you look. The audience is pinned between the slogans of the invading force and of the decaying one. It’s less an argument than a shriek of inevitability.

Bluntly speaking – very bluntly – it’s all gloom ahead, whichever way you look. The audience is pinned between the slogans of the invading force and of the decaying one. It’s less an argument than a shriek of inevitability.

And it's also not easy to believe in a future Russian empire in 2049 (with a "tsar-emperor" at its head, we are told) that had simply wound back to a bestial state. In this future, all skill has ceased. Russian dancing is reduced to a couple of lame hops, music to hoarse folksongs or a one-armed accordionist maddeningly repeating the same motif. Women are timeworn clichés, girls being raped as a symbol for the violated Belarus (pictured right, Maryia Sazonava and Marichka Marczyk), wives being “appointed” to good citizens, or barmaids preying sexually on impotent men.

A lot of adjectives have identified this territory more originally before – Gogolian, Kafkaesque, Orwellian, Attwoodian. There have also been superior stage works about the unholy alliance of tyranny with banality – Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk is an obvious one, and the Derevo mime troupe (originally from St Petersburg, but exiled for being anti-social) has certainly delivered sharper and more imaginative physical theatre on apocalypse than this.

On the other hand, we were sitting in the theatre half-expecting news that Russian troops had begun to obliterate Kiev and Odessa and Putin had unleashed nuclear blitzkrieg. In these ominous circumstances Belarus Free Theatre's production is now doom art with doom reality, paying direct tribute to its Ukrainian brothers and sisters. Meanwhile the creator of their fantastic film and animation work, Roman Liubyi, who is Ukrainian, is out there in the real war right now.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment