First Person: composer Michael Price on responding to Bach's Second Brandenburg Concerto | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: composer Michael Price on responding to Bach's Second Brandenburg Concerto

First Person: composer Michael Price on responding to Bach's Second Brandenburg Concerto

'The Malling Diamond' is one of six commissions for an ambitious Music@Malling project

There are lots of ways that we respond to great works of art – intellectually and emotionally, then visually, aurally and even by taste and smell, depending on the art in question. I have a habit of screwing my eyes tight shut and bringing to mind a piece of favourite music, or book, or person, and it seems a glowing imprint forms behind your eyelids. You could try it now!

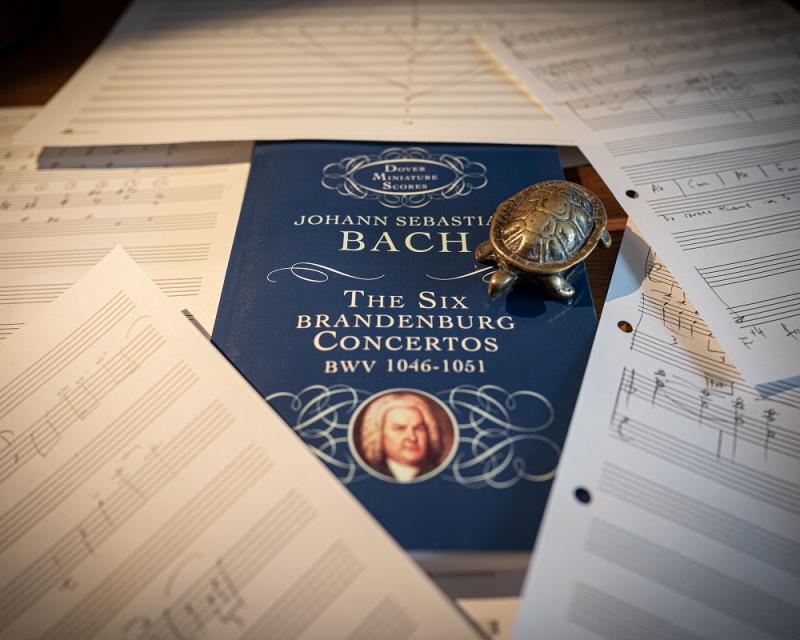

I’ve been fascinated with Bach’s Second Brandenburg Concerto since I was at school, mostly because I was a trumpet player, and Bach’s super-high trumpet part was regarded as the Mount Everest of brass playing – a peak I failed to scale many times. When I close my eyes and think of that summit, it often seems to sparkle and dazzle, and that was enough of a starting point to write The Malling Diamond, one of six commissions, each related to a Brandenburg Concerto, for Music@Malling.

Once writing began, it was a matter of building on that inspiration. Often the musical idiom of film and TV music is defined by the show and the story, and certainly influenced by the director and producers, but I’ve always had, I think, a core musical voice, from my first compositions as a kid. There’s a particular way of moving from note to note that I think is almost unconscious for composers, but when you add all the notes up, each starts to appear unmistakably their own. That’s what I try to do in my concert work: try and find the next right note to follow the one I’m on. Sometimes that takes quite a while.

Once writing began, it was a matter of building on that inspiration. Often the musical idiom of film and TV music is defined by the show and the story, and certainly influenced by the director and producers, but I’ve always had, I think, a core musical voice, from my first compositions as a kid. There’s a particular way of moving from note to note that I think is almost unconscious for composers, but when you add all the notes up, each starts to appear unmistakably their own. That’s what I try to do in my concert work: try and find the next right note to follow the one I’m on. Sometimes that takes quite a while.

One particular aspect of writing this piece included factoring in who the music was responding to. That is, the particular group of players Bach uses in Brandenburg Concerto No 2 – woodwind, strings, trumpet and harpsichord, in two separate groups. This particular line-up gives lots of possibilities for interesting combinations, but on the other hand, there are also a few balance issues. To make a particular instrument really stand out from the others, you need to dig a pretty big hole in the orchestration. There’s a section in the middle of the piece where a trumpet solo is accompanied by a low shimmer of strings, down at the bottom of their range to really let the trumpet shine out over the top. In other places, each of the players has an equal role in matters.

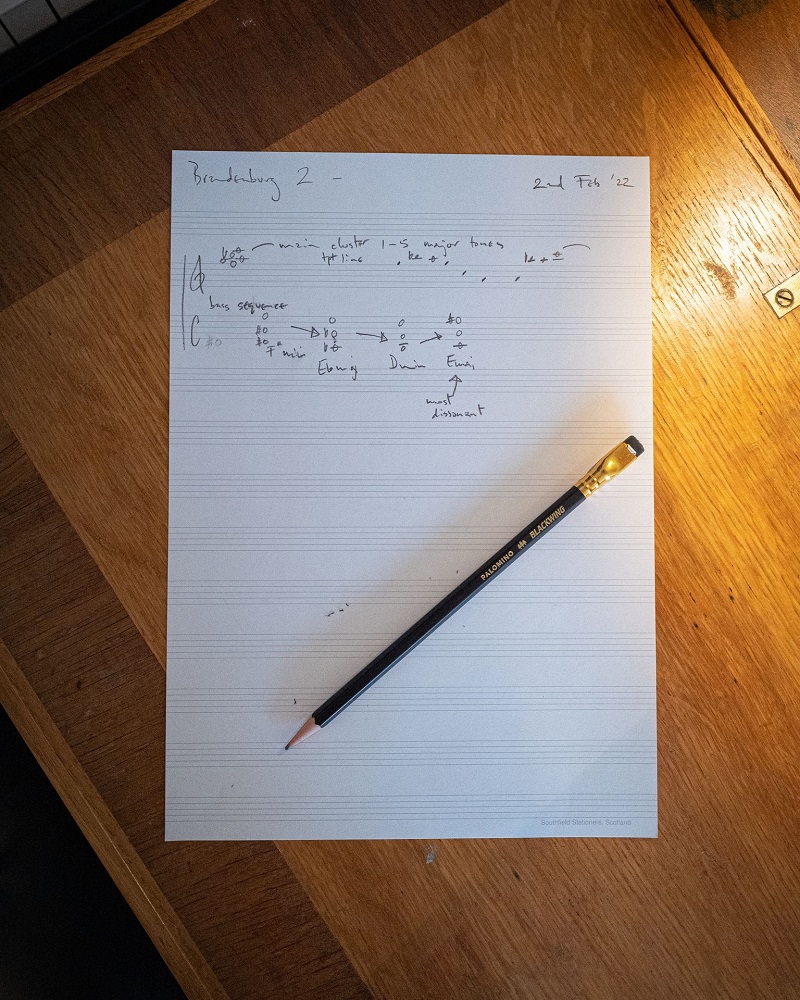

Part of the great joy and challenge of writing a new piece is that it is both a literally and figuratively blank piece of paper (when it comes to writing for film and TV, there is so much that is already given). In this case, I found myself creating a musical “building” on the page.

Part of the great joy and challenge of writing a new piece is that it is both a literally and figuratively blank piece of paper (when it comes to writing for film and TV, there is so much that is already given). In this case, I found myself creating a musical “building” on the page.

There's a 10-note theme that we hear right in bar one, which becomes nine, then eight, and counts down to just a single last note, before the underlying momentum of the piece kicks in. It then appears to count back up from one note to 10 notes over the rhythmic motion of the group, and already it feels like we’re in a series of reflecting surfaces, or facets of a jewel. After the trumpet solo, which felt to me like a lost image trapped right inside the diamond itself, the jewel turns again and we count our way back out into the light.

So although The Malling Diamond isn’t a story or a case to solve in the same way as in a TV drama, I hope there’s structure and form, and a journey that the players and listeners can go on. My own journey with the piece included some hidden gems. Like many of us, I’ve been working from home recently, and found a beautiful 1950s architect’s desk for my study, made of Yorkshire oak, on eBay (pictured below). I’ve been cleaning it up as I wrote the piece and drafted out some of the number patterns. I think in another life I would have liked to design buildings, as music and architecture have more in common than we may think.  One of my favourite places to visit in the whole of London is the music manuscript cabinet in the British Library. I firmly recommend it, if you’ve not been. In it you can see handwritten manuscripts from centuries ago, next to much more contemporary pieces. I always find it stunning how similar the process is, of putting pencil to paper, but how different the times we live in are. That’s what shines through this particular commission: so as fresh, committed performances of old works show them in a new light, so new works written for those same instruments tell us about the times we live in now.

One of my favourite places to visit in the whole of London is the music manuscript cabinet in the British Library. I firmly recommend it, if you’ve not been. In it you can see handwritten manuscripts from centuries ago, next to much more contemporary pieces. I always find it stunning how similar the process is, of putting pencil to paper, but how different the times we live in are. That’s what shines through this particular commission: so as fresh, committed performances of old works show them in a new light, so new works written for those same instruments tell us about the times we live in now.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

Add comment