Classical CDs: Snowy wastes, Alpine schleps and sand dunes | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Snowy wastes, Alpine schleps and sand dunes

Classical CDs: Snowy wastes, Alpine schleps and sand dunes

Big box bonanza: French song, seasonal transcriptions and 20th century orchestral music

Fauré: Complete Songs Cyrille Dubois (tenor), Tristan Raës (piano) (Aparté/ Palazzetto Bru Zane)

Fauré: Complete Songs Cyrille Dubois (tenor), Tristan Raës (piano) (Aparté/ Palazzetto Bru Zane)

Forget streaming. Go and buy albums. This 3-CD box set of Fauré songs by tenor Cyrille Dubois and pianist Tristan Raës comes to life when it is paired with its brilliantly put-together 140-page booklet, of essays and words and translations, making the whole enterprise worthwhile. The essays tell the story of the phases in Fauré’s songwriting clearly and thoughtfully. And if there’s a single unidiomatic translation or misprint lurking somewhere in the acres of text, I haven’t yet found it. What we are presented with is three discs and 103 songs. Graham Johnson’s Guildhall Research Study, Gabriel Fauré: The Songs and their Poets from 2009, lists a few more songs with more than one voice, but what we have here is pretty comprehensive. The long career of Fauré takes us through from his very first song from 1861, right up to the moonlit seascapes of L'Horizon Chimérique from 1921. The items are not ordered chronologically, but all the cycles are performed as units and each of the three discs has a well-thought-through programme.

The things I have enjoyed most about this set are the new discoveries. "Le Secret", Op. 23 No.3, from 1880, sets verse by Armand Silvestre, the poet from the Parnassian movement whom Fauré set more than any other. It’s an absolute gem. It has also been fascinating to explore the settings of Leconte de Lisle. Proust once wrote in a double-edged way that Leconte de Lisle had purged the French language of stupid metaphors... and replaced it with his own “bizarre” language. His unique poetry is a wonderful world to dip into again, and we are well served by both the cleverness of Fauré's settings and the clarity of Dubois's diction.

And then there are the more familiar high-spots like the five thematically linked Verlaine settings published as Cinq Mélodies "de Venise" from 1891. There are oddities too, like the rhetorical flourishes of "Hymne à Apollon", part of the French contribution to the Athens Olympics of 1896. Cyrille Dubois and Tristan Raës have worked as a duo for fifteen years. They know this repertoire thoroughly, and empathize with it totally. These are performances which follow dynamic markings to the letter. Dubois always opts for the line as written on the stave rather than any of the ossia’s which Fauré offers singers with a narrower vocal compass. These performances certainly serve as a reference. Whether they become a cornerstone of one’s listening will be a matter of choice. I am in awe of Tristan Raës’s pacing, I love the way this duo can conjure up a convincing mood for every song. But - and I am almost ashamed to admit it - I have one problem. It is Dubois’ pronunciation of the letter ‘r’. He takes the option to sing the guttural (phonetic symbol ⟨ʁ⟩), but his is a curious trilled consonant, almost like a personal contrivance, and the more I have listened the more intrusive I have found it. In a song like “Au Bord de l’Eau” the ‘r’, particularly after an open vowel (“voir” for example), sounds uncomfortably like a gargle. I do not necessarily expect any other listener to share this reservation. It needs saying in conclusion: Bru-Zane set very high standards, and this is a remarkable release.

Sebastian Scotney

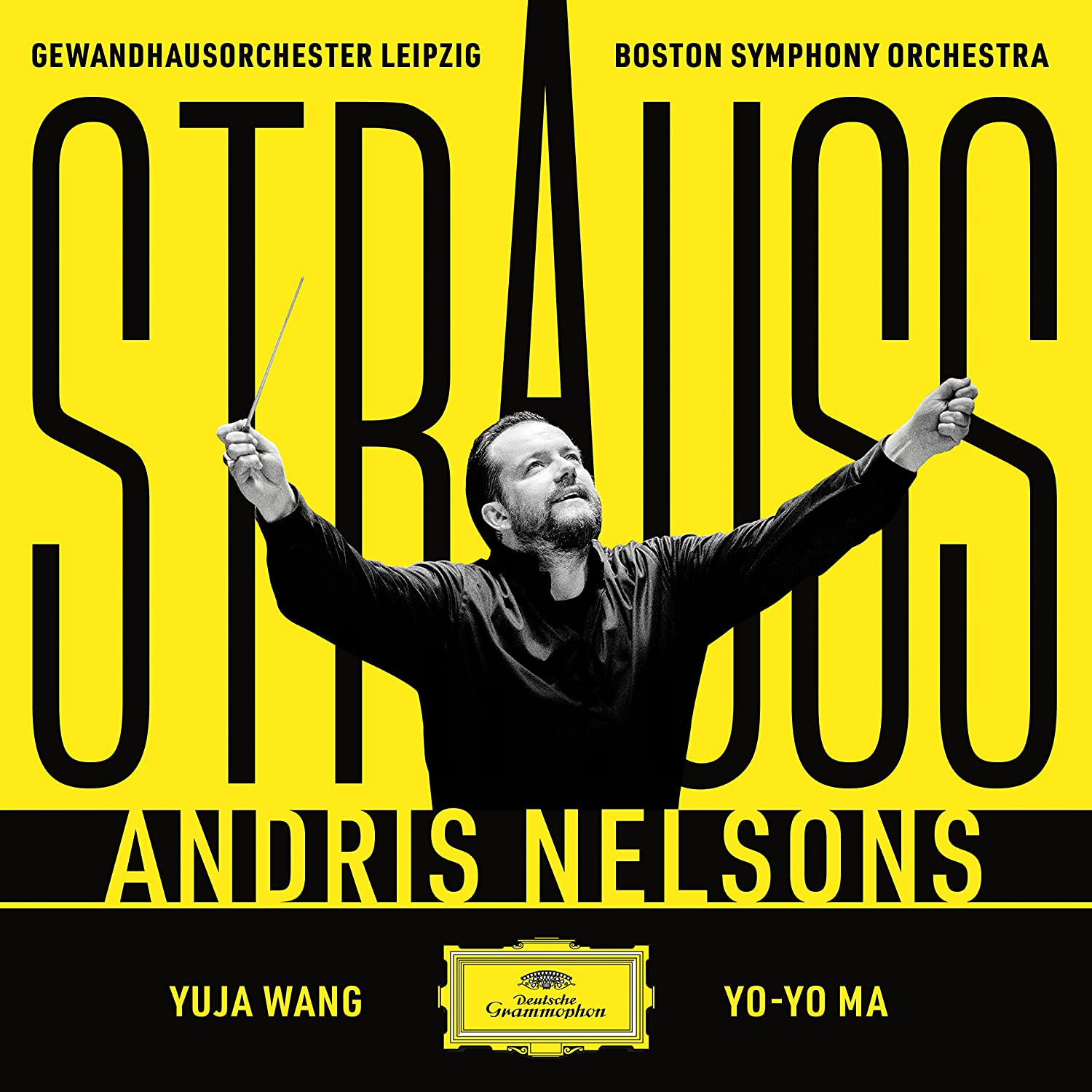

Andris Nelsons: Strauss Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Boston Symphony Orchestra, with Yuja Wang (piano and Yo-Yo Ma (cello) (DG)

Andris Nelsons: Strauss Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Boston Symphony Orchestra, with Yuja Wang (piano and Yo-Yo Ma (cello) (DG)

Strauss? All of it? Not quite, though all the big stuff is here. Orchestral duties are neatly split between Andris Nelsons’ two orchestras; each one supplies a trio of CDs, the seventh disc including the two ensembles combined to blast out the Festliches Präludium, 14 minutes of excruciating bombast for organ and huge orchestra. Fun to hear once, and Nelsons’ massed forces are clearly enjoying themselves, but it’s not something I’ll return to in a hurry. There are some superb performances here. Nelsons’ Boston Alpensinfonie is as good as his 2010 CBSO recording on Orfeo, the slow opening full of spooky detail. Nelsons’ arrival at the summit is terrific, and the storm sequence is a thriller. Winds and principal horn are magical in Strauss’s “Epilogue” before the crepuscular fade. I like this Boston version of Don Quixote too, Yo-Yo Ma and violist Steven Ansell nicely balanced, Nelsons and Ma handling Quixote’s disastrous duel and return to sanity with tenderness and compassion. Boston rarities include the Symphonic Fantasy from Die Frau ohne Schatten and the 4 Symphonic Interludes from Intermezzo, all beautifully played, plus the neglected Symphonia Domestica. I’ll stick my neck out and admit that this is a piece I still can’t get my head around, and not even the collective virtuosity of Nelsons’ Boston Symphony (listen to the horns’ stratospheric ascent in the “Finale”) could convince me. Tod und Verklärung is successful, with a splendid tam-tam stroke as the protagonist dies, Strauss’s debt to Tchaikovsky in the faster music clear.

The Gewandhausorchester’s Heldenleben features a suitably spiky set of critics and a fearless trumpet in the battle scene. The work’s second half can drag but Nelsons never lets the self-quotations feel indulgent, the hero’s retreat well-earned. This Also Sprach Zarathrustra doesn’t drag and features a telling contribution from violinist Sebastian Breuninger. And how good it is to hear the underrated Aus Italien dispatched with such affection. Don Juan falls a bit flat when stretched out to 20 minutes; Welser-Möst’s recent live Cleveland recording shows how it should be done. Yuja Wang has fun with the Burleske and there’s an expectedly thrilling account of the Tanz der Sieben Schleier from Salome. Metamorphosen boasts sumptuous, dusky string playing. Disc 7 includes a Boston reading of Till Eulenspiegel which needs a bit more oomph and wit, plus Leipzig performances of the Rosenkavalier suite and the flimsy Schlagoberswalzer. The hits are far more plentiful than the misses, and this bargain-priced, nicely packaged box set is worth acquiring. Completists should supplement it with Warner Classic’s budget-priced reissue of Rudolf Kempe’s 1970s Strauss Edition with the Staatskapelle Dresden. Kempe includes all the concertante works, and the analogue engineering still impresses.

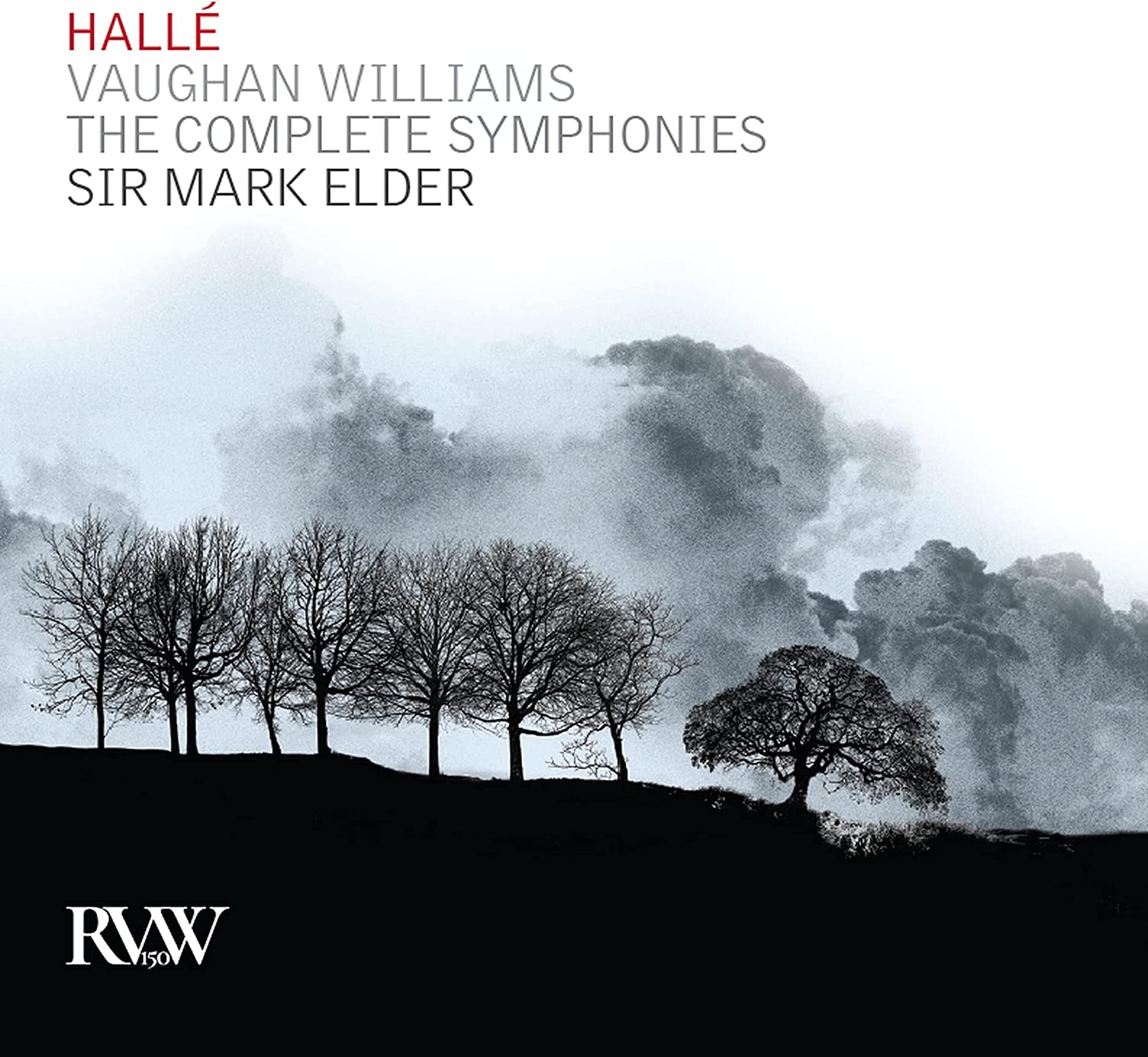

Vaughan Williams: The Complete Symphonies Hallé/Sir Mark Elder (Hallé)

Vaughan Williams: The Complete Symphonies Hallé/Sir Mark Elder (Hallé)

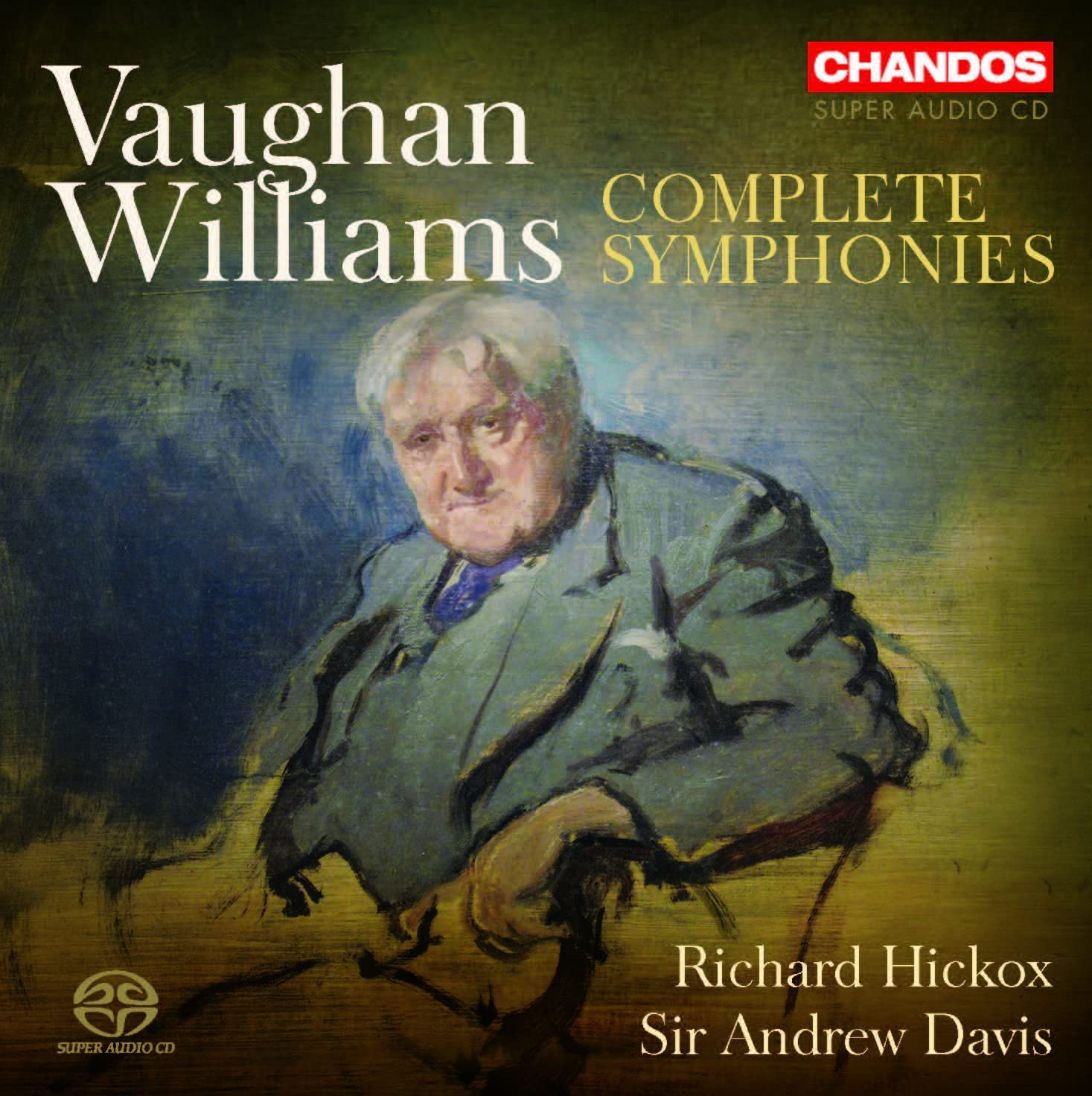

Vaughan Williams: Complete Symphonies London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox, Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Andrew Davis (Chandos)

There’s a hefty pile of Vaughan Williams CDs in my intray at present, which I’ll get to in a few weeks. As an appetiser, here’s a pair of symphony cycles, each repackaging discs which were previously issued separately. Sir Mark Elder’s Hallé box was recorded between 2010 and 2021. Symphonies 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 are taken from performances given in Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall; 3, 6 and 9 are studio recordings. Hickox began recording his cycle with the London Symphony Orchestra in 2000, mostly using the resonant acoustic of All Saints’ Church, Tooting. His unexpected death in 2008 left the set incomplete, Sir Andrew Davis and the Bergen Philharmonic later adding Symphonies 7 and 9.

Hickox ruffled feathers with his recording of No. 2, “A London Symphony”, the first to use Vaughan Williams’ original 1913 version. Lasting over an hour, it contains 15-20 minutes missing from the tauter original. Compare the versions side by side and the 1933 revision is undoubtedly the better work. But the 1913 score contains some wonderful music. Bernard Herrmann lamented the cuts made in the slow movement, complaining that Vaughan Williams had removed “some of the most original poetic moments in the entire symphony”, and even more striking are a mind-bogglingly beautiful additional trio section in the scherzo and an extended last movement epilogue. Handsomely played and ripely recorded, it’s a must-hear. Elder’s live reading of the revised version is perky and soulful but doesn’t efface memories of Barbirolli’s 1957 LP with the same orchestra, occasionally rough-edged but full of character. Both performances of the Sea Symphony are decent, though Hickox’s live Barbican account has much more sonic impact. Soloists in both London and Manchester are excellent (Susan Gritton and Gerald Finley for Hickox, Katherine Broderick and Roderick Williams for Elder), but the recorded balance tips things in Hickox’s favour. I prefer Elder’s more wistful take on the Pastoral Symphony, the slow movement’s elegiac brass solos beautifully played. Hickox’s heart doesn’t seem to be in it, though he makes amends with his version of No. 4. The London Symphony Orchestra’s playing is punchy, and there’s a thrilling mixture of Hollywood style gloss and raw anger. It’s great. Elder’s Hallé, distantly balanced by comparison, doesn’t have the same oomph

Fulsome LSO string playing in No. 5 makes Hickox’s performance one to cherish. Elder is more understated; both conductors are superb in the symphony’s extended coda. That serene stretch of music would have sounded like the summing up of a composer’s career when the work was premiered in 1943, making Vaughan Williams’ 1947 follow-up all the more surprising. Hickox’s ferocity is almost undermined by the boomy acoustic; Elder’s more distant balance has less impact but more of the details emerge. And, yes, the Sinfonia Antartica might be little more than a suite cobbled together from a film score, but it’s a brilliantly effective work when done well. A slightly slower tempo gives Elder’s first movement a bit more gravitas than Sir Andrew Davis in Bergen. Both conductors excel in the central “Landscape”, Davis’s organ more startling. The Hallé gave the first performance of the Sinfonia Antartica in 1953; one of the orchestra’s trumpet players later told me that Symphony No. 8, dedicated to Barbirolli, couldn’t help feeling underwhelming by comparison. Nonsense. No. 8, short, colourful and quirky, gets better and better with repeated listens. Hickox’s tuned percussion overwhelm in the clangourous last movement, which suits me; Elder is more reserved, the drier acoustic of the BBC’s Salford studio allowing us to hear everything. Davis is swifter in the unsettling Symphony No. 9, Elder’s broader tempi making the work feel more valedictory. Chandos’s box fills six discs rather than Elder’s five and includes some enticing spoken word extras: Vaughan Williams reminiscing about his life and career, plus contributions from Boult, Barbirolli and the composer’s widow Ursula. You’d be happy with either set, and the late Michael Kennedy’s eloquent sleeve notes are common to both.

Fulsome LSO string playing in No. 5 makes Hickox’s performance one to cherish. Elder is more understated; both conductors are superb in the symphony’s extended coda. That serene stretch of music would have sounded like the summing up of a composer’s career when the work was premiered in 1943, making Vaughan Williams’ 1947 follow-up all the more surprising. Hickox’s ferocity is almost undermined by the boomy acoustic; Elder’s more distant balance has less impact but more of the details emerge. And, yes, the Sinfonia Antartica might be little more than a suite cobbled together from a film score, but it’s a brilliantly effective work when done well. A slightly slower tempo gives Elder’s first movement a bit more gravitas than Sir Andrew Davis in Bergen. Both conductors excel in the central “Landscape”, Davis’s organ more startling. The Hallé gave the first performance of the Sinfonia Antartica in 1953; one of the orchestra’s trumpet players later told me that Symphony No. 8, dedicated to Barbirolli, couldn’t help feeling underwhelming by comparison. Nonsense. No. 8, short, colourful and quirky, gets better and better with repeated listens. Hickox’s tuned percussion overwhelm in the clangourous last movement, which suits me; Elder is more reserved, the drier acoustic of the BBC’s Salford studio allowing us to hear everything. Davis is swifter in the unsettling Symphony No. 9, Elder’s broader tempi making the work feel more valedictory. Chandos’s box fills six discs rather than Elder’s five and includes some enticing spoken word extras: Vaughan Williams reminiscing about his life and career, plus contributions from Boult, Barbirolli and the composer’s widow Ursula. You’d be happy with either set, and the late Michael Kennedy’s eloquent sleeve notes are common to both.

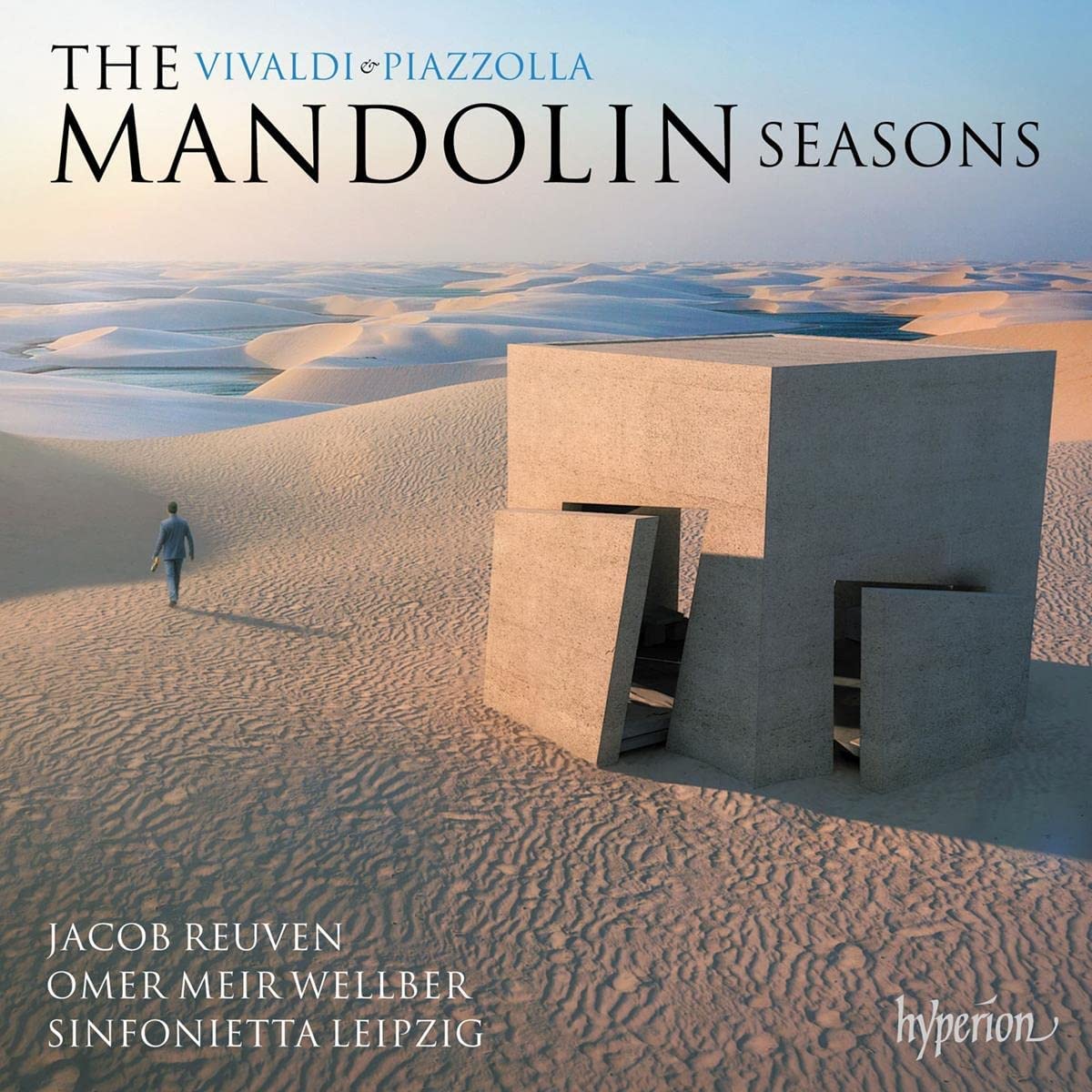

Vivaldi & Piazzolla: The Mandolin Seasons Jacob Reuven (mandolin), Omer Meir Wellber (accordion/harpsichord, conductor), Sinfonietta Leipzig (Hyperion)

Vivaldi & Piazzolla: The Mandolin Seasons Jacob Reuven (mandolin), Omer Meir Wellber (accordion/harpsichord, conductor), Sinfonietta Leipzig (Hyperion)

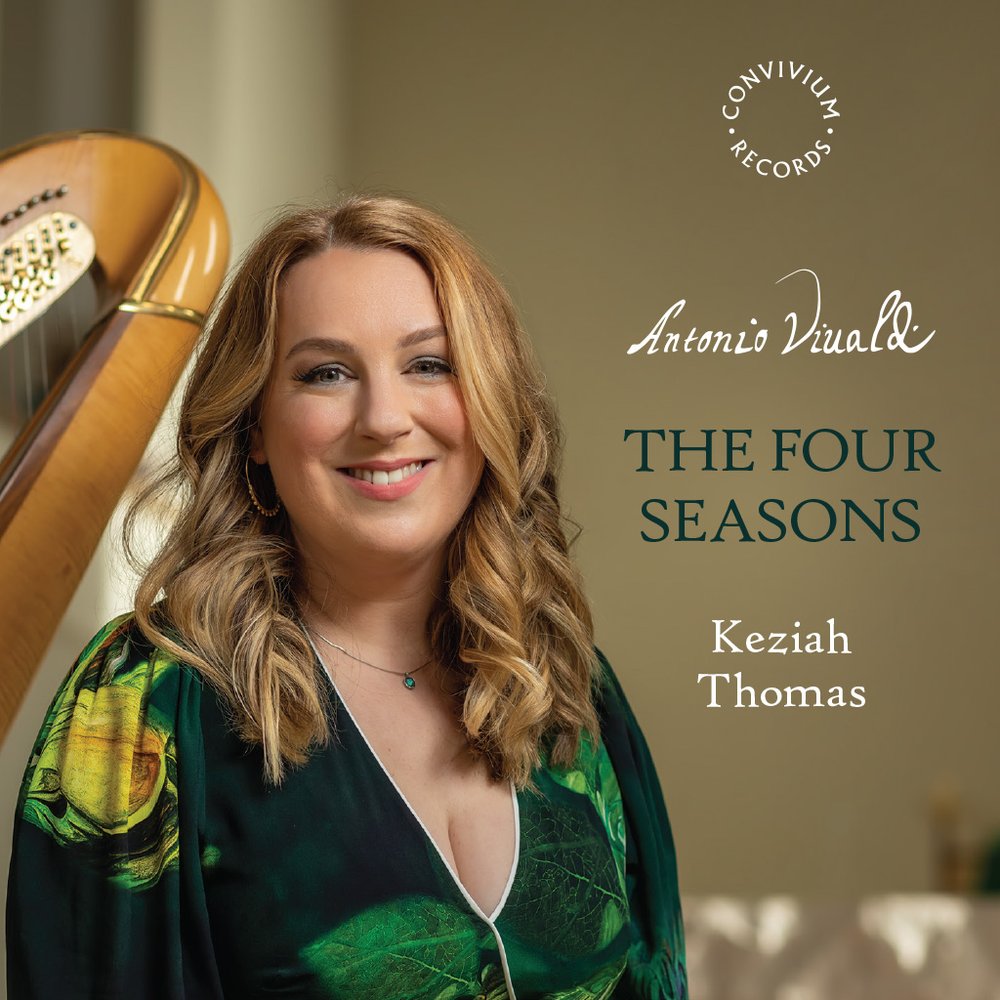

Vivaldi: The Four Seasons, arranged for harp by Keziah Thomas (Convivium Records)

Two successful reinventions of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons have kept me entertained in recent months. That from Israeli mandolinist Jacob Reuven and his childhood friend, conductor/accordionist Omer Meir Welber (the BBC Philharmonic’s Chief Conductor), intersperses mandolin versions of the original with an adaptation Leonid Desyatnikov’s arrangement of Astor Piazzolla’s Las cuatro estaciones porteñas. Wellber, on accordion and harpsichord, doubles as continuo player and occasional soloist. The effect us striking, at times “transporting the listener from 18th century Venice to the sand dunes of the Middle East”. Vivaldi’s mandolin concertos don’t place huge demands on the soloist and Reuven’s dexterity when tackling a violin part is astonishing. There’s a good clip of him playing “Summer” on YouTube, his right hand almost a blur. Wellber’s pedal notes are suitably menacing at the start of “Winter”, and he throw in some nifty trills in the first movement of “Autumn”. It’s beguiling stuff, the mandolin versions of the Piazzolla numbers equally convincing. Reuven’s flurries of notes at the start of “Summer in Buenos Aires” will make you laugh out loud. A lovely disc, neatly accompanied by members of the Gewandhausorchester (see above).

Keziah Thomas’s harp transcription is beautifully played. Having just one player allows Thomas a degree of rhythmic flexibility that feels exactly right; numbers like the slow movement of “Spring” are delicious. I like the moments where everything feels stripped to its essentials; the hushed middle section of “Summer” really works, the harp’s lowest notes chiming out like bells. And check out how Thomas reinvents the opening of “Winter”, an unlikely mixture of seductive warmth and bitter cold.

Keziah Thomas’s harp transcription is beautifully played. Having just one player allows Thomas a degree of rhythmic flexibility that feels exactly right; numbers like the slow movement of “Spring” are delicious. I like the moments where everything feels stripped to its essentials; the hushed middle section of “Summer” really works, the harp’s lowest notes chiming out like bells. And check out how Thomas reinvents the opening of “Winter”, an unlikely mixture of seductive warmth and bitter cold.

Solitude Joo Yeon Sir (violin) (Rubicon)

Solitude Joo Yeon Sir (violin) (Rubicon)

CDs made during lockdown keep on appearing, and violinist Joo Yeon Sir’s Solitude is a decent one. Has someone compiled a chart showing an increase in solo recital discs, presumably matched with a steep drop in orchestral releases? One upside is encountering repertoire out of one’s comfort zone; I never previously imagined that I’d enjoy solo string music so much. Sir’s version of Ysaÿe’s Sonata No. 6 is terrific, a performance which draws you in with a wink and a grin. Ysaÿe sonatas can too often sound like a gymnastics routine in musical form – Sir brings out the music’s humour. A pair of Paganini Caprices are approached in a similar way; No. 10 ‘s dance rhythms are stressed, and there’s sweetness as well as sparks in No. 24. Biber’s Passacaglia in G minor is cool but incredibly assured, and it’s difficult not to smile at the G major close. Kreisler’s Recitativo and Scherzo-Caprice, composed for Ysaÿe, is superb here, with unsettling harmonics in the introduction and a flamboyant second half.

Roxanna Panufnuik’s exhilarating Hora Bessarabia takes inspiration from Bulgarian folk rhythms, Sir signalling the close with a foot stamp. Fazil Say’s fiendish Cleopatra makes brilliant use of Arabic dance rhythms. Laura Snowden’s Through the Fog, composed for Sir, is a poignant, subdued meditation. Sir’s own My Dear Bessie is a musical response to the epistolary romance between Chris Barker and Bessie Moore during World War 2, their evolving relationship described in scores of love letters between the pair. There’s “longing, fear and hope”, the pairs’ forced separation alarmingly pertinent during recent lockdowns. Listen carefully for a hint of Vera Lynn’s “We’ll Meet Again.” A moving album, beautifully recorded.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Add comment