William Kentridge, Royal Academy review - from art to theatre, and back again | reviews, news & interviews

William Kentridge, Royal Academy review - from art to theatre, and back again

William Kentridge, Royal Academy review - from art to theatre, and back again

The past is hideous, the future an unknown entity in the varied forms of the artist's work

South African artist William Kentridge appears on video in his studio, twice. On the right he sits scribbling, waiting for an idea to surface. Meanwhile his alter ego stands impatiently by, trying to peek at his other half’s notes and, desperate for enlightenment, even reads a recipe out loud. The artist, it seems, doesn’t have a clue; he is as much in the dark as everyone else. A Lesson in Lethargy, 2010 offers a brief moment of humour in this relentlessly dark exhibition.

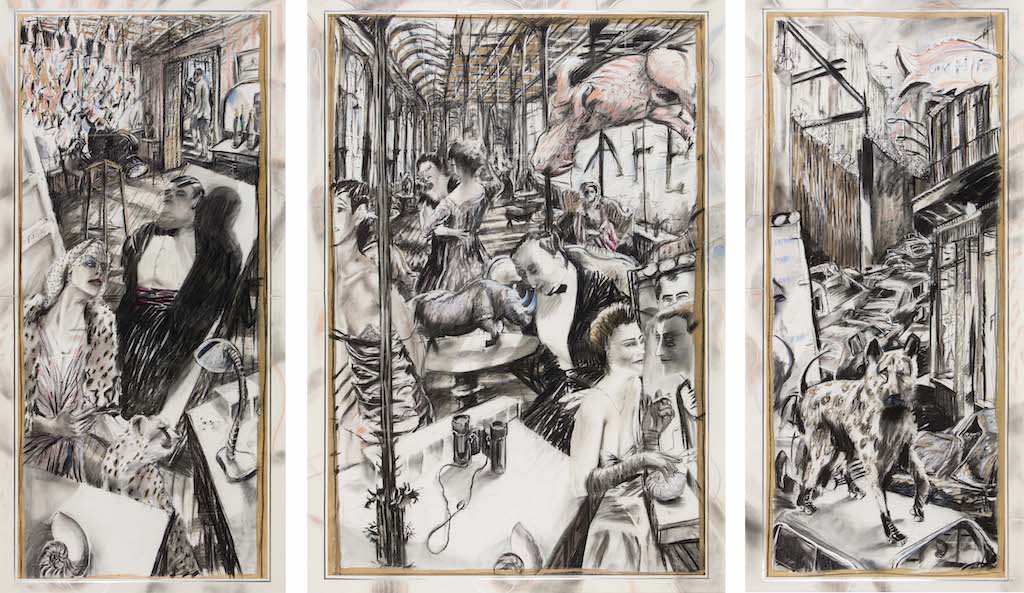

Born in Johannesburg in 1955, Kentridge grew up under apartheid and the large charcoal drawings that open the Royal Academy show allude to the racism, brutality and corruption of that hideous regime. You might be forgiven for thinking they were by Max Beckmann, Otto Dix or George Grosz who, after the First World War, used biting satire to castigate the politicians and top brass they held responsible for the conflict and the fat cats who profiteered from it. In The Conservationists' Ball, 1985 (pictured below), Kentridge similarly caricatures the self-serving elite and adds wild animals such as jackals, hyenas and rhinos to the mix as symbols of the greed and corruption infecting society.

Four years later he began translating his drawings into animated films. Instead of making a separate image for each frame, he reworks the same drawing over and over – adding, modifying and erasing the charcoal so that each shot bears ghostly traces of all those before. You are constantly reminded of the artist’s hand – it’s almost as though you were looking over his shoulder while he sketches – and as the traces, smears and smudges build up, the images get murkier and less distinct. Many find his technique beguiling, but for me it’s the visual equivalent of trudging through mud; freighted with its own past, each drawing seems to get weightier and denser. Five of his 11 films fill one room. Johannesburg Second Greatest City After Paris, 1989 features a pin-striped property tycoon, Soko Eckstein. Having bought up half Johannesburg, he screams down telephones making deals that will earn him a bomb but cause hardship to thousands. Stuffing his face with delicacies, he lobs the leftovers at the dispossessed who march towards him in a pitiful throng. Meanwhile, his bored wife indulges in an affair with Felix Teitelbaum, whose lewd imaginings are detailed on screen and who bears an uncanny resemblance to the artist.

Five of his 11 films fill one room. Johannesburg Second Greatest City After Paris, 1989 features a pin-striped property tycoon, Soko Eckstein. Having bought up half Johannesburg, he screams down telephones making deals that will earn him a bomb but cause hardship to thousands. Stuffing his face with delicacies, he lobs the leftovers at the dispossessed who march towards him in a pitiful throng. Meanwhile, his bored wife indulges in an affair with Felix Teitelbaum, whose lewd imaginings are detailed on screen and who bears an uncanny resemblance to the artist.

Scenes relentlessly appear, morph and disappear; everything changes, but nothing is resolved. There’s no respite from the darkness. In City Deep, 2020 Eckstein visits an art gallery; while contemplating the pictures, the ground opens up beneath his feet, the building starts to crumble and the paintings turn to dust and cascade off the walls. Art, it seems, offers no safe haven; it is as vulnerable to devastation as everything else.

Don’t be fooled by the apparent charm of Black Box/Chambre Noire, 2005. Projected onto automated puppets that cavort inside a miniature theatre, the film explores the genocide of the Herero and Nama people perpetrated in Namibia by German colonialists in 1908. The switch to film from the murky confines of charcoal is a relief, but the subject matter is no less grim.

Kentridge’s propensity for layering images finally comes into its own in Notes Towards a Model Opera, 2015. The three-screen film projection parodies the operas created by Chairman Mao’s wife, Yiang Qing, which, with names like Red Detachment of Women, glorify revolutionary struggle and communist ideals.

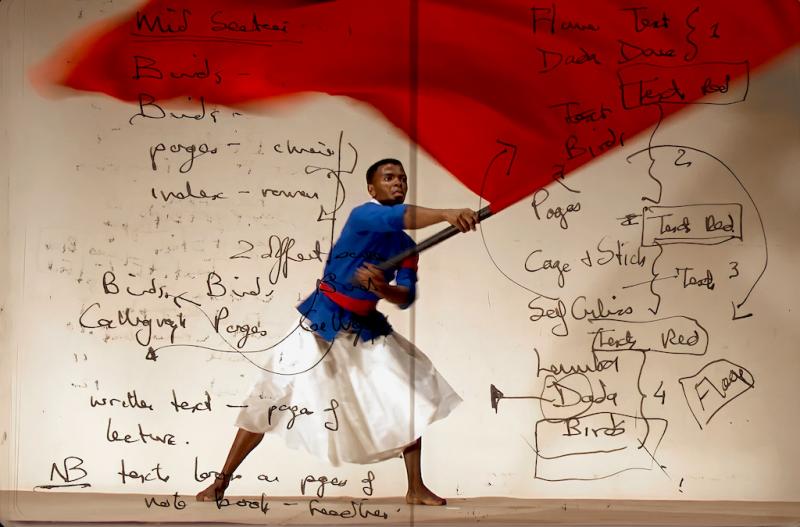

Wearing military uniform and brandishing a gun, a black ballerina pirouettes in endless circles. Carrying placards bearing meaningless maxims such as Pause and Use the Wind, another dancer gyrates to the pounding of African drums over pages of a giant atlas. A man twirls a red flag in front of pages from the artist’s notebook detailing ideas for the film (main picture). Birds, Birds, for instance, commemorates the sparrows misguidedly killed in a bid to boost crop yields in China; next, we see them flying across the pages of accounting ledgers.

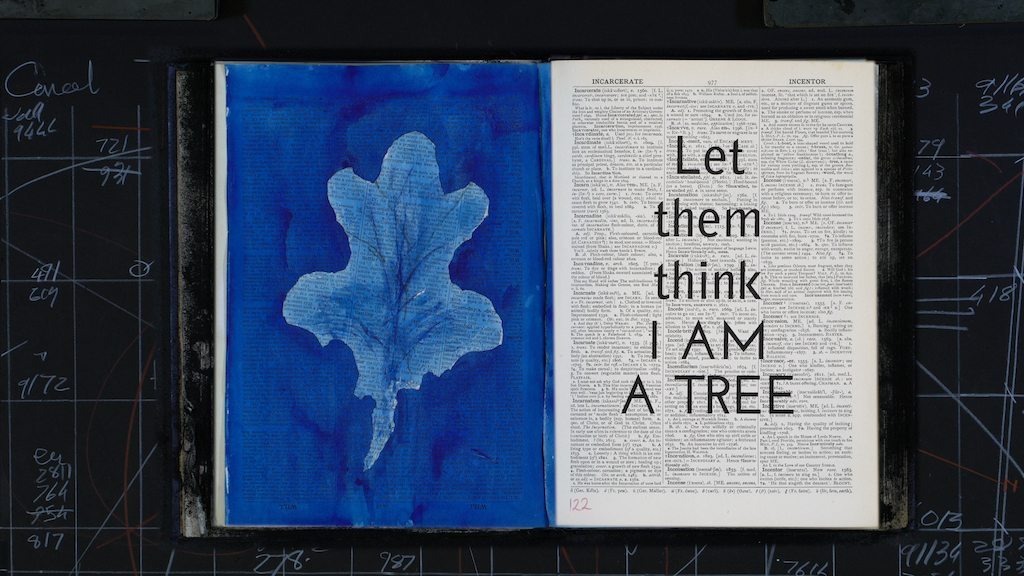

And suddenly the constant layering begins to make sense. Instead of a charcoal drawing morphing into its successor, now several images can coexist and through their juxtaposition create a wealth of ideas and associations. And instead of dragging the present down, the past is brought into lively dialogue with it. The final installation is a reprise of Waiting for the Sibyl, 2019, a chamber opera (pictured above: detail) featuring music by Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd. We are at the entrance to Hades where people come to question the Sibyl about their fate. She writes her answers on leaves, but the wind blows them about so no-one can be sure if they have the right reply. As people scrabble about for answers, gnomic messages appear on a large screen. “Where shall we put our hope?”, “You have nowhere to go” and “Your turn is next” address the uncertainties of life in general and our present moment in particular, with a poetry that avoids the dreary fatalism implicit in the charcoal animations.

The final installation is a reprise of Waiting for the Sibyl, 2019, a chamber opera (pictured above: detail) featuring music by Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd. We are at the entrance to Hades where people come to question the Sibyl about their fate. She writes her answers on leaves, but the wind blows them about so no-one can be sure if they have the right reply. As people scrabble about for answers, gnomic messages appear on a large screen. “Where shall we put our hope?”, “You have nowhere to go” and “Your turn is next” address the uncertainties of life in general and our present moment in particular, with a poetry that avoids the dreary fatalism implicit in the charcoal animations.

In the early 1980s Kentridge studied at the Jacques Lecoq theatre school in Paris and for many years he worked in Johannesburg as an actor and director. His more recent return to the stage feels like a homecoming, in which his many skills can at last be used to complement one another.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment