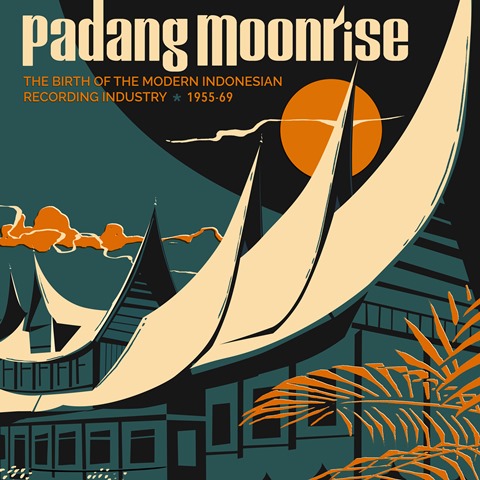

Music Reissues Weekly: Padang Moonrise - The Birth of the Modern Indonesian Recording Industry | reviews, news & interviews

Music Reissues Weekly: Padang Moonrise - The Birth of the Modern Indonesian Recording Industry

Music Reissues Weekly: Padang Moonrise - The Birth of the Modern Indonesian Recording Industry

Eye-opening compilation where knowing the context is essential

“Ka Huma” by Ivo Nilakreshna sounds as if a jazz band was taking on rock ’n’ roll. There’s a swing and sway, busy rhythm guitar and a lead female voice singing a yearning melody. An instrument which seems to vibes is in there. But there’s more than the familiar elements. Most of the influences are unrecognisable.

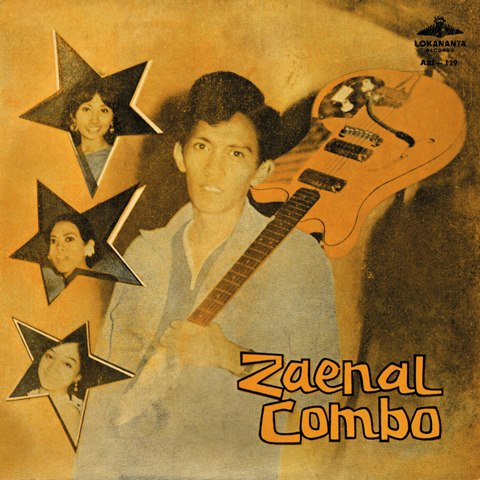

Zaenal Combo’s “Tandung Tjina” is an rocking instrumental with a comparable otherness. There’s a kinship with California surf band The Pyramids’s “Penetration” but, again, the primary building blocks are out of reach. Both tracks appear to have sprung from an unfamiliar well.

And so it proves. “Ka Huma” and “Tandung Tjina” are on either side of seven-inch single coming with the vinyl version of the double album Padang Moonrise: The Birth of the Modern Indonesian Recording Industry (1955-69) – all the tracks are on the CD configuration too. Based in Jakarta, Zaenal Combo were a vehicle for the arranger, bandleader, composer and guitarist, Zaenal Arifin – his bands, says the accompanying essay, “played modernized traditional songs from across the Indonesian archipelago.”

And so it proves. “Ka Huma” and “Tandung Tjina” are on either side of seven-inch single coming with the vinyl version of the double album Padang Moonrise: The Birth of the Modern Indonesian Recording Industry (1955-69) – all the tracks are on the CD configuration too. Based in Jakarta, Zaenal Combo were a vehicle for the arranger, bandleader, composer and guitarist, Zaenal Arifin – his bands, says the accompanying essay, “played modernized traditional songs from across the Indonesian archipelago.”

As the Indonesian archipelago includes around 17,000 islands, covers close to three-quarters of a million square miles, incorporates different groupings of peoples and has a substantial amount of languages, getting a grip on one aspect of the region’s story has to be difficult. However, Padang Moonrise’s full title makes explicit the focus on the emergence of a pop music and the infrastructure which supported it. Reading the lengthy essay by Andrew N. Weintraub is necessary.

Professor Weintraub is based at the University of Pittsburgh. “Indonesia is a major focus of my research, particularly the musical, narrative, and theatrical practices of Sundanese people in West Java,” says his on-line biography. “In 2003, I began to explore a genre of Indonesian national popular music called dangdut.” His lengthy publication list includes the book Dangdut Stories. He also leads the band Dangdut Cowboys, who have played Indonesia. Padang Moonrise has to be a sharp collection.

What’s heard is – assumedly for most potential purchasers – previously unknown: contextually and musically. The 27 tracks are about pop, and the creation of a pop music from scratch. Weintraub says “during the regime of first President Sukarno (1945-1967), popular music [in the post-independence period] opened a space for multiple definitions of what the nation was and could be. Under these new historical and material conditions, Indonesians worked across geographical, ethnic, and linguistic boundaries, and created innovative forms of popular music and new forms of identity.” (pictured left, Ivo Nilakreshna)

What’s heard is – assumedly for most potential purchasers – previously unknown: contextually and musically. The 27 tracks are about pop, and the creation of a pop music from scratch. Weintraub says “during the regime of first President Sukarno (1945-1967), popular music [in the post-independence period] opened a space for multiple definitions of what the nation was and could be. Under these new historical and material conditions, Indonesians worked across geographical, ethnic, and linguistic boundaries, and created innovative forms of popular music and new forms of identity.” (pictured left, Ivo Nilakreshna)

“The modern Indonesian recording industry was born in the capital city of Jakarta in the early 1950s,” he continues. “A wide variety of genres includ[ed] Indonesian jazz and pop, Hawaiian, kroncong string-band music, Islamic-inspired qasidah and gambus, art music (seriosa), and regional popular music (lagu daerah, including orkes Melayu) with heavy Western and Latin influences.”

Multiple flavours of this pop music crop up on Padang Moonrise. “Bulan Dagoan” by Orkes Teruna Ria is the opening track. Slow and drifting, it seems melancholy. In another world, it could soundtrack a reflective moment in an Aki Kaurismaki film. An Orkes Teruna Ria album sleeve said of the band “maybe it’s the way they dress: bright colors, the cut of their clothes and exotic-looking pants, complete with fine bamboo hats and bare feet. It’s as if they came from the warm-blooded continent of Latin America. All of that is fitting for the kind of music they play: the hot Latin rhythms now popular among our country’s people. Even the name of the group describes what they do: the Cuban Rhythms of Teruna Ria.”

Zaenal Combo’s “Seruling” is spacey, and could have been a Joe Meek production. Orkes Kelana Ria’s “Sojang” is jazzy, in the early John Barry soundtrack way. Orkes Tropicana’s "Pantjaran Kasih" is a form of pop jazz. Some of Padang Moonrise bears the influence of The Shadows and The Ventures. Ahai Dara’s “Mus D.S.” has shades of The Beatles. But despite what’s evoked, nothing sounds like what might be feeding into the music – influences are transformed.

Zaenal Combo’s “Seruling” is spacey, and could have been a Joe Meek production. Orkes Kelana Ria’s “Sojang” is jazzy, in the early John Barry soundtrack way. Orkes Tropicana’s "Pantjaran Kasih" is a form of pop jazz. Some of Padang Moonrise bears the influence of The Shadows and The Ventures. Ahai Dara’s “Mus D.S.” has shades of The Beatles. But despite what’s evoked, nothing sounds like what might be feeding into the music – influences are transformed.

Locally, balances had to be struck. Creating the music wasn’t necessarily straightforward. Weintraub says “Sukarno believed that Western pop and rock ’n’ roll would distract youth from fighting against Western imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism. Sukarno portrayed the spread of Western popular culture, especially music and dance, as an unwarranted, disruptive, and dangerous symbol of cultural imperialism. In his Independence Day speech on 17 August 1959, Sukarno used the term “ngak-ngik-ngok” (“noisy, irritating, and grating”) to refer to rock ’n’ roll, cha-cha, and other forms of music and dance that made people act “crazy” (gila-gilaan). In 1963, Sukarno banned the sounds and movements associated with these forms because they allegedly threatened to steer Indonesian youth away from their true identity and duties as national citizens.”

Discovering the context for what’s heard is essential – these 27 tracks were recorded when the state had very particular views on what music should or should not be. Even so, it was possible to sidestep dogma. Padang Moonrise: The Birth of the Modern Indonesian Recording Industry (1955-69) is about more than the music.

- Next week: All Killer No Filler (1977-2001) - punky New Yorkers The Senders are compiled

- More reissue reviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

10 Questions for musician Michael Gira

Experimental rock titan on never retiring, meeting his idols and Swans’ new album

10 Questions for musician Michael Gira

Experimental rock titan on never retiring, meeting his idols and Swans’ new album

Album: Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Garbage plays it safe with their latest album

Album: Garbage - Let All That We Imagine Be The Light

Garbage plays it safe with their latest album

Album: Sally Shapiro - Ready to Live a Lie

Dance music-inspired Swedish pop which lacks the necessary vital spark

Album: Sally Shapiro - Ready to Live a Lie

Dance music-inspired Swedish pop which lacks the necessary vital spark

theartsdesk on Vinyl 90: Small Faces, ESKA, Luvcat, Dope Lemon, Celia Cruz, Monolake and more

The most monstrously huge regular record reviews in the universe

theartsdesk on Vinyl 90: Small Faces, ESKA, Luvcat, Dope Lemon, Celia Cruz, Monolake and more

The most monstrously huge regular record reviews in the universe

Album: Anna Lapwood - Firedove

Broad repertoire and a strong concept

Album: Anna Lapwood - Firedove

Broad repertoire and a strong concept

Music Reissues Weekly: Johnnie Taylor - Who's Making Love The Stax Singles 1966-1970

Proof there’s more to the soul stylist than the first big hit

Music Reissues Weekly: Johnnie Taylor - Who's Making Love The Stax Singles 1966-1970

Proof there’s more to the soul stylist than the first big hit

Album: Morcheeba - Escape the Chaos

More of the same from the trip hop perennials but delivered with tunes and ease

Album: Morcheeba - Escape the Chaos

More of the same from the trip hop perennials but delivered with tunes and ease

Album: Ammar 808 - Club Tounsi

Tunisian country roots meet urban tech

Album: Ammar 808 - Club Tounsi

Tunisian country roots meet urban tech

Album: Sports Team - Boys These Days

Genial guitar pop that leans into poshness, boasts smart lyrics, but lacks musical bite

Album: Sports Team - Boys These Days

Genial guitar pop that leans into poshness, boasts smart lyrics, but lacks musical bite

Pixies, O2 Academy, Birmingham review - indie veterans pack the house

Black Francis and his crew blow the crowd up with tunes old and new

Pixies, O2 Academy, Birmingham review - indie veterans pack the house

Black Francis and his crew blow the crowd up with tunes old and new

Album: Stereolab - Instant Holograms on Metal Film

Picking up their never-ending, archly peculiar groove, after 15 years

Album: Stereolab - Instant Holograms on Metal Film

Picking up their never-ending, archly peculiar groove, after 15 years

The Great Escape Festival 2025, Brighton review - a feast of music from across the world

Hitting Saturday shows by deBasement, Dog Race, Chloe Leigh, Oh Dirty Fingers & more

The Great Escape Festival 2025, Brighton review - a feast of music from across the world

Hitting Saturday shows by deBasement, Dog Race, Chloe Leigh, Oh Dirty Fingers & more

Add comment